A place for us

Anthology features writers seeking a better world

Anthology features writers seeking a better world

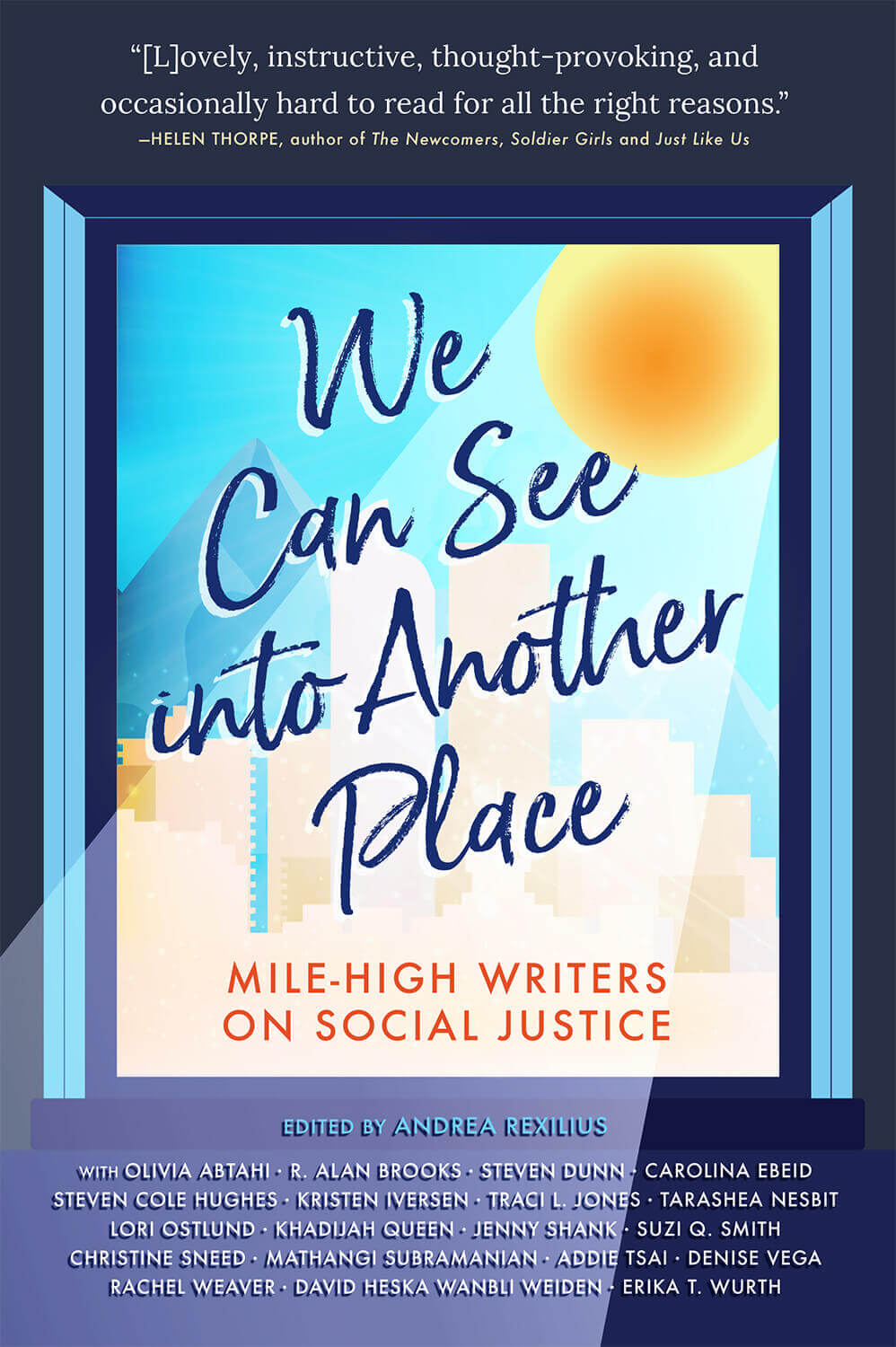

We Can See Into Another Place, a rich multi-genre anthology of work by Denver-based writers and faculty from the Mile-High MFA in Creative Writing Program, examines the purpose of writers in troubled times, “allowing [the] future to be hopeful, full or possibility, while also rooted in uncertainty.” This requires “the kind of fearlessness writers are deeply capable of performing,” says editor Andrea Rexilius in the Introduction.

Andrea Rexilius

In “Other People’s Mistakes,” Mathangi Subramanian’s searing, second-person story, we are literally taken to another place. “The clinic Alma sends you to is really just the back room of a 7-Eleven across the street from the Thai restaurant where Raj was supposed to propose,” it begins. That opening sentence blossoms like a multifaceted diamond, with cuts pertaining to race, class, gender and ethnicity. Alma means “soul” in Spanish; a corporate American mini-market with rafts of cheap stuff serves as a backdrop for both literal and metaphorical extermination of life; cuisine inspired by Thailand plays a minor part; and an Indian-American man thought to be considering marriage doesn’t quite come through as expected. High hopes, stupid decisions, crashed dreams and ultimately heroic truth telling and decision making are on display here, by a young woman who prioritizes her own existence rather than getting swept up in parental, legal and internalized forces. To say more would spoil the tale, which swiftly and beautifully accomplishes more in its 14 short pages than do some entire books.

Suzi Q. Smith, for her impressive part, operates somewhat sculpturally with words, disrupting traditional reading habits such as top to bottom and left to right on the page. This rings particularly true of “Square Dancing,” her evocative one page, four-by-four grid of rectangles peppered with text. These 16 shapes create a complex matrix of mundane social realities that inform one another through simple sentences that describe pedagogy, caretaking and customs, relating such facts as “A square is a plane figure with four equal sides and four right angles.” This mundane, well-known fact sits cheek by jowl with “Ms. Brown decided we needed to square dance and maybe she was right.” Woven right in is “When my grandfather raised his fist to my grandmother, she would pretend to pass out. He would rush to her aid, apologizing all the way (as if choreographed).” Likes, dislikes, doing and/or pretending to do things, instructions and disobedience feed into and off one another holding significant tension and several ways to get trapped. Nothing much more than a square dance happens. Meanwhile, quite a lot transpires mentally and spiritually, heightening the drama of people figuring out how, where, when, with whom and why to move across a dance floor.

Award-winning author and enrolled citizen of the Sicangu Lakota Nation, David Heska Wanbli Weiden,  describes himself as a “middle-aged professor of Native American Studies” in his first-person recollection of relocation camps where Native American children, including his grandmother, were taken for the cruel purpose of debriding them of Native culture without outright killing them. His grandmother, however,whose final residence was a small shack with no running water and no electricity, had fond recollections of the colonies that separated families and destroyed the culture her grandson has dedicated his life to learning and disseminating. Whether the grandmother lied to others, lied to herself or actually enjoyed growing up without her family or culture remains poignantly impossible to ascertain. Heska Wanbli Weiden’s rage, compassion and desire for comprehension work in tandem through this story, which looks at a series of events through multiple critical angles, all pointedly culminating in the extraordinary cruelty of exterminating Native American reality.

describes himself as a “middle-aged professor of Native American Studies” in his first-person recollection of relocation camps where Native American children, including his grandmother, were taken for the cruel purpose of debriding them of Native culture without outright killing them. His grandmother, however,whose final residence was a small shack with no running water and no electricity, had fond recollections of the colonies that separated families and destroyed the culture her grandson has dedicated his life to learning and disseminating. Whether the grandmother lied to others, lied to herself or actually enjoyed growing up without her family or culture remains poignantly impossible to ascertain. Heska Wanbli Weiden’s rage, compassion and desire for comprehension work in tandem through this story, which looks at a series of events through multiple critical angles, all pointedly culminating in the extraordinary cruelty of exterminating Native American reality.

On the subject of language, Tarashea Nesbit writes of learning she lived in Ohio “flyover” country unimportant to coastal U.S. cities, where she submitted a poem for a school poetry workshop that included the line “The floor needs swept.” This prompted the workshop instructor to ask her to “fix” it by inserting the words “to be.” Unwilling to alter the perfectly comprehensible line to fit a way of speaking that differed from the way her mom, dad, brothers, sisters, cousins, uncles and grandparents spoke, Nesbit opted to keep it the way she’d written it. Having grown into her own career as a writer outside of Ohio, and having come back with a husband and daughter, and having learned to consider the difference between uttering “soda” or “pop” when speaking of a carbonated beverage, Nesbit triumphantly and warmly ends her contribution by describing the time her daughter, fully understanding where the words “to be” might “belong” in a sentence, says of her own accord, “Mom, my dress needs washed.”

An odd but endearing series of questions fills pages left mostly blank near the end of We Can See into Another Place, offering the reader an invitation to fill in space and become part of the community established by the book. For example: “How does reading and/or writing help you get through ‘the dark times?’” Future writers are asked to “re-imagine” the future relative to social justice. This points to what We Can See into Another Place accomplishes quite well: allowing writers to explore and explain exactly where they are, offering readers a poignant view in, demonstrating that none of it remotely qualifies as stagnant.

Click here for more from Sarah Valdez.