From the archive to the page

Robert Harvey’s narrative account of Japanese Americans interned at Colorado’s Amache camp is revised and redistributed in new third edition

Robert Harvey’s narrative account of Japanese Americans interned at Colorado’s Amache camp is revised and redistributed in new third edition

Who writes history? How do we come to understand our country’s incarceration of 120,000 Japanese and Japanese Americans without due process during World War II?

It takes time to assemble the stories of what happened, decades in fact. In the case of Colorado’s concentration camp, Amache, where some 7,500 Japanese Americans were held between 1942 and 1945, stories were scattered and untold for decades. Extensive records of the camp were held in local, state and national archives, but as historian Carolyn Steedman says, “nothing happens to this stuff, in the Archive. It is indexed and catalogued . . . But as stuff, it just sits there until it is read and used and narrativized.”

It fell to Robert Harvey, a Douglas County high school teacher, to read and use and narrativize not just archives about Amache but to conduct interviews with aging survivors whose stories would be lost if not told.

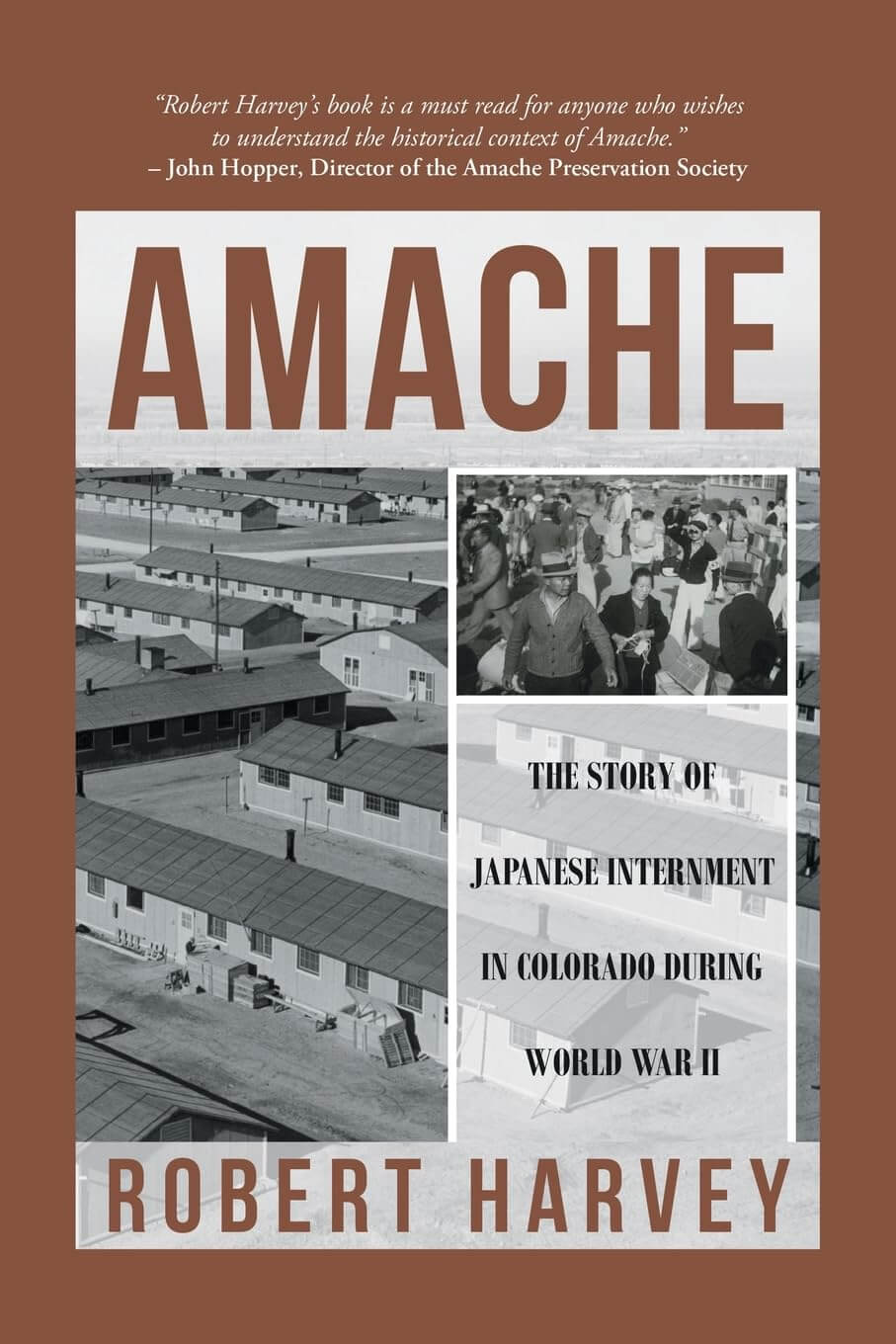

Harvey’s book Amache: The Story of Japanese Internment in Colorado During World War II, originally published in 2003, fell out of print for many years. But demand held steady, and Camp Amache is attracting new interest given its 2022 designation as a National Historic Site, nearly eight decades after its closure. That made it more urgent for Harvey’s book to be revised in a third edition in late 2024.

Harvey’s book Amache: The Story of Japanese Internment in Colorado During World War II, originally published in 2003, fell out of print for many years. But demand held steady, and Camp Amache is attracting new interest given its 2022 designation as a National Historic Site, nearly eight decades after its closure. That made it more urgent for Harvey’s book to be revised in a third edition in late 2024.

Harvey’s book, one of few published or written exclusively about Amache, had modest beginnings. He said the book started with an essay he wrote for a history class, based on his interview with a survivor of the camp. After his account was circulated, Harvey was asked to write the larger Amache story. He said he accepted the task because no one else did. He spent two to three years doing extensive archival research and interviews with survivors, wanting to record their voices before they were gone.

Amache is still a foundational text about Colorado’s camp, listed in bibliographies about incarceration maintained by the Colorado Historical Society, the National Parks Service, Densho, a site dedicated to documenting the incarceration of Japanese Americans during WW II, and many other sites and publications.

Harvey is aware of the limitations of being “a white guy writing about another race.” But he was motivated by the fact that the Asian community wanted their story to be told.

Harvey sets the context for incarceration based on newspaper stories from 1942, just a few months after Pearl Harbor, when long-time racial prejudice against Asians and Asian Americans was reinforced by fears that Japanese Americans living on the West Coast might sabotage the US war effort. It was “racial discrimination, economic greed, and an unfounded fear [that] had wiped clear any remaining constitutional rights” for Japanese Americans, according to Harvey’s text. Conditions were ripe for the decision to evacuate Japanese Americans from their homes on the West Coast to confine them in ten camps, largely in desolate areas of western states: California, Arizona, Utah, Idaho, Wyoming and Colorado. Two more camps were built in Arkansas.

The book opens with the first-person account of 14-year-old Shigeko Hirano whose family was evacuated from their California home to be incarcerated at Amache. Then Harvey steps back from the personal story to look at the larger context of how the US made citizenship impossible for decades. Then the text returns to Hirano’s story of her father’s arrest and imprisonment. Harvey makes this a signature move—from the individual story to the larger context and then back. The third edition of Amache offers footnotes rather than the endnotes included in the first edition, keeping the reader abreast of sources consulted.

On August 27, 1942, Colorado would see its first group of Japanese evacuees arrive at Granada, the town next door to the camp. Coming from California, largely from Los Angeles, the evacuees faced huge challenges in adjusting to a remote and desolate corner of Colorado, their new home for three years.

One of Harvey’s contributions to understanding the incarceration of Japanese Americans is his treatment of how important economics were. Not only did some West Coast residents perceive Asians as an economic threat, largely because of their successes in business and farming, but Japanese Americans in camps were seen as a resource for the war effort, manufacturing necessities (in Amache’s case, their silk screen printing operation made posters for the government) and producing food for incarcerees at their own and other camps.

A good historian, Harvey makes sure he lays the groundwork needed to understand events. Before he looks at the construction of the camp, he looks at how camp locations were found throughout the western US and how Colorado’s Amache site was chosen. Viewing him as a cartographer of sorts, we appreciate Harvey filling in the maps that help us to understand all components of the camp—geographical, political, historical, and cultural. Photos from archives show the site for the camp and then the first internees arriving as well as the early stages of construction, incomplete at the time internees arrived, necessitating their help to build the infrastructure. Black and white photos come from Auraria Library Archives and the Amache Historical Site Archives, add depth to the text, allowing the reader to see all the steps of camp construction.

Context sketched in, Harvey turns to the first train carload of evacuees arriving in Granada after a stay at the Santa Anita assembly center, a racetrack where evacuees bedded down in horse stalls while camps were constructed.

Details of the trip are conveyed through first person accounts, making it clear how remote and foreign the circumstances of imprisonment were to these citizens and immigrants, plucked from their lives and jobs and homes and businesses to satisfy the country’s concern that they might be capable of espionage and sabotage although no evidence of either was ever found. Interviews alternating with news stories from local papers are used to establish conditions on arrival and then during their first weeks of imprisonment. Harvey repeatedly takes the reader from outside to inside the experience, so the reader understands the experience conceptually and viscerally.

Harvey leans into official Japanese American evacuation and resettlement records about camp logistics like fire safety internal security and police, health and welfare, recreation, and schools. Again and again the official record is augmented with the personal experiences recounted from interviews.

Evacuees at Amache were often professionals who held positions as doctors, teachers, artists, electricians in their lives before internment. They worked in the camp hospitals and schools and administrative offices for pay far below their Caucasian counterparts. Highest pay for those with professional skills and unusually difficult duties was $19 a month while Caucasians doing similar work were paid $1,600. Some residents left the camp with work permits to fill positions as agricultural workers for several months at a time.

Amache incarcerees interacted with people in the neighboring communities, and while their money was welcome, they were subject to racial prejudice. Evacuees invited people from surrounding communities to events like fairs, art shows, and various sporting events, but most locals never ventured inside the gates of Amache.

Evacuees lived life as prisoners with some benefits. But they could be revoked at any time. Although evacuees made life as normal and as tolerable as they could, they were still inmates whose rights had been curtailed.

Prejudice in the US in the 1940 toward Japanese Americans was deeply rooted. Common perceptions were that the Japanese were inherently vicious, dangerous and untrustworthy. Outsiders believed the evacuees were coddled and lazy, according to Harvey. The stated goal of camp personnel was to make good citizens of the Japanese Americans, to turn them into patriots who could be trusted. Evacuees were required to take loyalty oaths. Some joined the military, restricted to an all Japanese American unit, one that forged an exemplary record.

The end of the war meant evacuees could leave. They were given bus and train transportation to their home regions and $20 to finance relocation. They had typically lost everything: possessions, homes, businesses, cars, neighborhoods. Some stayed in Colorado, not wanting to face the prejudice on the coast. But most returned to their homes. Transitions were complex and difficult. The end of the war did not diminish prejudice.

The camp closed: “On October 15, 1945, the city known as Amache became a ghost town.” Harvey describes the scene: “Where once stood a people intent on making the best out of captivity now stood piles of tables, dressers, and furniture made of scrap lumber.”

Closing the camp didn’t end the experience of evacuation and imprisonment: “Echoes of its history would resonate into future decades.”

Harvey looks at many politicians’ and historians’ views about what made possible the evacuation and imprisonment of innocent Japanese Americans without due process. He shifts toward the end of the book to consider the future of the site. He is encouraged by John Hopper, a high school teacher in Granada, the town adjoining the Amache site, whose work with students has led to creation of a museum and a website, the collection of artifacts and the telling of Amache’s story.

Harvey ends with this note: “an even larger task might be that of communication. The average American knows very little about the internment process, and fewer still are aware of the relocation centers in western states like Wyoming, Utah, and Colorado.”

Harvey has done his part to make the public aware of Amache, and this third edition will extend his book’s reach to a new generation.

Ceil Malek has an MA in journalism from CU Boulder and an MFA in creative nonfiction from Goucher College. In addition to writing and editing for many publications, she taught in the Writing Program at UCCS for 30 years.

Click here for more from Ceil Malek.