A plea for respecting, saving the living world

New ecopoetry anthology recognizes rapid change in the natural environment since its companion volume appeared in 2013

New ecopoetry anthology recognizes rapid change in the natural environment since its companion volume appeared in 2013

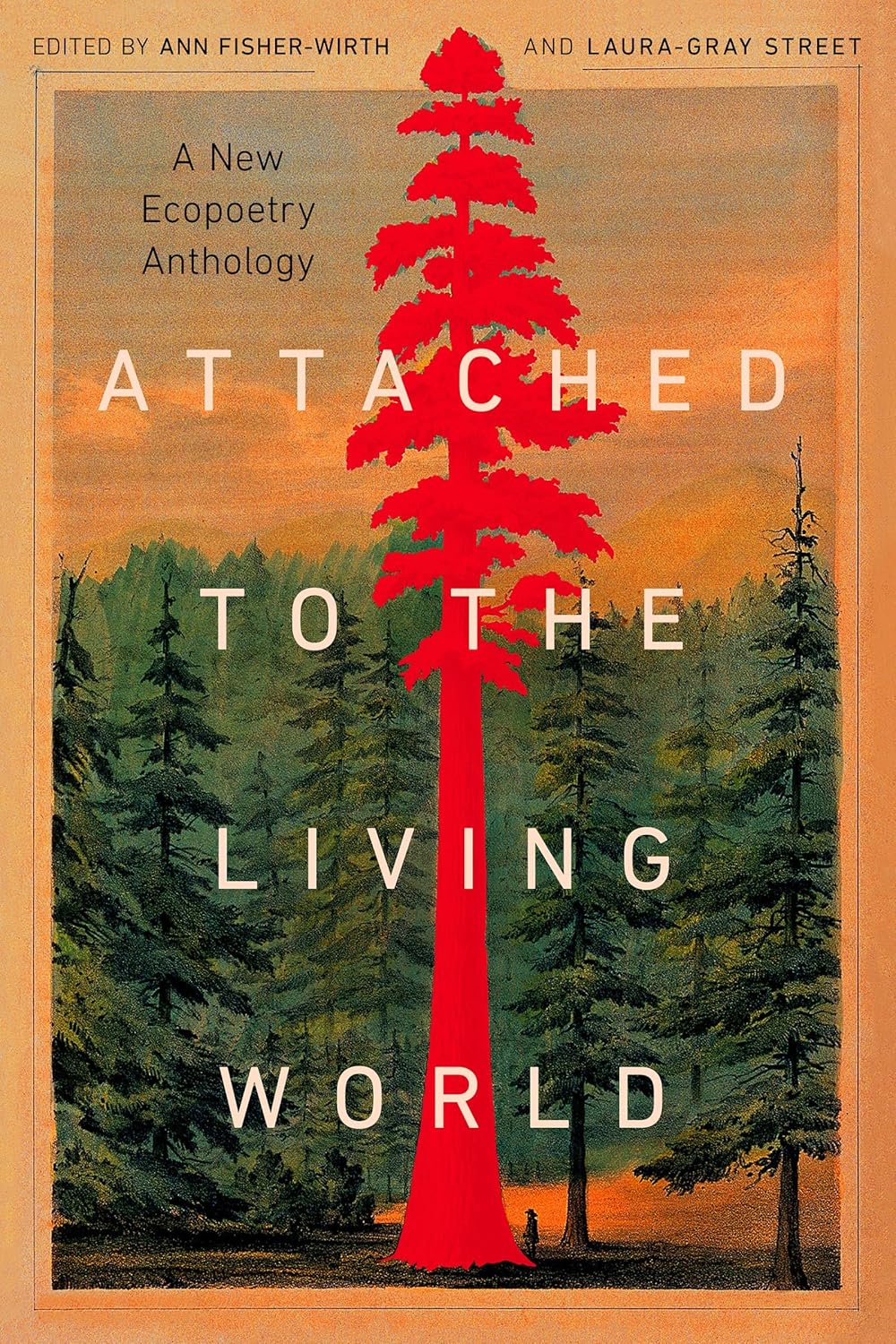

Attached to the Living World (2025) is the companion text to The Ecopoetry Anthology, a book that showcased poems about nature and the environment in 2013. Twelve years later, Ann Fisher-Wirth and Laura-Gray Street gather new voices within this latest anthology. As Fort Collins poet Camille Dungy explains in the foreword, “the world shows up in a renewed record. … These poems exhibit a wide-ranging curiosity, shifting their forms, their tones, and their focus in countless ways so that what seems old might be renewed, what seems disconnected might connect, and what seems lost might be remembered.”

Ann Fisher-Wirth

Laura-Gray Street

Margaret Ronda, in the introduction, describes Attached to the Living World as a meditation on “the capacities and limits of language in a time of climate alteration and species extinction.” These poems claim space on the page, because “language [can] unite and draw together” what may come to be. “At the same time these poems… [also acknowledge the] real alienation [that humans have] from other species.” Broadly speaking, the poems collected in Attached to the Living reflect on our planetary crisis. They are attuned to the intensity of ecological change. “These epochal changes have been categorized as part of the Anthropocene,” in other words how humans have reshaped our world, as well as “our awareness of collective presents and horizons.” Attached to the Living World looks at humans’ culpability in “the planetary scale of anthropogenic environmental alteration” and forms an apology.

The poems included address environmental racism and climate injustice which affects disproportionally marginalized communities of color, as in Santiago Acosta’s “Never Surrender Your Heart to a Nuclear Power Plant,” translated by Tiffany Troy. Acosta builds a contrast between beautiful beaches that should stretch from California to Mexico, but where the border cuts them in two, are anchored in by oil refineries whose gas flares decorate the night. “No one dreams of waking up in front of the sea anymore,” the poem laments. In our separation, our goodbyes, “[t]he beaches will burn to bid us farewell.”

Other poems turn to personal narrative or poetry of witness, using testimony as a response to both environmental and social injustice. Diné poet Sherwin Bitsui gives voice to this: “A field that shivered with a thousand cranes / evaporates in someone else’s backyard.” The Sandhill Cranes’ migratory path is forever altered by loss of leks, the ponds where birds land during mating season which is part of their habitat. These sacred spaces have been “razed,” “drowned” and “salinated” due to an extractive policy that sees the land as a natural resource to be consumed.

Attached to the Living World is concerned with ecological loss, destruction and violence against the land. Yet many poems turn toward renewal, to foster hope and rekindle a sense of wonder in the environment. B.J. Buckley laments habitat loss in “Pronghorn Elegy,” observing pronghorns in their natural habitat, that “when they turn their heads [they seem as if] they own the world.” Despite the pronghorns’ calm, their existence upon the land of their origin is threatened, shimmering like a mirage. They, the pronghorn and the land, have become the “breath and blood in a world of ghosts,” because their land is endangered by encroaching development. “Now every fence an obstacle / that blocks the path to freedom. To the last sparse/ browse. To water. Does stand staring on the verges of / gravel roads to nurse their fawns, blanketed in dust. Bucks pace miles of barbs.” Upon seeing the pronghorns’ separation from their migratory paths, water sources and fresh grazing areas, the narrator chooses to take things into their own hands by becoming a modern Hayduke: “Some of us break locks on headgates. Some of us cut wire in the dark.” Edward Abbey would be proud.

Available at your local independent bookseller or at bookshop.org

Margaret Ronda explains that many poems included in Attached to the Living World “highlight resilience, restoration and a return to ecological and cultural continuance.” For example, Natalie Díaz’s poem, “The First Water is the Body,” recognizes the need for traditional ecological knowledge. She observes that both our sacred waterways like the Colorado River and our own [Native women’s] bodies, are equally endangered. “I carry a river. It is who I am. This is not metaphor.” Díaz writes the Colorado is “silt-red-thick” like blood: “… the river runs through the / middle of our body, the same way it runs through the middle of our land.” Díaz explains that river is “a verb. A happening. It is moving within me right now” and there “can be no life without it.” Díaz mourns the river and what has been done to Indigenous women’s bodies. “If I could convince you, would our brown bodies and our blue rivers be / more loved and less ruined?” she asks. “What we do to one – to the body, to the water – we do to the / other.” Do you think the water will forget what we have done, what we continue / to do? Díaz prods her reader, in the hope of restoring what has been lost and raising awareness.

Additional poems in Attached to the Living World attend to our interconnectedness and our relationships with other humans and non-human relatives. Andrew Gottlieb, in “The Inner Wild,” illustrates those connections. While he fishes a river, Gottlieb spins his cast, notices a moose “stepped free from” willow tangle and sees a hawk head for red cliffs in the distance. He confesses his own, “desire to follow,” to find belonging, to bed down “to sleep with a river.” He contemplates his relationship with the land and hopes others will too before the consequences of our Anthropocene actions become “untethered” and the grace of that flowing river trickles to nothingness and is gone like the hawk on-wing.

Collectively, the poems in this new ecopoetry anthology witness our role within the world, how our actions have consequences, and draws us toward reconnecting with nature, asking readers to care and to act on Earth’s behalf.

Shelli Rottschafer (she/her/ella) completed her doctorate from the University of New Mexico in 2005 in Latin American Contemporary Literature. From 2006 until 2023 Rottschafer taught at a small liberal arts college in Michigan. Summer 2023 she began her low-residency MFA in Creative Writing with an emphasis in Poetry at Western Colorado University, Gunnison. Together with her partner and rescue pup, she resides in Louisville, Colorado and El Prado, Nuevo México.

Click here for more from Shelli Rottschafer.