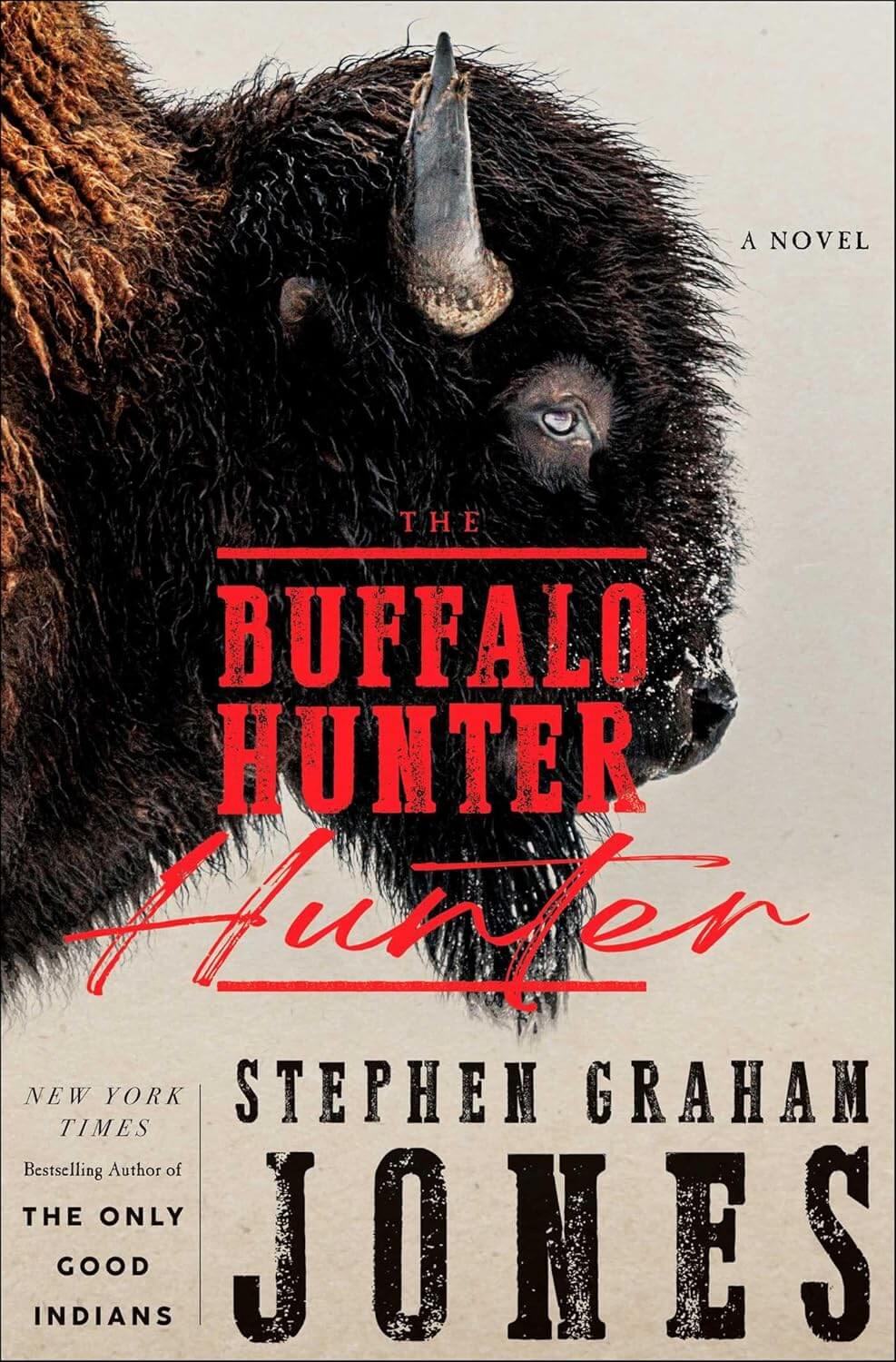

Hunter, bloody hunter

A Western historical vampire allegory from Stephen Graham Jones

A Western historical vampire allegory from Stephen Graham Jones

I confess that although I’ve read Dracula, Frankenstein and two or three books by Stephen King, I’ve never read much horror. And, until last month, when I received an advance reader’s copy of The Buffalo Hunter Hunter, I had never read anything by Stephen Graham Jones. My loss: this book is brilliant. You will want to read it.

Stephen Graham Jones

Jones is the Ivena Baldwin Professor of English at the University of Colorado Boulder and has published more than 40 works, including novels, short stories and comic books. In The Buffalo Hunter Hunter he has created what may well be a new genre, the Western historical vampire allegory.

A worker finds a crumbling journal manuscript in the wall of an old Montana parsonage undergoing renovation. In the journal, Arthur Beaucarne, a white Lutheran pastor who wrote it in 1912, details a series of grisly murders outside Miles City—faces painted, bodies skinned and left to rot on the prairie. Who is killing the residents of Miles City? Are the deaths connected to the skinning of buffalo by white hunters during the mass slaughter campaigns of the 1870s and 1880s? The pastor doesn’t know, but he and others speculate that the local Indians are “turning hostile again.”

The manuscript finds its way to Etsy Beaucarne, a 42-year old single academic who is the pastor’s only living, although distant, relative. Perhaps, she thinks, working on the journal manuscript could salvage her stalled tenure application. She reads that following some of the grotesque, violent murders, Pastor Beaucarne (her great-great-grandfather) receives a visit from an unusual new congregant, a Blackfeet named Good Stab. Good Stab hopes to make a confession to the pastor, whom he calls “Three Persons” (evidently missing some of the nuances of Christianity). As he reveals his story, Pastor Beaucarne records both Good Stab’s story and his own reaction to it. Things get weird; among other things, Good Stab hates bright light. His story is full of ghostly, supernatural elements, and as he confesses to a rampage of carnage, confusion and brutality, the pastor becomes more and more agitated.

The Buffalo Hunter Hunter is a revenge story, the revenge of one Indian who can’t die, “the worst dream America ever had.” It is bloody, visceral and violent. It is also funny. The prose is fast-paced and the story compelling. Despite its length, the book dramatically builds terror and suspense, spooling out connections across time and between characters, each looking in their own way for justice and redemption.

Stephen Graham Jones grew up in Texas and is an enrolled member of the Blackfeet Tribe of the Blackfeet Indian Reservation of Montana. He has researched the history of the Blackfeet in detail (don’t skip the excellent Acknowledgements). The plot of The Buffalo Hunter Hunter hinges on events before and after the Marias Massacre of 1870, when 217 peaceful Blackfeet were murdered by the U.S. Army.

Jones is obviously familiar with Colorado author John Williams’ Butcher’s Crossing and Bram Stoker’s Dracula. Indeed, The Buffalo Hunter Hunter can, like Dracula, be classified as Gothic horror and, like Dracula, it takes an epistolary form. The main events take place between 1870 and 1912, bracketed by Etsy’s story beginning in 2012 and ending in 2013. Although the word “vampire” isn’t used, the character who infects Good Stab—the Cat Man—is European; Good Stab’s contagion, like the “white scabs” disease, is foreign and invasive in origin. Its effect is that the hunter hunts hunters.

story beginning in 2012 and ending in 2013. Although the word “vampire” isn’t used, the character who infects Good Stab—the Cat Man—is European; Good Stab’s contagion, like the “white scabs” disease, is foreign and invasive in origin. Its effect is that the hunter hunts hunters.

Yet instead of the Eurocentric Gothic setting of being alone in a rotting manor house or a coastal castle, the isolation and confinement here result from the vast, detached wilderness of Montana. Distanced from his family, community and culture by his transformation, Good Stab suffers his psychological alienation individually even as the animals and the people of the land suffer collectively. And while the Cat Man appears in an iron cage, Good Stab’s metaphorical cage is at least as confining.

These supernatural elements—the Cat Man, Good Stab’s transformation into the Indian who cannot die, and his merging with animal spirits—mix together with the ghosts of the black horns and the appearance of a white buffalo calf to signal Good Stab’s separation from his tribe and culture. As the elements of his culturally embedded life are serially removed by the white settlers—especially the white trappers and buffalo hunters—Good Stab and other members of the tribes lose their human moorings and live more like animals.

The Buffalo Hunter Hunter presents the moral ambiguity of Pastor Beaucarne and Good Stab with nuance, directly and by using metaphor and allegory. For example, “Beaucarne” means “good meat,” and “Good Stab” indicates a lethal blow, foreshadowing the bite of a blood drinker. Both Pastor Beaucarne and Good Stab lose track of time, in different and perplexing ways: Good Stab forgets his people, his culture, and becomes an animal, and Pastor Beaucarne intentionally forgets his past. The theme of forgetting and remembering extends to Etsy as well. She is trying to discover a past she is connected to by blood but about which she understands little.

The initial sections of Good Stab’s confession chapters can be confusing until you become accustomed to his vocabulary and descriptions. Stick with it. The resolution of this book is powerful—a bloody critique of a bloody time in the West.

Read “with a good heart” until “your pipe is empty.”

Perrin Cunningham is Associate Editor/Publisher of Rocky Mountain Reader. She is the former director and curator of The Heller Center for Arts & Humanities at the University of Colorado-Colorado Springs, where she taught philosophy and humanities. An accomplished equestrian, she also enjoys skiing, hiking, cooking, and reading in bed or in the hammock under the apple tree.

Click here for more from Perrin Cunningham.