Uncovering a family’s defiant struggle

Denver author searches for her family’s largely untold story in compelling memoir

Denver author searches for her family’s largely untold story in compelling memoir

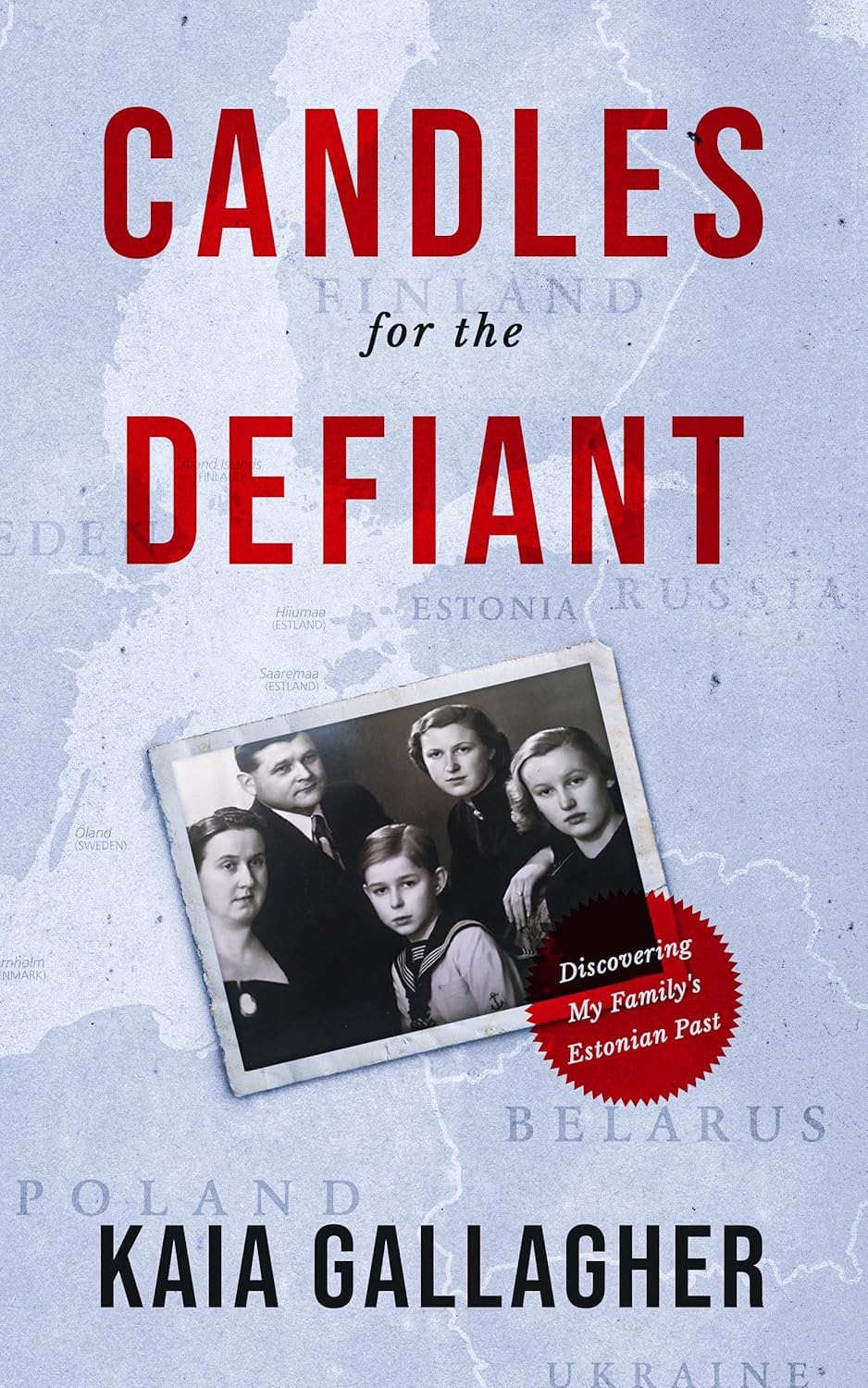

Kaia Gallagher always felt she was missing part of herself. Her Estonian mother, Kaia Vares, who escaped from Estonia toward the end of World War II, was reluctant to share stories about the trauma her family experienced during the war. Candles for the Defiant: Discovering My Family’s Estonian Past is Gallagher’s account of her quest to understand her Estonian heritage.

This Baltic nation has at various times been part of Poland, Germany and the Soviet Union, interspersed with periods of independence, to finally win sovereign status in 1991. Despite centuries of foreign domination, Estonians held tightly onto their language, culture and identity.

Kaia Gallagher

Gallagher’s mother’s sister Asta died before they left Viljandi, Estonia, a small lakeshore city southwest of the capital, Talinn. Gallagher’s mother wouldn’t talk about her sister Asta— it was too painful—and Gallagher began to wonder what else she didn’t know. Through extensive research and conversations with remaining family members and other Estonians, she found many stories of courage, heroism and determination to be free, including the tragic story of Asta and Bruno.

At the age of 20, tall, attractive Asta was studying to become a doctor, and was also engaged to a young lawyer, Bruno Kulgma. During the 1920s, they lived a happy, carefree life, but those days ended as World War II approached.

Bruno’s story occupies a prominent part of Gallagher’s book and illustrates the difficulties Estonians faced during the war. He was fiercely patriotic. When the Soviets forced Estonian leaders to sign a nonaggression pact that would allow the Red Army to occupy naval and air bases in the country, he joined the Estonian Students’ Society, a nationalistic fraternity, resolving to resist the occupation.

In June 1940, the Soviets blockaded harbors in Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania, and the streets of Viljandi teemed with Russian troops, tanks and military vehicles. The Communist Party took over the government and moved to nationalize the economy. Estonian leaders and citizens who resisted were arrested, and many were executed.

Bruno, along with his fraternity brothers, plotted ways to infiltrate and sabotage the Soviet takeover. The local Communist Party leaders viewed him as a possible asset, but his goal was to undermine the party while pretending to be an enthusiastic member.

Bruno came under scrutiny after being charged with favoritism in his job assignments. At the same time, he was branded as a Communist sympathizer by his compatriots who did not know he was a true Estonian. Asta carried on her own resistance activities, helping to establish a network of safe houses and passing on information from Bruno to Estonians who were being watched.

In June 1941, the Soviets began deporting Estonians charged with being “class enemies.” In Viljandi, about 750 people—more than 70 percent of them women, children and the elderly—were rounded up, loaded into cattle cars and transported to Siberia. Families were torn apart and, according to later accounts, fewer than half of them ever returned.

“Over the years, my mother rarely spoke about the impact the deportations had on her family,” Gallagher writes. A friend eventually died in  Soviet captivity. “It was a fate that could have easily happened to my mother’s family.”

Soviet captivity. “It was a fate that could have easily happened to my mother’s family.”

When Germany attacked the U.S.S.R. on June 22, 1941, Asta, Bruno and many Estonians were elated as the Soviets were forced to retreat. When the Germans arrived in force in July to drive out the Russians, they were cheered by the residents of Viljandi, who expected to be liberated. Instead, the Nazis took control. Ordered by the Germans to eradicate any remaining Communists, the Estonian police began to detain anyone formerly affiliated with the Bolsheviks. Bruno, who had come under their suspicion, was arrested in the fall of 1941, charged with being a Communist and an enemy of the Third Reich, and imprisoned. Many people in Viljandi believed he was a Communist collaborator.

While he languished in prison and tried to defend himself, Asta, diagnosed with an aggressive form of cancer, grew sicker and weaker. She died Feb. 19, 1942. About a month later, Bruno was found guilty by a German tribunal and sentenced to death by firing squad. The sentence was carried out on April 22, 1942.

Asta and Bruno cast enduring shadows over Gallagher’s family. Gallagher’s mother was sad and angry at the injustice of Bruno’s conviction and execution, and she never forgot Asta and the shock of her early death.

The family remained in Estonia until the fall of 1944, when they fled to a small town in southeast Germany to stay with a relative, just before the Soviets reoccupied Estonia. After living in Frankfurt as a displaced person for five years, Kaia Vares met an American G.I. who helped her emigrate to the United States. He would become Kaia Gallagher’s father.

Gallagher, who now lives in Denver, interweaves the stories of these people in a compelling narrative of struggle, loss, hope and survival.

“As a result of their stubborn determination, Estonia has become the vibrant, prosperous, and fiercely independent nation it is today,” she writes. Each Christmas Eve she lights candles in remembrance of her Estonian family and all they endured.

Candles for the Defiant received a bronze medal from the Colorado Independent Publishers Association signifying it as among the best biographies/memoirs of 2024.

Jeanne Davant is a lifelong journalist and storyteller. A former writer for the Charlotte Observer, St. Petersburg Times, Colorado Springs Gazette, The Indy and the Colorado Springs Business Journal, she contributes to publications including NORTH magazine and the Southern Colorado Business Forum & Digest. An avid reader, she sometimes must tear herself away from the pages of a good book to pursue her other passions, gardening and walking the Colorado hills.

Click here for more from Jeanne Davant.