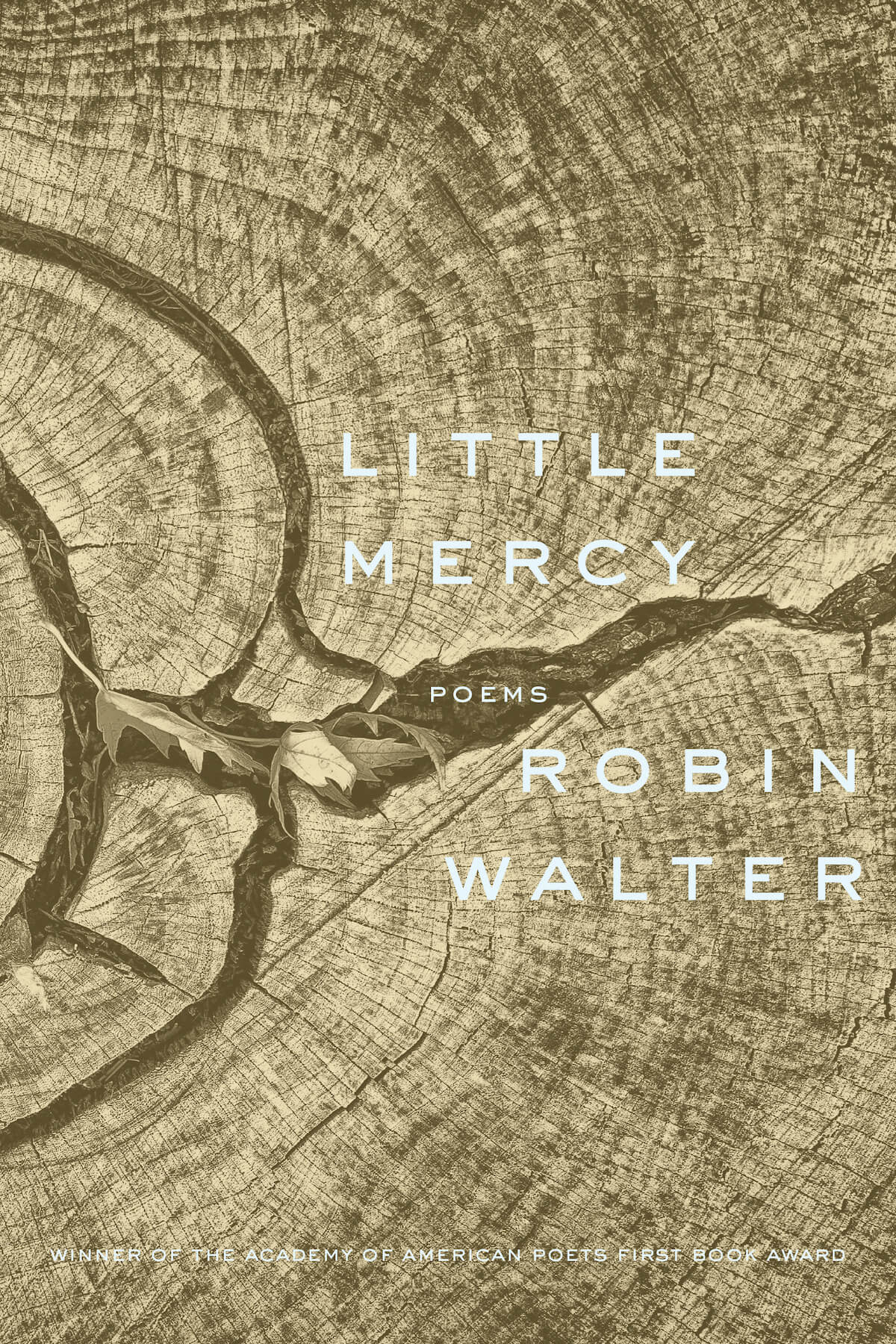

Colorado poet recuperates among a family of wrens, writes award-winning first book

Robin Walter’s Little Mercy attends close-up to the world around her

Robin Walter’s Little Mercy attends close-up to the world around her

Colorado poet Robin Walter’s debut book of poems, Little Mercy, was selected for the prestigious 2024 Academy of American Poets’ First Book Award in April. The award, in Walter’s terms, “was a deep honor and a surprise that opens incredible opportunities.” It means Little Mercy will be published in spring of 2025 by Graywolf Press, a respected nonprofit publisher. And Walter will receive $5,000 plus a six-week residency in Italy next summer.

The prize is awarded for an emerging writer’s first book, the kind of event that typically doesn’t receive the attention of mainstream press, though that’s not been the case for Walter and her book. Announcements of her prize were carried in dozens of news outlets including The Washington Post, San Franciso Chronicle, The Hill, Toronto Star, U.S. News & World Report, CBS, NBC and many more.

“It’s such a rare thing for poetry to make its way into mainstream media, so that was a very happy and surprising response,” Walter said.

Robin Walter

Walter granted Rocky Mountain Reader her first interview since she received the prize.

The story of how she wrote Little Mercy is important to understanding the book. Walter wrote most of the manuscript in a cabin in the Big Horn Mountains in Wyoming, having just sustained a serious accident that left her with a broken jaw, a mouthful of broken teeth, a broken collarbone and a broken foot.

“I wasn’t able to go out in the world very much,” she said. “It was a hard summer for so many reasons. It was the early days of the pandemic with the incredible violence of the murders of George Floyd and Breanna Taylor. One of the graces of that particular summer was that I was able to be on the porch of the cabin in that incredibly beautiful, symphonic landscape.”

Isolated, she said she was “able to keep company with the natural world around me, the animals and light and insects. A family of wrens made a nest in the eaves of the porch. And they provided such company and companionship and laughter and beauty and light-heartedness in a very difficult moment. They were a real gift. I don’t know that I would have been able to write the book without those particular circumstances.”

Celebrated poet Victoria Chang selected Walter’s book for the prize.

“The beautiful and meditative poems in Little Mercy are painterly, showcasing a perceptive speaker with a keen eye,” Chang said in her citation. “These poems quietly and gently ask us to look at all the natural beauty and cruelty (but mostly beauty) we face each day, every minute, every second of our strange time on this earth.”

The poems in Little Mercy are remarkable in their ability to hold the reader close to the poet’s experience of the natural world. After reading it, I was left with bright images of birds and other elements of nature that accompanied me far beyond the page. The poet’s presence and sustained attention somehow transferred to me.

Walter, 34, grew up in Colorado Springs and graduated from The Colorado College where she started as an International Political Economy major and shifted her focus to poetry after being mentored by poetry faculty and visiting writer Jim Moore. A few years after graduating from CC, she entered the Master of Fine Arts program in poetry at Colorado State University. Walter completed her MFA three years ago.

Two throughlines in Walter’s life are her 25-year experience with horses and ten years in outdoor education. She founded Cloud Peak Expeditions, an education-centered organization offering backcountry horse trips into the Big Horn Mountains in Wyoming. These trips aim to “deepen our connection to self, each other, and the natural world.”

For the past three years, she has led pack trips for students in the Equine Sciences Department at CSU where she will assume a full-time faculty position in the fall, teaching in the new Green and Gold Initiative designed to bridge STEM and the humanities. She said she’ll be given “incredible freedom with curriculum design, … teaching the encounter with the more-than-human world and in the spring pairing up with a printmaker. The new program will be interdisciplinary, collaborative and creative.”

Walter is lovely and was deeply engaged, pausing to consider carefully the questions posed in our interview by Zoom. She’s warm, kind, honest, sometimes funny and always generous when talking about her teachers, quick to acknowledge her gratitude to them. She named Dan Beachy-Quick, her advisor at CSU, as someone who shaped her sense of what poetry can accomplish. Writing poetry, according to Beachy-Quick’s ethos, is not a matter of ego or performance; it’s a matter of listening.

Without Beachy-Quick, “I wouldn’t have known how to open the song that comes when we learn to listen,” she said. Camille T. Dungy is another mentor from Walter’s MFA program who made a significant difference in her understanding of poetry.

Walter also thanks poets she only knows through their poetry.

“I feel connected to each poet whose book I have ever read. That is one of the joys of poetry, that it bonds us to one another.” She said the community she found in the MFA program at CSU “was such a salve and balm in a world that doesn’t necessarily value poetry. It’s such a relief and delight and wonder to be surrounded by people who value the effort and care and commitment and time that writing asks of us.”

To be published by Graywolf Press, Spring 2025

The word community came up again and again in our conversation. She finds it essential to her writing practice.

“Writing asks us to be alone. But one doesn’t have to be lonely in it,” she said.

Walter wrote the poems that would become her MFA thesis during her time in Wyoming. It was a project started during the third year of her MFA program after classes moved online because of the pandemic. She was working closely with Beachy-Quick, whose insight that “poems remind us to breathe here and here and here in a breathless world” informed her work.

“In a dark and difficult time, attending to the world around me opened a window that allowed me to walk and breathe,” Walter said. The thesis comprises the bulk of the forthcoming book Little Mercy.

Walter said she hoped the reader would accompany her in the poems she wrote as she found her way through that summer of deep healing. She helps the reader to open to nature in sustained and restorative ways just as she did.

“The wisdom of that work comes from being quiet in the woods,” she said. “Simone Weil talks about ’cultivating a quietness in ourselves.’” The reader is invited to join Walter in that realm.

When asked about her poetics, her understanding of how poetry works in general and how her poems are grounded, Walter was clear.

“I love the idea of a certain kind of poetics that feels welcoming, that doesn’t feel abrasive or cut off or shut off,” she said. “I hope to be generous in attention and that a reader’s attention will join me in that.”

When teaching undergraduates at CSU, Walter tries to find ways that feel less critical and analytical than the ways poetry has been traditionally taught.

“I try to teach that there are any number of ways one can feel when reading a poem. I focus on the feeling of a poem rather than the analysis of a poem,” she said. “I’m interested in what kind of ethics the poem practices or the writing of poetry in general asks us to practice. I hope to emphasize the importance of being a generous reader to be a successful writer of poetry.”

Thinking critically about the class’s reading list and which voices and identities are represented is another key aspect of her teaching.

“I want to make available those kinds of thinking and feeling that might not otherwise be available to students,” she said. “They are increasingly essential in a polarized, violent world.”

Walter’s approach to constructing her book of poems was, not surprisingly, more poetic than technical.

“So much of the architecture of the book was informed by both river and nest,” she said. “The river is a thing that comes up again and again and again. And I think some of the poems contract and swell in the way a river does. Sometimes they expand into the lyric, and other times they’re an offshoot of a stream like an eddy or a braided stream within a larger river.”

The architecture of the nest is important in how the book was made, she explained, thinking of each line as “a little twig” or a comma “becoming a blade of grass.”

“And the ways a nest holds itself, both with order and without, a conglomeration of the world around it, a seeming randomness but an incredibly intricate architecture made with intent and care and time,” she said. “Those were the two elements that influenced the form of the book. Form came not from myself but from the world around me.”

Asked whether her poetry can be considered nature poetry, Walter was typically thoughtful.

“I sometimes struggle with the genre or the idea of nature poetry in which humans are removed from nature,” she said. “So much of my poetry is interested in the natural world and comes from the natural world. I hope it also encompasses the world that extends beyond just nature writing. It doesn’t necessarily have an agenda to be an eco-poetics. It is deeply invested and caring for the world it attends to.”

Asked about the wider poetry community in Colorado, Walter was enthusiastic.

“Poetry is alive and well and vibrant in Colorado,” she said. “So many poets in the Colorado landscape are doing important work and opening important threads.”

Ceil Malek has an MA in journalism from CU Boulder and an MFA in creative nonfiction from Goucher College. In addition to writing and editing for many publications, she taught in the Writing Program at UCCS for 30 years.

Click here for more from Ceil Malek.