Road to destruction

Award-winning book makes us think about the cost of paving the world

Award-winning book makes us think about the cost of paving the world

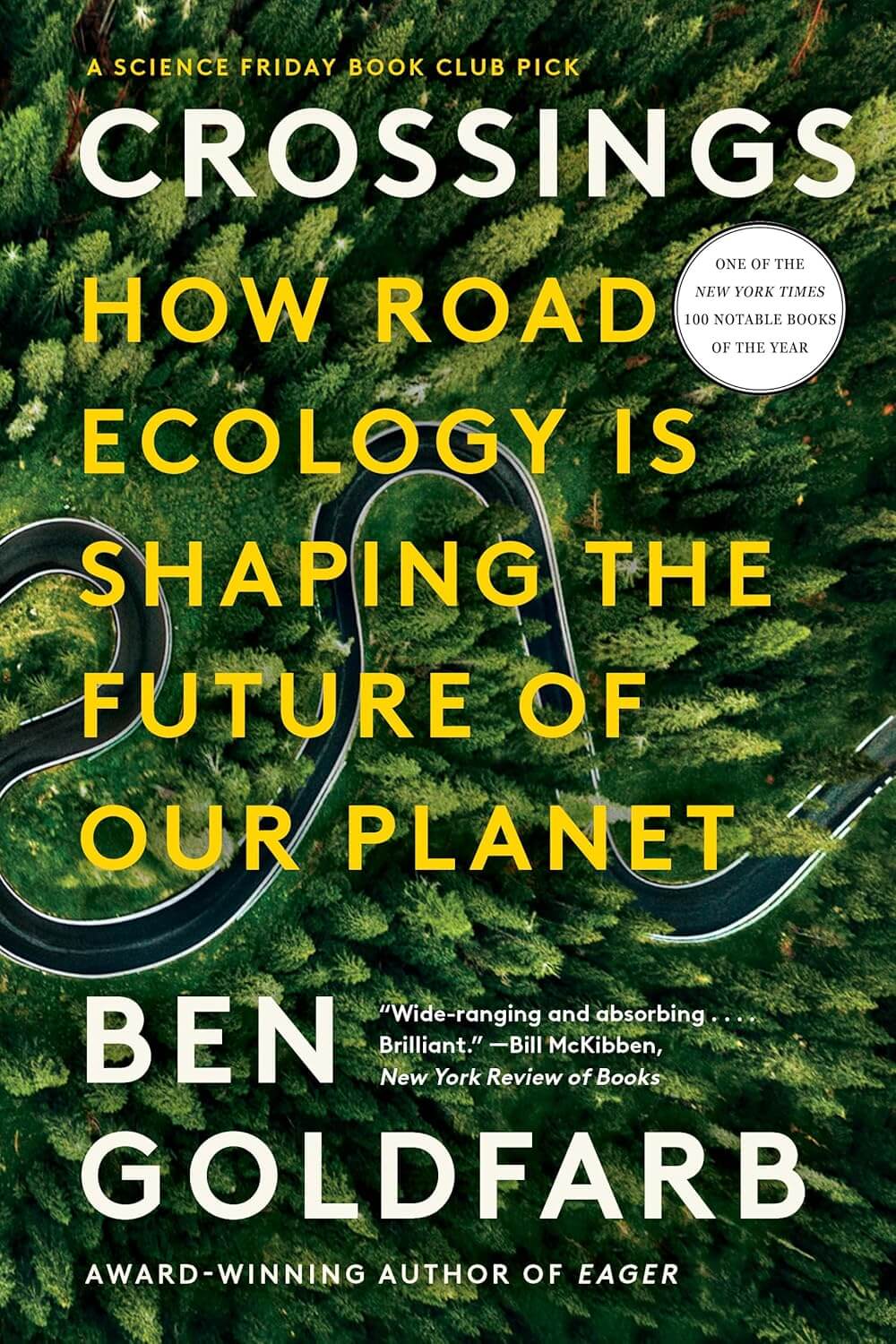

Ben Goldfarb is an environmental journalist and author based in Colorado. His newest book, the paperback version of which was released at the end of 2024, is Crossings: How Road Ecology is Shaping the Future of Our Planet. It was listed as one of the best books of 2023 by numerous outlets, and it earned myriad awards and honors. It was also a finalist for the 2024 Colorado Book Award in creative nonfiction.

Ben Goldfarb

Goldfarb’s writing is full of deep research, expert opinions and personal interactions with the species and landscapes he discusses, and Crossings is a fantastic example of all three. It is an engrossing look at a field of science many readers may not be familiar with, and in the reader it fosters a feeling of immediacy—or even emergency—about the issues he explores. He uses frank, brutal detail and pathos-driven narration to bring the reader into the problem of how roads break up natural landscapes, endangering wildlife and fracturing habitat. Through his descriptions we see the spiderweb of access roads in our national forests, the carcasses of mule deer on highways, birds dipping between cars. When masses of amphibians cross those solids white lines in the countryside, we hear the squishy massacre just as easily as we see the distant specks of oncoming headlights.

Crossings isn’t a “fun” read but it’s enjoyable in a horrifying sort of way for its excellent quality. But it includes many moments that torment the heart. Animal lovers and environmentalists might struggle with the sheer enormity of animal death throughout this book. Mammals, birds, amphibians, reptiles: none are spared. In a chapter titled “The Moving Fence,” in which Goldfarb illustrates the migratory habits of mule deer and how roads interrupt them, he describes a video captured by a thermal camera. The camera was placed on the side of the road by an ecologist trying to determine how many cars become “too many.” In short, at what point is a road busy enough that it becomes a figurative wall, a barrier that most animals won’t even attempt to cross (and those that do perish in the attempt)? Goldfarb explains:

“In one harrowing clip a doe, rendered a pale ghost by the thermal camera, edges up to a two-lane highway, fawns in her wake. She steps forward gingerly, then retreats at a car’s approach. Fifteen seconds elapse. The doe reenters the frame. Her fawns follow. A pickup slams its brakes, taillights glowing; the panicked trio wheels away. Forty more seconds. The doe reappears … She crosses alone, head up, ears pricked. Headlights flare in the distance. Her trailing fawns trot forth. The headlights brighten, the fawns hastening to their mother, death racing to intercept them, one laggard still too slow, hurry up, hurry up!… And then… he’s off the road and into the brush, alive to migrate another day.”

After this breathless scene, Goldfarb reveals, “That video file is labeled Near_Miss.mp4. You don’t want to see BIGcollision.mp4.” Moments like this, rich with tension and tangible detail, appear throughout the book. They ground the reader in the moment, in the action. And because he  does this so adeptly, his prose is sharp enough to pierce even the most stubborn armor of road ecology disparagers.

does this so adeptly, his prose is sharp enough to pierce even the most stubborn armor of road ecology disparagers.

Not everything about Crossings is quite so dark. Goldfarb peppers his prose with little moments of humor, pop culture references and literary allusions. In a chapter about mountain lions trapped by roads in the Santa Monica Mountains, he explains, “Freeways had made the Santa Monicas [the lion patriarch’s] personal Hotel California: he’d checked in, but he could never leave.” Later, in a section about the relationship between roads and salt, he says, “In Elizabeth Bishop’s poem ‘The Moose,’ the titular animal wanders into the road to sniff at a parked bus, a mystical moment that leaves passengers awash in a ‘sweet sensation of joy.’ They might have been less awestruck if they’d known the ‘grand, otherworldly’ creature was merely rectifying a chronic mineral deficiency.” These references alleviate the seriousness of the content, and they offer glimpses into our relationship with wildlife, civilization, and the fraught boundary between the two. The reference to the Eagles’ “Hotel California” helps us understand the entrapment of the mountain lion while absorbing popular readings of the song’s meaning, including the speaker succumbing to death, possibly because of their own greed or the greed of others. The allusion to Bishop’s poem allows us to reconsider how moments in nature we perceive to be beautiful may in fact indicate struggle or decline.

All told, Crossings is a mind blower. Since finishing it, I’ve evaluated my own impact during my daily drive to work, considered migration when I spotted mule deer grazing on the border of I-25, imagined the stories of all those small mammals who didn’t make it to the other side. It’s the kind of book that sticks with you, and it’s the kind of book that, if enough people read it, can spark a social revolution against our collective reliance on the highways that bring us together while simultaneously breaking our landscape apart.

While Marissa Harwood was born in Omaha, Nebraska, she moved to Colorado when she was four days old and considers herself a native. She grew up in the shadow of the Rocky Mountains and spent much of her childhood camping, hiking and building forts in the woods. She earned a BA in English and a Secondary Teaching License from the University of Colorado at Boulder. Later, she attended Western Colorado University and earned an MFA in genre fiction. She has taught English at three K-12 schools and two Colorado colleges. Currently, she lives in Greeley, where she teaches high school, plays with her daughter (a true CO native) and reads a lot of books. She hopes to earn a doctorate in the near future.

Click here for more from Marissa Harwood.