Oh, pioneers

An award-winning history of the late 19th century Great Migration by Black Americans to the western Great Plains

An award-winning history of the late 19th century Great Migration by Black Americans to the western Great Plains

It was the 1860s. After four years of brutal fighting, the American Civil War was over. President Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation, which declared “all persons held as slaves” in the South to be freed. Congress ratified the 13thamendment, abolishing slavery. And the Homestead Act was signed into law, granting 160 acres of public land to any male, citizen, widow, single woman, immigrant pledging to become a citizen and, now, Black American.

The Great Migration was about to begin.

By the late 1870s, an ever-increasing number of Black people had begun making their way from the South to the Great Plains. Newly independent, they were searching for new lives on the dry, windswept prairies. Between 1877 and 1920, Black homesteaders gained title to 650,000 acres in several states. Some homesteaded alone, while others gathered in colonies—DeWitty, Nebraska; Nicodemus, Kansas; and Dearfield, Colorado.

By the late 1870s, an ever-increasing number of Black people had begun making their way from the South to the Great Plains. Newly independent, they were searching for new lives on the dry, windswept prairies. Between 1877 and 1920, Black homesteaders gained title to 650,000 acres in several states. Some homesteaded alone, while others gathered in colonies—DeWitty, Nebraska; Nicodemus, Kansas; and Dearfield, Colorado.

“Their hopes soared with the Great Emancipation and the promises of Reconstruction. It was a time of great jubilee!” according to Richard Edwards and Jacob K. Friefeld, authors of The First Migrants: How Black Homesteaders’ Quest for Land and Freedom Heralded America’s Great Migration.

The First Migrants is being praised as the first account of Black homesteading and recognized for its contribution for understanding the American West. It was awarded the 2024 Caroline Bancroft History Prize from the Denver Public Library, the 2024 Nebraska Book Award and was a 2024 Spur Award finalist, 2024 Jon Gjerde Prize Honorable Mention for best book in Midwestern History, and 2024 ASALH Book Prize Finalist (Association for the Study of African American Life and History). Author Edwards is director emeritus of the Center for Great Plains Studies at the University of Nebraska Lincoln, and Friefeld is a historian at the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum in Springfield, Illinois.

The new wave of settlers arrived with little more than hope and, for many, desperation. The freedom they found in the South with the abolishment of slavery had been fraught with violence, swindle and murder, write Edwards and Friefeld. “By the 1870s, those promises had turned to ash, producing anguish and horror. Black people wanted land—needed land—and after generations working the tobacco, rice, corn and cotton fields, they surely deserved land. But southern whites denied it to them. Blacks began to seek relief elsewhere.”

The First Migrants is a meticulously detailed look at Black homesteaders. “They found in the Great Plains an opportunity to start over, to claim land they could own themselves and on which they could build new futures,” write Edwards and Friefeld. “Land was at the center of their hopes… Owning land in their eyes affirmed that they were now free and fully equal citizens.”

But it wasn’t an easy life. Most Black homesteaders chose to be farmers, but many had to supplement their meager income by working on nearby ranches or in nearby towns. The semi-arid conditions of the Great Plains made farming a vastly different experience than farming in the more fertile South. Crops that grew there wouldn’t grow on their new land, and getting enough water was always a struggle.

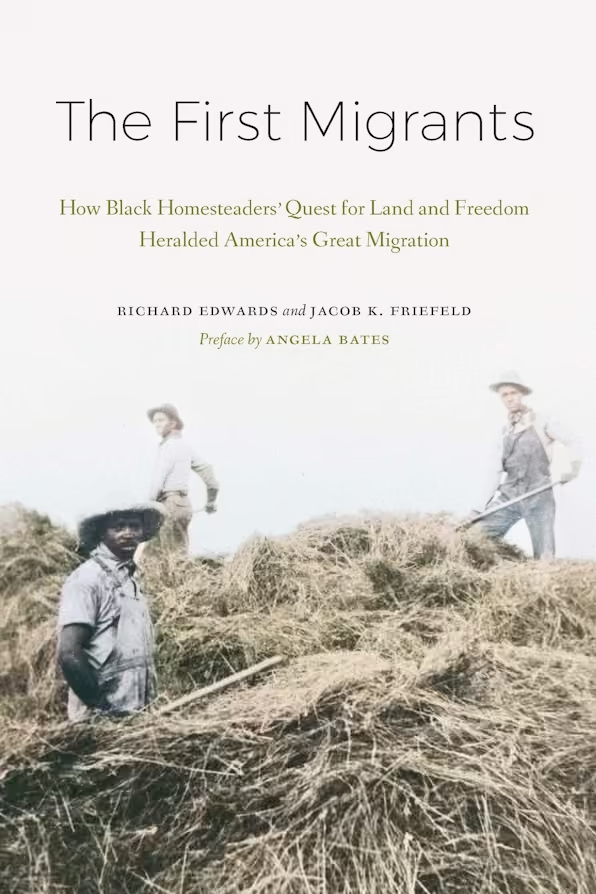

An unnamed pioneer of the Dearfield, Colorado Homestead. Credit: National Park Service

The First Migrants tells the stories of both independent homesteaders and Black homestead colonies. Among the most substantial was Dearfield, Colorado, a community about 30 miles east of Greeley. The largest Black colony in Colorado, Dearfield was established in 1910 by Oliver Toussaint Jackson, a well-known Denver entrepreneur. The son of former slaves, Jackson was born in Oxford, Ohio, in 1862, the same year the Homestead Act was signed into law. When he was 24, he arrived in Denver and six years later had saved enough money to buy a farm in Boulder. He began operating a series of successful restaurants and started developing political ties, a move that paid off when he was appointed to be the governor’s official messenger.

Jackson had a “restless mind,” write Edwards and Friefeld. “He began thinking about building an all-Black farming community in Colorado.” Land was still unclaimed on Colorado’s eastern plains, so Jackson filed a Desert Land Act claim in 1910 for a swath of land 70 miles east of Denver and near the South Platte River. He sold his farm and recruited 19 settlers, and they arrived the following year. Life was hard at first for the settlers who didn’t have an experience with dry farming, but by 1914, Dearfield residents became increasingly successful. The community continued to grow, peaking during World War I, when there were as many as 300 residents, with a concrete block manufacturing company, lumber and coal yard, boarding house and store, and hotel. But harsh conditions, a drought and low crop prices decimated Dearfield and, by 1930, only four residents remained.

Today, it is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. Just a few buildings remain standing and there are no residents. But the fact that it existed is itself a monument to people who “found the space to construct lives filled with joy and meaning as well as hardship and struggle,” write Edwards and Friefeld. “They chose great risk and showed great courage to overcome the challenges they faced… For a time, they made places that were all their own.”

Deb Acord is a journalist and author from Woodland Park, Colorado. For decades, she wrote for The Colorado Springs Gazette, Rocky Mountain News, Denver Post and The Indy. At the Gazette, she was co-creator of Out There, a section devoted to the outdoors of Colorado. She is the author of Colorado Winter and Biking Colorado’s Front Range Superguide and has writtten car trend stories and environmental stories for Popular Mechanics.

Click here for more from Deb Acord.