Miniscule observers in a big world

Sharp reflections in Formations of the West, a poetry collection

Sharp reflections in Formations of the West, a poetry collection

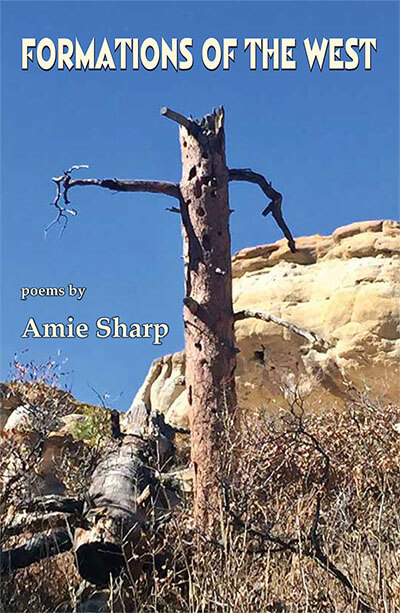

Amie Sharp is an Associate Professor of English at Pikes Peak State College in Colorado Springs, where she teaches courses in composition, literature and creative writing. Her first chapbook, The Sabine Women, a female-forward exploration of the Roman Empire, won the 2018 Emergence Chapbook Series Prize. Her work has been published in dozens of magazines and anthologies, and her poems have been nominated for a Pushcart Prize and Best of the Net. Her newest book, Formations of the West, was published in October 2024 by Main Street Rag Press.

Amie Sharp

In Formations of the West, Sharp dives into a diverse range of perspectives—some old, some new, some tame, some wild. While the poems in this book are thematically connected in a broad sense, each one stands alone as a snapshot of an image, a narrative or a voice. Collectively, they represent starkly different ways of living. Some are dark: there is the mother who shoots her husband in their bedroom, the father who kills his daughter for God, the young speaker who packs a bag full of rifles then sits at the kitchen table and waits for their revenge.

But there are pretty moments, too, observations of the natural world and the ways we fit within it. The collection opens with “West Tennessee, 1980,” a poem like a photograph that evokes the same kind of nostalgia. In it, the speaker recounts the details of their childhood home:

The sky flung persimmon clouds behind

the small hills, and everywhere the roads

mouthed sentinel lines of maple and pine.

Next door our neighbor packed his great oak

with concrete once he saw lightening

had riven its trunk. I was a child, and my questions

were about the dew and how it fell.

This poem highlights the seemingly mundane details of our everyday lives, as well as the details that inexplicably linger in our memories for years. And, as the first poem in the book, it establishes a wondering, a line of inquiry, that is carried throughout. It’s not only a question of where dew comes from; rather, it is a question of the processes of the natural world. It is awe, a realization that there are so many things  happening around us over which we have no control.

happening around us over which we have no control.

This awe shows up again in the poem “The Evening and the Morning,” a beautiful description of the sun rising and setting in the Grand Canyon. As the sun begins to sink, the speaker explains: “And when the moon slung / its crescent against the evening, / the pinnacled shadows watchtowers / against the cascading night, / we saw ourselves as specks / of canyon-shadow—miniscule / much too long a word to describe us.” It is a simple scene—one day with one view—but it evokes in both the speaker and reader a disquieting, humbled understanding of how small we are in the greater landscape of our surroundings. We are spectators; we are recorders; we are reflectors. We do not have the force of rivers that shape canyons, or the blinding power of the sun. We are instead half-seen shadows, there when momentary conditions allow and then gone again, as if we had never existed at all.

Toward the end of the book, in the poem “Late Winter,” Sharp again touches on this admiration of the natural world. In this poem, however, she juxtaposes it with the bleak, tedious moments of a normal weekday:

The barest edge of summit

basks above a bolster

of cloud, the morning sky

coral and crisp. But soon

the commute stutters,

the truck ahead pumping

exhaust through gargantuan

chrome tubes and into my vents.

At a higher elevation

clear air must crest

the startling mountain range.

Down here it’s Monday all over

again, and I have to watch

the road while February

breathes its possibilities away.

Just as the morning air is tainted by the truck’s exhaust, in this poem the beauty of the mountain scene is tainted by the tiring frustrations of the speaker’s drive to work. It makes the reader wonder about the relationship between tangible facts within our daily lives and the abstract truths of our ever-changing, ever-present world. Is one more important than another? How can we balance the concrete details before us with the profound enormity of scenes we have only seen from afar or in the depths of half-remembered dreams?

The reader follows Sharp’s line of questioning throughout the entire book, and at the end we are encouraged to continue wondering, comparing, searching. And if all goes well, perhaps in the process we will find joy, connection, and a healthy respect for forces bigger than ourselves.

While Marissa Harwood was born in Omaha, Nebraska, she moved to Colorado when she was four days old and considers herself a native. She grew up in the shadow of the Rocky Mountains and spent much of her childhood camping, hiking and building forts in the woods. She earned a BA in English and a Secondary Teaching License from the University of Colorado at Boulder. Later, she attended Western Colorado University and earned an MFA in genre fiction. She has taught English at three K-12 schools and two Colorado colleges. Currently, she lives in Greeley, where she teaches high school, plays with her daughter (a true CO native) and reads a lot of books. She hopes to earn a doctorate in the near future.

Click here for more from Marissa Harwood.