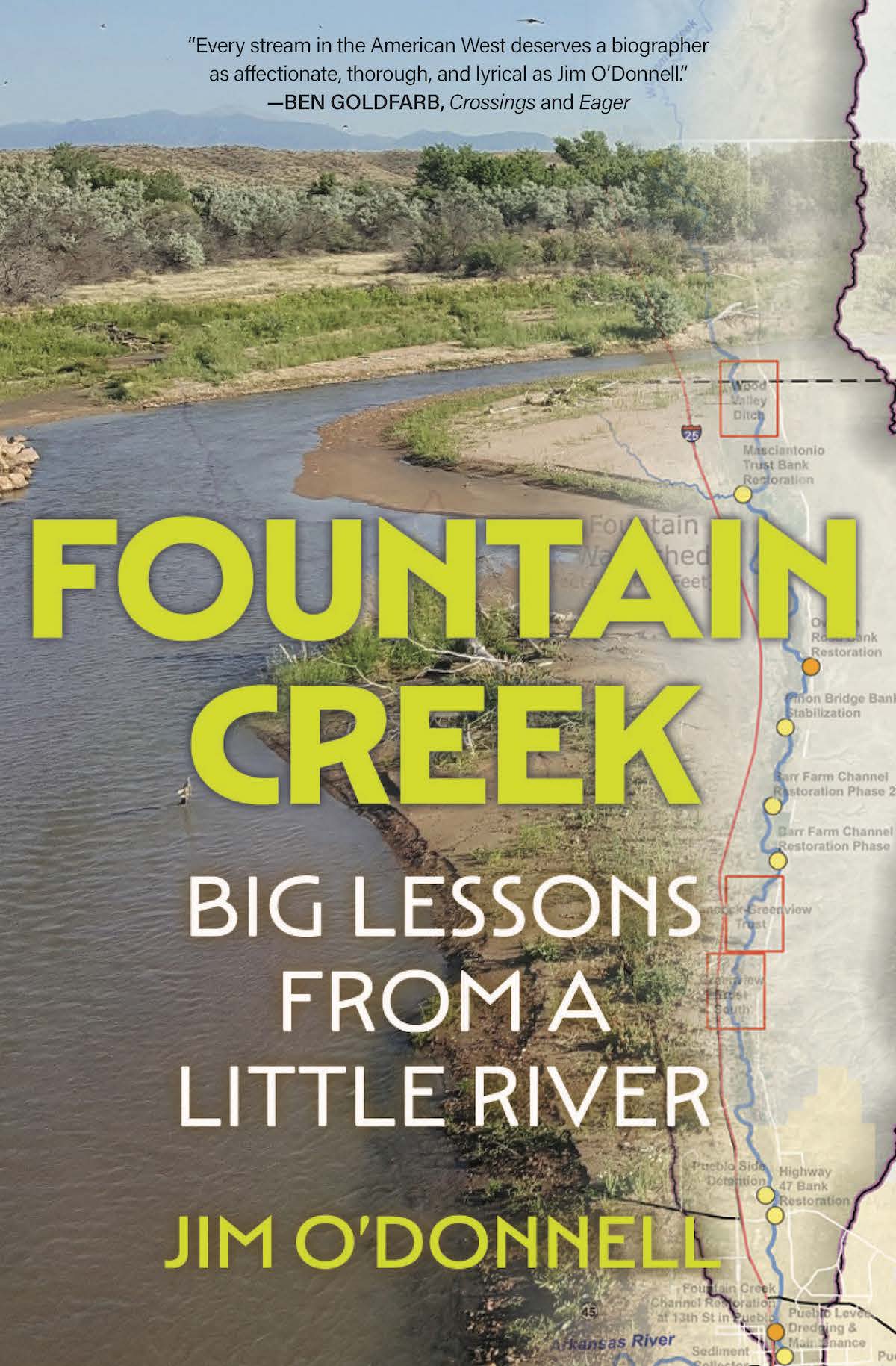

Broken, but still a river with a life of its own

A remembrance and a close look at Fountain Creek, the West’s “most human dominated water system”

A remembrance and a close look at Fountain Creek, the West’s “most human dominated water system”

“Water has the magical power to create beauty, or at the very least, to conceal what is broken.” I was already under the spell of Jim O’Donnell’s Fountain Creek: Big Lessons from a Little Riverwhen I read those words, and that sentence stayed with me.

After nearly four decades in the Pikes Peak region, I’ve been drawn often to the Fountain (as O’Donnell calls it), a watershed that originates up high on the slopes of Pikes Peak and winds down through Colorado Springs on its way to the Arkansas River near Pueblo. As I drive Ute Pass, I know I’m following the mostly concealed path of the waterway, and when the canyon breaks open just west of Manitou Springs, bubbling water sparkles in the shade of the cottonwoods that line the highway.

Jim O’Donnell

In the heart of Colorado Springs, the Fountain attracts deer, foxes, raccoons, the occasional moose and much of the region’s unhoused population. Head south toward Fountain Creek Regional Park and the water cuts a wider path. In the park, it nurtures great blue heron and egrets, more raccoons and more deer. It can look—and smell—bucolic and ugly at the same time, with abandoned shopping carts and chunks of concrete, hunks of metal and other industrial waste dumped into its waters.

O’Donnell, a writer, photographer and conservation activist now living in Taos, New Mexico, was born and raised in Pueblo, Colorado. He grew up exploring the Fountain in the 1980s, fishing for trout, hiking its banks, cataloging the wildlife he encountered, learning about the people he met along the way, and making sense of the changes he observed there throughout his youth.

Today, the Fountain is drastically different than it was in O’Donnell’s childhood. But it’s also the same. “Over the years, [it] has been … known, unknown, forgotten, remembered, misunderstood, blamed, monitored, sampled, screened, and very nearly tamed,” he writes.

“The Fountain is one of the most human dominated water systems in the West,” O’Donnell said recently in an article in the Taos News. In Fountain Creek, he writes about that domination and its consequences: flooding, diversion, damming, litigation, poisoning.

Much of the book is a primer on complicated water rights, laws and regulations that impact the Fountain. Yet the way O’Donnell  weaves together personal recollections and experiences, lyrical descriptions of birds, animals and people, and the Fountain’s history, make it memorable. Among other things, O’Donnell establishes that the Fountain is an integral part in the creation and development of the city of Colorado Springs, founded in 1871 by General William Jackson Palmer.

weaves together personal recollections and experiences, lyrical descriptions of birds, animals and people, and the Fountain’s history, make it memorable. Among other things, O’Donnell establishes that the Fountain is an integral part in the creation and development of the city of Colorado Springs, founded in 1871 by General William Jackson Palmer.

A Civil War hero and entrepreneur, Palmer fell in love with the expanse of land at the base of Pikes Peak. Others were skeptical, thinking it barren and desolate. Decades before Palmer, Dr. Edwin James (the 1820 Long Expedition’s botanist and first non-native person to climb Pikes Peak), offered this bleak opinion: “…it is almost wholly unfit for cultivation and of course uninhabitable by a people depending on agriculture for their substance.”

Palmer, who arrived in 1869, was determined to prove naysayers wrong.

“He set to building his oasis,” writes O’Donnell. “First, he purchased land at the confluence of the Monument and the Fountain, where America the Beautiful Park lies today.” He rounded up investors and the first irrigation canal was dug in 1871. “By the end of the next year, six hundred cottonwoods had been planted along the freshly platted streets. The colony’s growth began,” and Palmer’s dream became a reality.

Today, more than 150 years later, the State of Colorado lists the Fountain as impaired. “When it comes to water quality, the state also suggests you think twice before wading into Fountain Creek. At least not without some protections. There are ‘sharp objects,’ the state says, referring to broken glass, nails, and used needles.” O’Donnell further explains that the impaired designation comes from the presence of high amounts of E. coli, selenium, hepatitis A, mercury, lead and other toxins in the water.

That makes the Fountain sound like an appalling, apocalyptic cesspool flowing through the Pikes Peak region. But it is still a river, O’Donnell reminds us, and “rivers have a life of their own.”

As he explores the Fountain’s past, present and future, O’Donnell also explores the waterway in its current state, setting out on foot along each section and narrating with a voice reverential towards the water and the living things that depend on it. He offers a clear-eyed but compassionate look at the unhoused people he encounters on its banks, and chronicles the trees— elm, ash, willow, cottonwood—and the birds— American dippers, white-crowned sparrows, hermit thrush, blue herons and dozens of other species.

Near the end of the book, O’Donnell acknowledges there is no shortage of literature and music about rivers, creeks and streams, and quotes Olivia Laing, author of To the River: A Journey Beneath the Surface: “The vast, disordered library of river literature signals the power of moving water as thoroughly as does the wearing down of formidable mountains by those same waters.”

O’Donnell’s book is a worthy addition to that library.

Deb Acord is a journalist and author from Woodland Park, Colorado. For decades, she wrote for The Colorado Springs Gazette, Rocky Mountain News, Denver Post and The Indy. At the Gazette, she was co-creator of Out There, a section devoted to the outdoors of Colorado. She is the author of Colorado Winter and Biking Colorado’s Front Range Superguide and has writtten car trend stories and environmental stories for Popular Mechanics.

Click here for more from Deb Acord.