Fighting corruption in the Big Store

Gangbuster recounts the forgotten career of a dogged crimefighter

Gangbuster recounts the forgotten career of a dogged crimefighter

In 1921, when Philip Van Cise was elected Denver’s district attorney, Denver was no longer a rough-edged frontier town, but its Wild West heritage lingered in the form of a thriving criminal underground. Con men plied elaborate schemes to separate gullible marks from their money and were allowed to do so by authorities who often were on their payrolls. They were so successful at the Big Con that Denver became known as the Big Store. As the decade progressed, the Ku Klux Klan tightened its grip on the city and the state.

Van Cise waged a lifelong war against these two evils, but for decades, his name has been little known. In Gangbuster: One Man’s Battle Against Crime, Corruption, and the Klan, award-winning journalist Alan Prendergast makes a convincing case that Van Cise deserves more prominent acknowledgment in Colorado history.

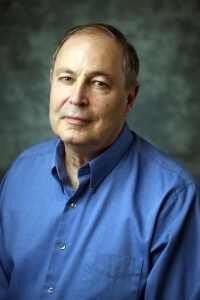

Alan Prendergast

Prendergast is the author of The Poison Tree, a book about the Richard Jahnke child abuse and parricide case, and uncounted articles over a long career as a journalist about the justice system and historic crimes. He won the Society of Professional Journalists’ 2015 Eugene S. Pulliam National Journalism Writing Award for his article “Bloody Ludlow,” an account of the 1914 Ludlow massacre published in Westword, where he was a longtime staff writer. He teaches journalism at Colorado College.

A cast of colorful characters livens up Gangbuster’s pages: Lou “The Fixer” Blonger, head of Denver’s confidence gang; John Galen Locke, the Grand Dragon of the Colorado Realm of the KKK; District Court Judge Clarence J. Morley, a high-ranking Klansman who became Colorado’s governor; Denver Mayor Benjamin Franklin Stapleton, a one-time Klan member who went on to significant achievements after renouncing his Klan connection; and, of course, DA Van Cise.

A native of Deadwood, South Dakota, Van Cise had lived in Denver since he was 16 years old and returned there after serving in World War I as an intelligence officer. In his four-year term as district attorney, he prosecuted murderers, rapists and petty thugs, earning a national reputation for using investigative methods that were decades ahead of their time—electronic surveillance, undercover operations, stakeouts and interception of communications—to lay bare the operations of Blonger and his cohorts.

Prendergast describes in detail how grifters fleeced their marks out of large sums of money. They were welcome in Denver as long as Blonger got his cut. Bringing them down was no easy task, since the Blonger gang was in league with police and city officials.

But Van Cise’s investigations led in 1922 to the roundup of more than 30 suspects in one day and the conviction of 20 criminals, including Blonger.

Prendergast devotes the first half of Gangbuster to Van Cise’s elaborate jousts with the con men. In the second part of the book, he tracks the DA’s war with wilier foes — Locke and the KKK.

In the mid-1920s, the Klan was extending its white supremacist grip throughout America. In Denver, white-robed and hooded Klansmen marched four abreast in parades through downtown Denver and infiltrated Denver’s police, city government and the state’s highest offices. Thousands attended meetings and cross-burnings on South Table Mountain near Golden.

Locke, a consummate performer and dealmaker, used theatrics, lies, intimidation and patronage to build the Colorado KKK into one of the most politically powerful organizations in the country, with influence at the highest levels of state government. Van Cise saw him, Prendergast writes, as the con man he was, and fought him in the courts, the press and the political arena.

Though the Colorado Klan eventually fell into a sinkhole of internal strife and ineptitude, more than a shovelful was turned by cases Van Cise filed during his waning days in office.

In his subsequent private practice, fraud cases paid the bills, but Van Cise also pursued former Klan members when cases arose. He remained a thorn in Locke’s side, vigorously going after the former Grand Dragon over a $445 debt. Locke’s supporters turned against him as Van Cise helped bring to light information about his shady schemes and backroom deals.

By 1926, the Klan was no longer a potent political force in Colorado, and by the end of the decade, the Klan’s influence had significantly dwindled nationwide. But Van Cise continued to dog its members. He railed at the Klan during a speech on Memorial Day 1926; the Klan retaliated by burning a cross in his front yard. But by then, as Prendergast notes, “the Klan was finished.”

Locke continued to try and wield influence in local and state politics, with little success. At age 63, on April Fool’s Day 1935, he  dropped dead of a heart attack in a suite of rooms at the Brown Palace Hotel that was headquarters for a Denver mayoral candidate. After distancing himself from the Klan, Stapleton won re-election as Denver’s mayor in 1927 and served three subsequent terms. Under his leadership, several city-defining projects, such as Denver’s municipal airport, Red Rocks Amphitheater and the Civic Center complex, were completed.

dropped dead of a heart attack in a suite of rooms at the Brown Palace Hotel that was headquarters for a Denver mayoral candidate. After distancing himself from the Klan, Stapleton won re-election as Denver’s mayor in 1927 and served three subsequent terms. Under his leadership, several city-defining projects, such as Denver’s municipal airport, Red Rocks Amphitheater and the Civic Center complex, were completed.

Former Gov. Morley ended up in prison and in disgrace after his conviction in a fraudulent stock scheme.

Van Cise’s book on the Blonger investigation, Fighting the Underworld, was published in 1936. He never stopped speaking out and acting against those he viewed as wrongdoers, no matter how powerful the perpetrators. But after the decline of the Klan, his name “vanished from the newspapers for years at a time.” Prendergast posits this was in part because of his inflexible moral rectitude and because people didn’t want to be reminded of the foes he fought against.

Van Cise continued to practice law into the 1960s, though he semi-retired in 1959 and left his son Edwin in charge of the law practice. After years of declining health, he died on Dec. 8, 1969, at age 85.

With Gangbuster, Prendergast joins the ranks of authors like Erik Larson (Devil in the White City) and David Grann (Killers of the Flower Moon), who write about historic true crime in journalistic rather than academic style. Prendergast cites many of his sources in the text and in his author’s note at the end of the book, eschewing the use of footnotes to focus on the narrative. Picky readers might wish he had appended a chapter-by-chapter acknowledgment of his sources at the end of the book, as some historic true crime authors do. But Gangbuster is extensively researched and succeeds not only in telling a compelling story but also in drawing parallels between Van Cise’s era and today.

The Gangbuster didn’t eradicate the underworld, but he exposed it to the light of day, Prendergast says. He didn’t eliminate the Klan but revealed the criminal nature hidden beneath its populist front.

“The kind of criminal conspiracies he fought are still with us, in more sophisticated guises, and so are the deceptions that go with them,” Prendergast writes. “But we can learn a great deal about how to fight them from his example — the methods he employed, the determination he showed, the ways he snatched victory from defeat without getting snatched himself.”

Jeanne Davant is a lifelong journalist and storyteller. A former writer for the Charlotte Observer, St. Petersburg Times, Colorado Springs Gazette, The Indy and the Colorado Springs Business Journal, she contributes to publications including NORTH magazine and the Southern Colorado Business Forum & Digest. An avid reader, she sometimes must tear herself away from the pages of a good book to pursue her other passions, gardening and walking the Colorado hills.

Click here for more from Jeanne Davant.