A risky proposition

Debut novel inhabits Alaskan wilderness with two souls, lost and searching

Debut novel inhabits Alaskan wilderness with two souls, lost and searching

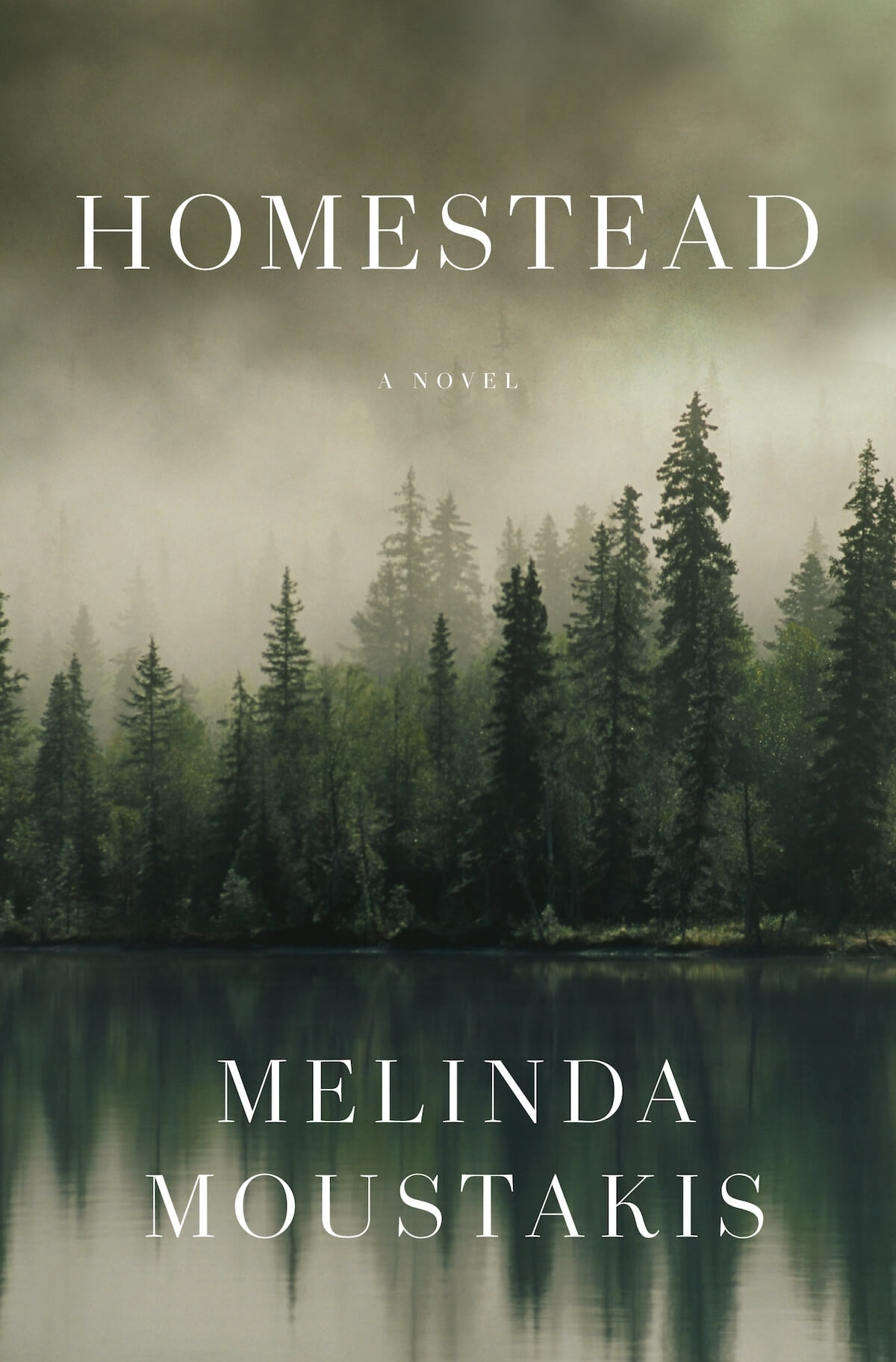

Homestead, Melinda Moustakis’s eloquent debut novel, tells the story of two impulsive dreamers who take a gamble on each other as they struggle to build a life together on 150 acres in the Alaskan wilderness.

Moustakis, born in Fairbanks, Alaska, clearly knows about life in the frozen north. Her grandparents homesteaded in the same area as Lawrence and Marie, and her 2011 story collection, Bear Down, Bear North, depicted the harsh conditions of the country and the tough, tenacious people who lived there. (Bear Down, Bear North won the Flannery O’Connor Award and was a National Book Foundation 5 Under 35 selection.) Moustakis lived in Denver before relocating to Providence, Rhode Island. Homestead was nominated for a 2024 Colorado Book Award in literary fiction.

From the get-go Homestead perceptively explores the risky proposition its main characters have undertaken.

Melinda Moustakis

Lawrence Beringer, a 27-year-old greenhorn from Black Duck, Minn., is a taciturn son-of-a-gun, suffering from trauma after fighting in the Korean War. Marie Kubala, 18, runs into him on a July night in 1956 at the Moose Lodge while visiting her sister and brother-in-law in Anchorage. She’s up for an adventure, eager to shake off the unresolved sadness of a shiftless childhood in Conroe, Texas.

Alaska, fabled land of glaciers, grizzlies and gold, won’t achieve statehood for another three years, but there’s a robust spirit of possibility in the sprawling, wild country. Under the Homestead Act of 1862, thousands of people flock to the territory to claim federal land for small farms.

For Marie, the promise of land is a chance to make something of her life.

“There are scores of men in Alaska, their faces a worn stare, and the first man Marie likes the look of who has prospects and could be tied down long enough to marry, she will have him,” Moustakis writes. Lawrence, skinny, strong and tightly-wrapped, hardly seems like a prize, yet something about the straightness of his spine, of the way he steadfastly fills his plate again and again, appeals to Marie. When he hands her a note with the words “150 ACRES” written on it, their fate is set in motion.

Lawrence marries Marie on the flimsiest of premises—because she said yes. “You know what I have and what I got to offer,” Lawrence gruffly tells her and indeed, she does. Lawrence has blindly selected a parcel of land from the Bureau of Land Management and resolves to build a cabin near Point Mackenzie, in the shadow of snow-capped Pioneer Peak. Armed with a map and a promissory title for lot 04110, he dreams about building a cabin and a life.

To secure the deed to the land, he must prove to the government that he has what it takes: felling trees, clearing land, growing crops, putting down roots. It will be a place “where his children will call the years,” Moustakis writes. “Where he will cut the timber and till the ground and build a cabin of his own measure. He will claim what he is owed. And by the work of his hands this will be all his.”

Challenges abound. Not only must Lawrence and Marie learn how to live under spartan living conditions and brutal weather, but they must also learn one another—their pasts, their unresolved traumas, disappointments and dreams.

The exterior story of Homestead is about surviving the weather, the bears, the wolves and midnight trips to the frozen outhouse. Chop wood, carry water. But at its core, the novel is quietly intense, telling a visceral story about what happens when two stubborn, wounded people try to live together—despite barely even knowing each other. The novel spans three years and is told through alternating points of view.

Chop wood, carry water. But at its core, the novel is quietly intense, telling a visceral story about what happens when two stubborn, wounded people try to live together—despite barely even knowing each other. The novel spans three years and is told through alternating points of view.

Moustakis’s prose is restrained and understated, providing uplift through quiet, incantatory passages like this one: “Snow came and went, a promise and a lie, and the turned trees lost their finest gold and yellow leaves in the wind. The scrape of moose antlers on branches and the rustle of willow shrub, the rut, and the bulls in a fight over the cows, the hollow racket of antler thrown against antler, the echo through the low.”

Finding security proves elusive for Marie and Lawrence. While Lawrence is stoic and imperturbable, Marie is vulnerable, naïve, and hungry to know her man. How will they ever mesh, Lawrence wonders. “He is building this for his children and his children’s children—a notion that steadies him, but what of Marie, the everyday of living here with each other, together? How would the days turn into years?”

It’s this inner story, of two people valiantly struggling for their piece of heaven in the wilderness, that makes Homestead such a satisfying and immersive experience. Relief comes in small revelatory moments, whether it’s savoring a swim in the lake, tracking an eagle’s flight over birch trees or getting a little tipsy on homemade cherry wine.

Trouble surely comes and grief alters the relationship. Grief, which has taught Marie to be tougher, and more resilient, gives the story forward momentum. What ensues as this couple tries to regain their balance—and earn the deed to the land—is a stark testament to American spirit.

D’Arcy Fallon, an award-winning former Colorado Springs Gazette reporter, lives in Springfield, Ohio. A professor emerita of Wittenberg University, she is the author of a memoir, So Late, So Soon (Hawthorne Books), about living in a religious commune in the ‘70s. Her work appears at https://darcyfallon.substack.com.

Click here for more from D'Arcy Fallon.