Shedding light on the night sky

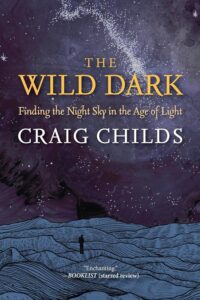

Our Moon author Rebecca Boyle interviews Colorado author Craig Childs about his new book, The Wild Dark: Finding the Night Sky in the Age of Light

Our Moon author Rebecca Boyle interviews Colorado author Craig Childs about his new book, The Wild Dark: Finding the Night Sky in the Age of Light

The first time I met Craig Childs in person, he told me he was astonished by the brightness of the mountain where I live.

Childs was in Colorado Springs for the Colorado Book Award ceremony, for which his book Tracing Time was nominated, and he decided to camp at Cheyenne Mountain State Park, which is a couple miles from my house. The mountain is lit up at night because of Cheyenne Mountain Complex, which most of us here still call NORAD—the North American Aerospace Defense Command. There is a huge door in the side of the mountain, which leads to several buildings erected within its granite confines, and its parking lot is lighted at night.

I tried to defend the darkness out my back door, explaining that the light from NORAD shines southerly, away from my house. But my argument was beside the point. Childs was right: Cheyenne Mountain is bright at night, it is undeniable. And that is a situation that should not be. It is an unnatural state, a huge uncontrolled experiment, a crushing blow for the natural ecosystem and our shared heritage of the night sky. The mountain is bright, and if you are standing in the NORAD lot, you will not be able to see the stars above you. You would quite literally need the radar system, and not your own eyes, to see anything above you at all.

Craig Childs

In Childs’ latest book, The Wild Dark: Finding the Night Sky in the Age of Light, the longtime nature writer explores what it means to lose that natural sky, and to reconnect with it on a journey through the American Southwest. I have written about this subject for more than a decade, and I was struck by Childs’ ability to make darkness come alive.

“There has never been this much light,” he writes. He’s riding on a kitted-out bicycle through the desert.

Childs, who lives in Norwood, Colorado, is the author of several books on the landscapes and history of the American West, including The Secret Knowledge of Water and House of Rain, and he is a spoken-word performer and river guide. In full disclosure, we know each other because we both write for the group science-literary blog The Last Word On Nothing. His trip from the Mojave to the Great Basin was not his first foray into the wild dark, but it is the first time he devoted an entire book to the subject. Childs traveled from the brightest place imaginable—Las Vegas and the Sphere—to the darkest spot he could find, traveling along a scale known to amateur astronomers for the ability to judge their “seeing.” The Bortle scale, named for an amateur astronomer named John Bortle, measures the darkness of a skyscape. Childs brings the scale down to Earth by physically traveling along it, from Las Vegas’ astonishingly bright Bortle 9 to the (surprisingly geographically close) utter dark of a Bortle 1 desert.

Along the way, he invites you, too, to look up and find the wonder and stories that filled our ancestors’ nights, and just as easily can fill ours again, if we choose.

Craig and I spoke after he arrived home from another very bright place, New York, just before his book’s publication date of May 27. An edited transcript of our conversation follows.

Rebecca Boyle: House of Rain was the first book I read of yours. How do you think this book felt to write compared to House of Rain, or Secret Knowledge of Water? To me, this feels very much like a Craig Childs book, where you are my desert guide, but it also feels a little bit more authoritative—or maybe you have a different posture in this book. I wonder if it felt like that to you writing it.

The Wild Dark: Finding the Night Sky in the Age of Light by Craig Childs (Torrey House Books, releases May 27). Purchase from your local independent bookseller or at Bookshop.org.

Craig Childs: Each book I’m writing focused in the West, in the Southwest, is about a different element, a different major feature of of being in this place—whether it’s archeology, or if it’s animals, rivers, geography. To me, this made sense as the next step, because the night sky is such a major feature of of Western landscapes, or skyscapes. It’s something that trickles in everywhere and in everything that I write. There is always a night sky, and there’s always going to be an experience at night. But I haven’t focused on it, and this is how it’s unique on this side of the continent, and that we hold these last big islands of full night skies.

I feel like I’ve thought about the night sky so much and had so many experiences underneath it, that this is a lifetime gathered up, probably more than any other [of my] books. Archeology came later in my life. Animals came in here and there throughout my life, but nothing was there as long as as the sky—that’s there from the beginning. I think writing about it is accessing something that’s much more elemental than many of the other things I’m writing about.

RB: In the book, you go on this trip, but it’s also like you are staying in one place, if that makes sense—you’re traveling on the ground, but you’re still in the night sky the whole time, whether you’re in Norwood or you’re in Las Vegas.

CC: That was another thing about this book that was very different for me, is that usually I’m all over the map, in a lot of different locations. And this was really nice that it all happened in 10 days, as opposed to it all happened over five years, or whatever it is. I really was focused and and I didn’t have to rein it in as much as I rein in other things. Often, I’m working with the narrative, like, ‘we’re here, we’re there; we’ve got a a tense change,’ and how to transition in and out of that. All the little mechanics of a more complex narrative didn’t trip me up. I really want to ground the reader as I write, and take them to a place and really sink them into the sensations of that. And in this case, the biggest change, other than night by night the sky changing, was going from the Mojave Desert to the Great Basin desert. That, for me, was a significant change, but on the page, it’s subtle. So, I didn’t have to to transition and and play with the narrative as much as I usually do.

Available at your local independent bookseller or at Bookshop.org

RB: I know you’re on the road a lot. But when you are in a place where you feel like you are at home, what does the sky feel like to you? Do the stars dominate, or is it just a lack of artificial illumination that dominates? And how does that sensory experience make you feel home?

CC: Places where the stars dominate definitely feel like home. It’s not just the dark on the ground, it’s the presence of stars and and the presence of the Moon; just being able to look up and see clearly and be able to see the Moon go through its phases. I just got back from New York City, and I could spot some stars here and there, and I did manage to find the Moon. But the Moon seems like such a stranger in the city. And you don’t know if it’s waxing or waning. You’ve lost your relationship through time with it. And the same for the stars; I do feel like I align myself with constellations at different times of the year. I’ve been away from home for a while, for a few weeks now, and I’m not sure what’s in the sky. I kind of lose my my bearings a bit.

I think in urban environments, I just forget to [look up] because you’re not really going to see that much. And so it’s not as bold of an experience. Your brain’s just not looking for information anymore from up there, because there really isn’t that much information, whereas getting to a a big, dark sky full of stars, there’s so much information. It’s both on a very physical level, of going, ‘Oh, look, these planets are out, or the Moon is in this phase, or look at the Milky Way,’ but there’s another relationship that comes along with it that’s more of a psychological relationship.

When I’m in a place that doesn’t have stars, it’s like they’re gone, and therefore, there’s no more information, and there’s no greater universe. There’s no infinite anymore.

RB: I remember talking to you when you were coming through Colorado Springs a couple years ago now, and you were about to go on your trip, which became this book. I wondered how you became inspired to write this. Were you concerned, that when you go places that you often don’t see the stars? Or was it more like, I want to write about this so that more people can understand what they’re missing?

CC: Yeah, it’s about the missing part. I think there are so many people who don’t have access for one reason or another. They just don’t live in a place where that sky is available, or they don’t often get to a place like that. I wanted to write this book to transport them out to a darker sky so that they could see what it’s like. And that, to a degree, comes from back when I was younger, and I was taking kids from Los Angeles into the backcountry, into the desert 200 miles from LA. I would take them out for a few nights at a time, working with with an outdoor company. I remember witnessing their response to the sky—kids who, in many cases, had never seen stars, or had not not seen them in that kind of profusion. And seeing how some were frightened by it, which impressed me. I was going, wow, you guys are actually responding to knowledge that you didn’t have before. That’s what I want to be offering readers who don’t have access to it. I wanted to make clear in in this book that the sky is always present, and that it’s our activity that erases it, and that as soon as that activity ends, the sky is right back. And you can see everything.

RB: One thing that struck me in this book is that it’s not about absence. A dark sky is not about the absence of light, but the presence of everything. And that is kind of counterintuitive. We’re really conditioned to think that darkness is bad or scary, and we need a lot of light to see, but it’s actually a state that is more natural. A night sky is not an absence of light, but the presence of the universe. I appreciated that on a personal level, but it is sort of a reframing, and I wonder how much you thought about that in writing the book.

Available at your local independent bookseller or at Bookshop.org

CC: I don’t know if it’s a unique way of seeing it, but because I’ve spent so much time in that sky, I’ve thought about it a lot. And so when I’m writing about it, I’m just trying to take my natural experience and my proclivities, and put them on the page and, in a way, just remind the reader what they’re already thinking about.

That’s how I write. I do organize, but I also just rely on my innate relationship with the subject, and let that go where it wants to go. I’m kind of just throwing it down on the page and seeing what pops and and when I come across a truth, like the presence versus absence, that is maybe not something that I consciously think about, but then when I see it, when it comes out in a a narrative, I go, there it is, and then I run with that. It sort of organically develops, which is laborious.

RB: From my point of view, as somebody who writes about astronomy, the night sky—the actual subject that is being studied by the people that I write about—is harder to access now. And yet I feel like knowledge of that is finally breaking through in a way that it hadn’t before. I think this is a well-timed book for that reason. Why do you think that is? Are people more concerned about this issue now, or it’s more obvious here, because we can access darker skies in the West, and people who are traveling here and maybe moved here because of the pandemic have now noticed it?

CC: Yeah, maybe the pandemic and people moving to rural places increased it. I hadn’t really thought about that, and I could really see that; people were looking up going, ‘Oh my god, this really does affect you. Why weren’t we feeling this way before?’ I also think it’s that things have grown notably brighter in the last two decades, especially with the advent of LEDs. I think that they’ll ultimately lead to better skies, but the last few decades of experimentation with them has brought in a lot of cheaper, more efficient lighting, but lighting nonetheless. We’ve actually been mistaken with how we’ve been using light, and I think LEDs were part of that—they became so available, we started throwing them out everywhere so that we could see everything on the ground. And now we’re going, ‘Okay, let’s put some nuance into this, and let’s figure out how to engineer our lighting so that we can preserve a sky.’ We’ve come to a recognition of what we’re losing and how much we can control that, and how much we can change it, which maybe 20 years ago wasn’t as obvious.

RB: In a lot of reviews and the early praise you’ve had so far, a lot of people have called your book mournful and also hopeful. And that’s very much how I felt too. It was an elegy, but also a hopeful path forward. And I think that is appropriate for the current moment. There’s a lot to mourn, but if we can hold on to some hope, maybe it’s not all lost. We are very easily able to see what is being lost and what is being destroyed, but we can also see a way out of it that’s maybe not as difficult as we might think. Am I reaching here, or is this an appropriate analogy?

CC: That feels very true to me. I think that mourning and hope go hand in hand, because mourning is a recognition of of what is being lost. If we were just allowing it to go, and not grieving the loss, that, to me, would be the worst case scenario.

I think mourning is part of the necessary process of turning things around. When I originally was plotting the trip that made up this book, the big question was, should I start in the dark and go to Las Vegas, or start in Vegas and go to the dark? Originally, I was doing it the other way around. I was going to start in the darkness and and build up and say, this is where we’ve stolen the night sky, and this is where it is lost. And then I realized, oh, that’s not where I want this to go. I want this to head the opposite direction. I want to start with the grief of what is going away, and say, ‘Actually, it’s not gone. It’s right over there. And let’s go look at it over there.’ That way, I can look back at Vegas and say, this is where it has been taken away, but this is actually a small place compared to the darkness around it. And so there’s a great hope here. The sadness that comes with it is an active sadness, and it compels you to do something to bring it back.

I think that is true for a lot of things. There is so much that I feel like we’re losing right now that we are going to have to fight to hang on to. And that fight is necessary.

Rebecca Boyle is a science journalist and author in Colorado Springs. Her first book, Our Moon: How Earth’s Celestial Companion Transformed the Planet, Guided Evolution, and Made Us Who We Are, is the winner of the Los Angeles Times Book Prize, was longlisted for the National Book Award in Nonfiction, and was named a best book of 2024 by the New Yorker, Smithsonian, Amazon, and many others. It is out in paperback on June 3.

Click here for more from Rebecca Boyle.