Liminal spaces

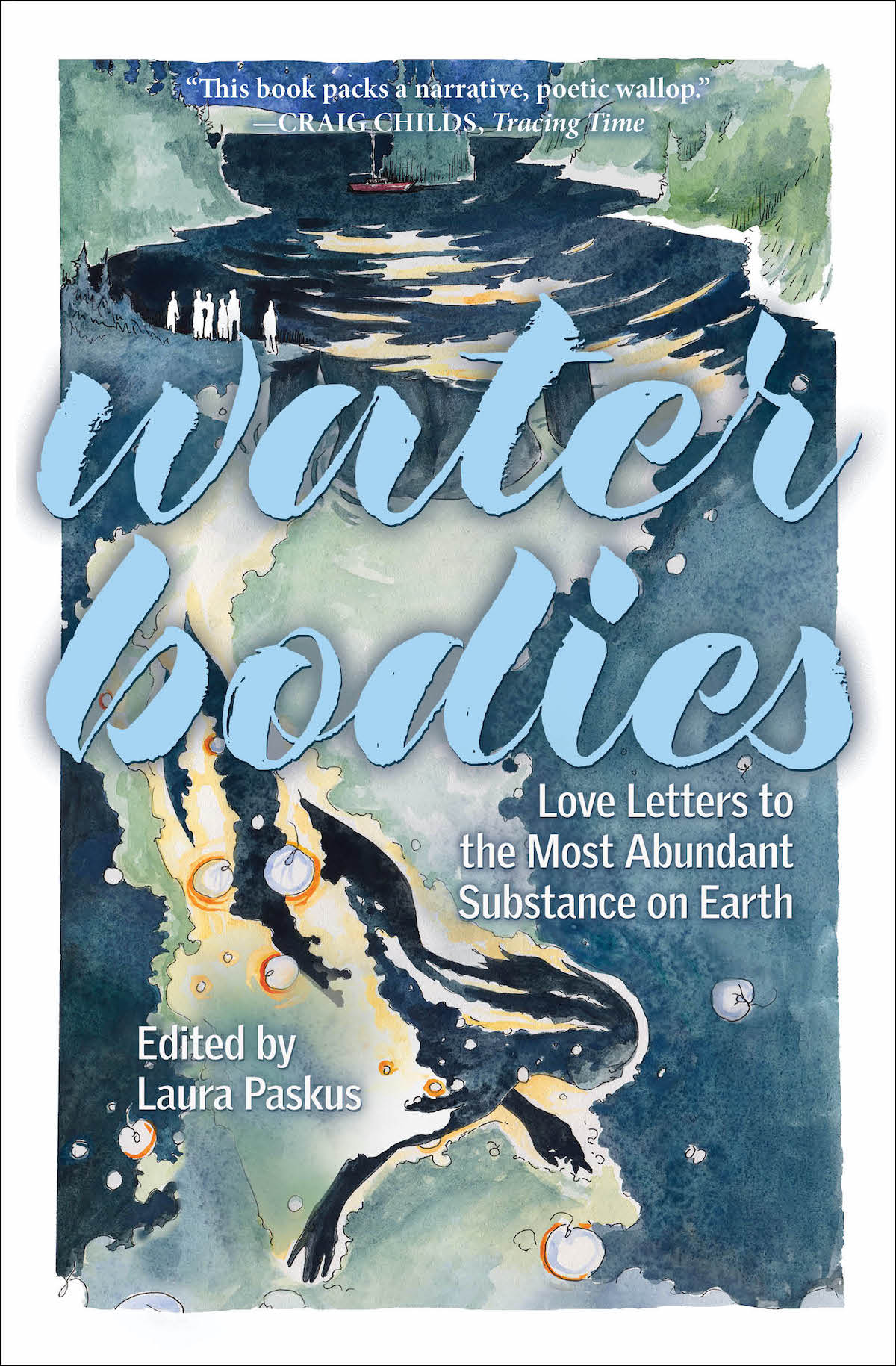

Exploring humanity’s relationship with water in Water Bodies

Exploring humanity’s relationship with water in Water Bodies

“In union with water, we cry, we are born, we survive.” —Laura Paskus

In her introduction to Water Bodies, a slim but gorgeous anthology of nature writing and poetry, editor Laura Paskus asserts that “waters are creatures themselves—entities with desires, dreams, and stories.” This claim ties the pieces within the anthology together, each in part an investigation of the role water plays in our cities and communities. The pieces also explore natural and cultural history, individual relationships with nature, and the uncertain heaviness of our collective future. Paskus, an environmental reporter based in New Mexico, includes 16 diverse writers—five of whom are from Colorado—who together discuss the complicated relationship between water and the American West.

Laura Paskus, editor of Water Bodies

Thematically central to the anthology is the concept of belonging: how some still belong to land that was taken from them, how they worship and remember their sacred places and how the landscape shaped their understanding of the world. In one piece, a personal essay called “The Water Carrier,” Regina Lopez-Whiteskunk details her formative experience of becoming the water carrier for a peyote ceremony. At nine years old, she is given this responsibility with the understanding that it is more than simply carrying water. Instead, it represents her movement from childhood into adulthood: “I was taking my position as a water guardian, voice, taking my position as a Ute woman in my family. Little did I know this would be the first of many lessons water would teach me. In prayer and sacred position, the water speaks.” The morning of the ceremony, in the shadow of Ute Mountain in southwestern Colorado, on the land where her family has lived for generations, she steps into her place as a keeper of knowledge.

In contrast, the anthology also follows those who have drifted from place to place, who waited well into their adulthood to find a place to land. Professor Maria Lane discusses this in her essay “A Long View Over Albuquerque.” She considers, through the lens of her own experiences, the complex power relationships between Indigenous spaces and colonial ideals. She considers herself a “placeless settler,” a product of the westward expansion that disrupted (and continues to disrupt) the tangible natural world. She says, “I never thought too deeply about my own placelessness and participation in settler colonialism until I began engaging with UNM students whose lives are anchored by ancestral and generational connections to New Mexico landscapes.” This is on her mind as she sits on a high desert hill, staring at Albuquerque spread out below in a dazzling nighttime show of lights. But she picks out the dark ribbon of the Rio Grande, the black stretch of cottonwood trees beside it, the shadows within the city that are parks or open space. It is a tapestry that depicts nature and civilization combined, the latter unable to exist without the former.

Perhaps most intriguing about this anthology is the way it embraces conflicting ideas. It lays them out not only as binaries, but as spaces connected by a spectrum of countless colors. In addition to belonging vs. placelessness, the essays explore past vs. future, joy vs. agony, apathy vs. responsibility, tradition vs. innovation, loneliness vs. connection, elation vs. fear. This confliction mirrors that of water itself. Water gives life; water destroys life. Too little water means drought. Too much water means flood. Water, like the tenuous connection between humanity and nature, is most beneficial when balanced. In these changing times, the problem is that water is out of balance. Throughout the world, humanity tries to be stronger than nature. In the nighttime tapestries of our cities, those dark spots of wilderness are shrinking. Early in Water Bodies, the poet Fatima van Hattum addresses this in a haiku titled “Gold King Mine Spill:

that of water itself. Water gives life; water destroys life. Too little water means drought. Too much water means flood. Water, like the tenuous connection between humanity and nature, is most beneficial when balanced. In these changing times, the problem is that water is out of balance. Throughout the world, humanity tries to be stronger than nature. In the nighttime tapestries of our cities, those dark spots of wilderness are shrinking. Early in Water Bodies, the poet Fatima van Hattum addresses this in a haiku titled “Gold King Mine Spill:

The same. They always

come for. Water is life,

but gold is prettier.

All told, this anthology asks more questions than it answers. What must we do about the water crises we are facing? Who should be responsible for the flow of water across the western region of the United States? Which commodities (swimming pools? lawns?) should we let go for the good of all? And, in the process of developing answers to these questions, how can we remain connected to one another, to our foul and honorable histories, to nature itself? Is it possible to dismantle the concrete foundations of our societal structures and open ourselves to wildness?

While Water Bodies does not answer these questions, it is not a bleak read. Instead, it is full to bursting with wonder, with essays and poems that describe the everyday beauty of the sea, the snow, the streams. My personal favorite is a graphic poem called “Surfacing” by Sarah Gilman, in which she represents, through words and pictures, the secret world of water underground. She writes:

“After thousands of feet of descent, and dozens of miles of traverse, streams and rivers born in the dark break free and tumble from the Grand Canyon’s walls. Once, an author friend climbed into the rushing mouth of the largest of these falls, hundreds of feet up a cliff. He and his companion wedged their way through tunnels and swam wide caverns for a quarter mile until the chill turned them back. Later, he wrote that he remembered the silence of the spring’s deeper chambers most of all. It felt like the beginning of the world.”

We interact with water every day of our lives. But there is still much for us to learn, to feel, to do. And while we are learning and feeling and doing, we must never forget the wonder—the power—of the element responsible for all life on Earth. That is what Water Bodies helps us do.

While Marissa Harwood was born in Omaha, Nebraska, she moved to Colorado when she was four days old and considers herself a native. She grew up in the shadow of the Rocky Mountains and spent much of her childhood camping, hiking and building forts in the woods. She earned a BA in English and a Secondary Teaching License from the University of Colorado at Boulder. Later, she attended Western Colorado University and earned an MFA in genre fiction. She has taught English at three K-12 schools and two Colorado colleges. Currently, she lives in Greeley, where she teaches high school, plays with her daughter (a true CO native) and reads a lot of books. She hopes to earn a doctorate in the near future.

Click here for more from Marissa Harwood.