Drinking with Maigret

Good to the last drop—author Alan Prendergast on the pleasures of reading Georges Simenon’s 75 Inspector Maigret novels

Good to the last drop—author Alan Prendergast on the pleasures of reading Georges Simenon’s 75 Inspector Maigret novels

I was on the final pages of my fourth Maigret novel—translations of Georges Simenon’s classic series about an ingenious French detective—when I realized that I was going to have to read all 75 of them. Yes, it’s a commitment, but so is binge-watching Bad Sisters or tucking into a prix fixe seven-course meal—not something you’d want to do every day, but a special indulgence that you know you damn well deserve.

My obsession started with the purchase of a stack of paperbacks at a thrift store in Carbondale. I was on vacation and in search of beach reading. Jules Maigret, the large, pipe-smoking chief inspector of the Paris Police Judiciare, seemed to be what I was looking for, a stock character from a well-worn genre. Like Holmes, Poirot or Nero Wolfe, he was brilliant, eccentric, jaded and brimming with mannerisms.

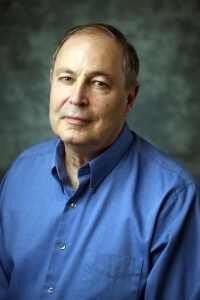

Alan Prendergast

But the Maigret novels aren’t merely puzzles to be solved. The question of who bludgeoned Colonel Dijon in the conservatory takes a back seat to many other questions. The books are nuanced, sharply rendered inquiries into family secrets and seething resentments, long-simmering grievances of class and privilege, insatiable greed and thwarted lust and misdirected rage—in short, what drives people to do terrible things and what, if anything, shames them. I knew I was hooked when I reached the last chapter of Liberty Bar, in which the inspector attempts to summarize his latest case to his remarkably patient wife, always referred to as Madame Maigret, while the couple savor a lunch of salt cod in cream sauce.

The case concerns an Australian expat, bored to death living on the Riviera with his mistress, who finds a “fat, kind woman to drink with him” in a seedy bar in Cannes. That relationship blossoms—and turns deadly when the man takes up with his new love’s protégé. The murder will never be officially solved, Maigret explains, because the man’s powerful family wants to hush it all up; it is “a poor little love story with a rotten ending.”

Rotten indeed. But Maigret makes an extraordinary and oddly compassionate effort to win the trust of the scorned woman and retrace the dead philanderer’s role in his own destruction. The inspector’s quest to divine the hidden dynamics of motive transforms a tawdry whodunit into a tragic amor fou.

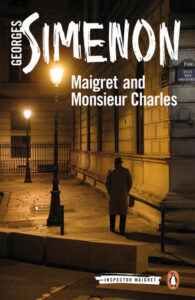

Crimes of passion are a hallmark of the Maigret series, from Pietr the Latvian, first published in serial form in 1930, to the last entry, Maigret and Monsieur Charles, published in 1972. In 2013 Penguin Books began to reissue the entire series in new translations, a quixotic project that wasn’t completed until 2020. Yet the Maigret novels represent only a modest portion of the copious output of their creator, Georges Simenon. Born in Liège, Belgium, Simenon began writing professionally in his teens and published around 400 novels by the time of his death, in 1989, at the age of eighty-six.

Georges Simenon

Simenon rarely spent more than two weeks writing a novel. Although the Maigret books paid the bills, he preferred to be known for his “serious” novels, his romans durs—tough-minded studies of psychologically tortured and often doomed protagonists. Several of these titles, including Dirty Snow and The Man Who Watched Trains Go By, can hold their own with the work of James M. Cain, Patrick Hamilton, Patricia Highsmith, or any other mid-century noir writer now fussed over by academics. Some of them are so steeped in grim, no-exit misery that Maigret’s forays into deadly domestic follies seem almost chipper in comparison.

Admittedly, the plots of some of the Maigret books are too elaborate by half. The director Jean Renoir, keen to make a movie out of Maigret at the Crossroads, reportedly offered the author 50,000 francs if he would appear in the film and explain what was going on. (Simenon refused.) A surprising number of the mysteries revolve around ordinary citizens who are leading double lives, or once-respectable professionals who turn up as dead vagabonds; many people, it seems, want to be somebody else.

But plot was never the main draw. The energy of the stories comes from Maigret’s determination “to understand and not to judge,” to fathom the torments that produced the crime. More often than not, he must immerse himself in some tight-knit neighborhood or subculture—the demimonde of club girls and hustlers in Montmartre, the insular world of the bargemen on France’s rivers, the staff and guests of a snooty hotel, the petty personal rivalries in a backwater town—in order to ferret out the killer.

It’s thirsty work, compelling Maigret to stop at various decrepit bars and well-tended brasseries, soaking in the atmosphere as well as a prodigious amount of Calvados, pastis or the local second-best white wine. Sometimes the excursion leads to an all-night interrogation at headquarters, an opportunity for Maigret to send out for sandwiches and beer while breaking through the façade of lies and evasions.

There’s something deeply comforting about these rituals of the investigation—more so now, perhaps, than when the books were first published. They are a testament that, no matter how isolated we may appear to be in our own private worlds and polarized camps, it’s possible for a determined, empathetic listener to break through the barriers and discover what moves us, our dreams and fears and darkest desires.

It helps that these revelations are served up in a rich broth of nostalgia. Trips to the provinces remind  Maigret of his own small-town boyhood; a hearty choucroute (sauerkraut and sausages) is his madeleine. The detective prefers a wood-burning stove to central heating and deplores many other incursions of modernity, from soulless new housing developments to an expanding bureaucracy that threatens his autonomy. World War II doesn’t even receive a mention in the world of Maigret; it’s as if the German occupation never occurred, never interrupted the detective’s fond memories of a city and a time that was rapidly disappearing even when the series began.

Maigret of his own small-town boyhood; a hearty choucroute (sauerkraut and sausages) is his madeleine. The detective prefers a wood-burning stove to central heating and deplores many other incursions of modernity, from soulless new housing developments to an expanding bureaucracy that threatens his autonomy. World War II doesn’t even receive a mention in the world of Maigret; it’s as if the German occupation never occurred, never interrupted the detective’s fond memories of a city and a time that was rapidly disappearing even when the series began.

Simenon had a much messier life than Maigret. He was notorious for his lurid and sometimes violent love affairs, and was accused, on tenuous evidence, of being a collaborationist during the war, prompting him to move to the United States for several years. (One of Maigret’s adventures is set in New York City, another in Tucson.) But the detective and the novelist may have more in common than it might appear; they are both our escorts to a secret world of heartbreak and loss. In Félicie, while engaged in a particularly exhausting, hard-drinking battle of wits, Maigret “has the feeling that the damned job he has chosen to do makes him lead other people’s lives instead of quietly living his own. Fortunately, in a few years he will be able to retire.”

Retirement comes to us all, even if the job makes us thirsty for more. Last week I finished the only remaining Maigret title on my reading list, which is a bit like admitting that there is not a drop to drink left in the house.

Click here for more from Alan Prendergast.