An author’s life and work resurrected in Technicolor

A biography of Sanora Babb, whose contribution to Steinbeck’s Grapes of Wrath went unrecognized

A biography of Sanora Babb, whose contribution to Steinbeck’s Grapes of Wrath went unrecognized

Poet and novelist Sanora Babb died in Hollywood on December 31, 2005, at age 98, just one year after her first but not only novel, Whose Names Are Unknown, was finally published by the University of California Press. She’d finished writing it 66 years earlier.

Iris Jamahl Dunkle

The book, titled after those whose names remained unrecorded on death certificates, recounted a farm family’s struggle to survive in Depression-era Dust Bowl Oklahoma and in the California migrant labor camps they’d fled to in search of work. Babb wrote it partially based on her own life, and partially based on work she did volunteering for the Farm Security Administration (FSA), which was established as part of the New Deal to combat rural poverty. Her book, originally scheduled to be published by Random House, was delayed and then cancelled due to the overwhelming success of John Steinbeck’s now-classic second novel, The Grapes of Wrath. Published in 1939, Grapes to date has sold more than 15 million copies and has this dedication: “To Carol who willed it, and Tom who lived it.”

Carol was Steinbeck’s wife. The latter was Tom Collins, a friend of Steinbeck’s and a supervisor of Sanora Babb’s at the FSA. Collins had made copies of Babb’s field notes and gave them to Steinbeck without Babb’s permission or knowledge. Though not precisely plagiarism, Steinbeck took Babb’s work and spun it into an extremely lucrative and influential triumph. Grapes was adapted into an acclaimed film by John Ford in 1940 and had much to do with Steinbeck’s Nobel Prize for Literature in 1962.

Babb received no mention at all in the book, and no compensation for her work that contributed to its culmination.

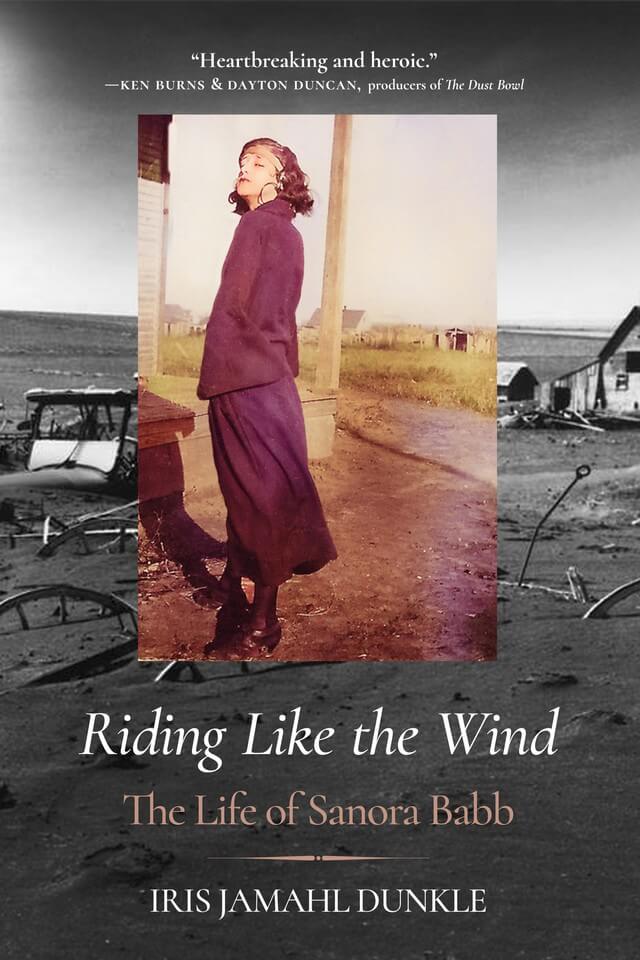

Biographer and poet Iris Jamahl Dunkle describes with an abundance of empathy this and many other dramatic aspects of Babb’s life, including multiple highs and lows that spanned nations in her 2024 biography, Riding Like the Wind: The Life of Sanora Babb. Babb was born near what is now Red Rock, Oklahoma, and superseded quite real and unavoidable odds stacked against her; female and poor she was unable for the first decade of her life to access basic education. Her most likely fate, in fact, was exactly that of those nameless people honored by her first novel. The reality she created with her life was quite the contrary. (An October Atlantic Monthly review of Riding Like the Wind was titled “The Woman Who Would be Steinbeck.”)

Babb learned to read when she was a young girl by examining newspapers plastered on the dugout walls of one of her family’s homes, a one-room pit house carved out of the earth near Lamar, Colorado. Her grandfather taught her math with a stick he used to draw in the dirt. The dugout was heated by burning wood when available and stinky cow dung when it wasn’t. There, Babb was semi-raised by a father who was a semi-professional gambler and a semi-professional baseball player and a mother who baked goods to be sold at a bakery in which she and her husband had a stake.

Babb’s father had bought 160 acres of eastern Colorado land for $750 in 1914 despite the fact that he could have gotten it for free through the Homestead Act of 1862 had he at least attempted to farm it for five years. This was just one of many rash decisions that nearly killed his family through starvation and living without basic necessities. Babb, meanwhile, had been taught to mark her father’s playing cards with small pen blots or cutouts, unwrapping and rewrapping them in the plastic they came in, so they were cleverly discernable from their posterior sides. The Babb family arrived in Elkhart, Kansas in 1917 via wagon, enabling Babb to attend school regularly. There, she began to write, and got her first job writing for a newspaper, the Garden City Herald.

Several of her articles were distributed by the Associated Press. In 1929, she moved to Los Angeles to work for the Los Angeles Times. The stock market crash that same year, however, caused her job offer to be rescinded. Babb was occasionally homeless during the Depression, sleeping at times in Lafayette Park. She eventually found secretarial work with Warner Brothers and wrote scripts for radio. She was a member of the U.S. Communist Party for 11 years and visited the Soviet Union in 1936.

Babb had committed to memory the flora and fauna that she observed as a young child, and those plants and animals reappeared in many of the stories and poems she would later write.She also wrote of some of the more remarkable events in her life. Chief Black Hawk of the Otoe-Missouria tribe had given Babb hand-sewn moccasins following an event when her young pony darted off following a nearby gun shot. “You did very good staying on your new pony even though he was running like the wind! Your new name is Cheyenne, Riding Like the Wind,” he informed her.

her life. Chief Black Hawk of the Otoe-Missouria tribe had given Babb hand-sewn moccasins following an event when her young pony darted off following a nearby gun shot. “You did very good staying on your new pony even though he was running like the wind! Your new name is Cheyenne, Riding Like the Wind,” he informed her.

Though Babb didn’t start school until age 11, she ultimately graduated valedictorian of her high school. This honor, however, was never publicly bestowed due to community complaints regarding her father’s longstanding gambling habit. Babb finally found a job posing nude for students at the Otis Art Institute in Los Angeles for 40 cents an hour, but she fainted from hunger during a session and was promptly fired. “We were so busy trying to survive we had no idea we were storing up experience,” Babb wrote in a journal. “What I remember most is the grim humor, even laughter and sometimes we sang together, very low, at night.”

Babb wrote war stories that rang hollow due to her lack of experience. But two other books, The Lost Traveler (1958) and An Owl on Every Post (1970), a Dust Bowl novel and a memoir, respectively, borrowed details from her early life more accurately. In her poem “Coute Que Coute,” Babb declares with the unbridled verve of Marie Antoinette that she will “eat my cake and care not / About the hungry days…I shall / Walk wisely down lean ways,” somewhat foreseeing her own life that would culminate in the Hollywood Hills, where she finally settled.

Romantic entanglements and friendships with various creative men further peppered Babb’s life, adding to its richness and the actualization and obfuscation of her own creations. Starting in 1932, Babb had a long friendship with Pulitzer Prize- and Academy Award-winning writer William Saroyan that was for him an unrequited romance. Ralph Ellison, writer of Invisible Man and winner of the National Book Award in 1953, was a romantic partner of Babb’s from 1941 through 1943. In 1937, she married Chinese American cinematographer and 1956 Academy Award-winner James Wong-Howe in Paris due to anti-miscegenation laws in the United States. They legally wed in America in 1948, when mixed-race marriage finally became allowed. At that point, they ceased their years of living in separate apartments in the same building, having pandered to a “morality clause” in Howe’s contracts.

For all the fame and artistic talent that enhanced Babb’s years, Dunkle brings her story most powerfully to life by recounting instances of basic survival. Babb’s mother Jennie was told by her town doctor, Dr. Verity, that she ought to drink more milk to ensure that her forthcoming daughter wouldn’t leach the calcium from her own bones. To do this, Jennie dressed herself and her other two children in freshly ironed dresses, carried “a shiny gallon pail for milk,” and set out with a cart on a summer day past her own family’s broom corn farm to the lusher Haupman farm with alfalfa fields four miles away, where a water source was available to irrigate the crops. There, they drank their fill of buttermilk and ate as many thick slices of buttered bread as they could. As evening began to fall and storm clouds gathered, Mrs. Haupman declared that suppertime was nigh, accepted a dime for a bucket of milk, and brusquely sent the Babbs on their way. The road home turned into a slog of wet mud pelted by lighting and torrential rain. Walt set out looking for them, and arrived with a wagon. He ordered an exhausted, extremely messy Jennie to drop and dump the milk, and yelled at her ferociously for having ventured out in such terrible weather. They made it home and, as Dunkle puts it, “By the time they got settled inside, the storm had miraculously passed and the sky looked down on them with a big blue grin, as if nothing had happened and they’d imagined the whole thing.”

Click here for more from Sarah Valdez.