In defense of shrubs

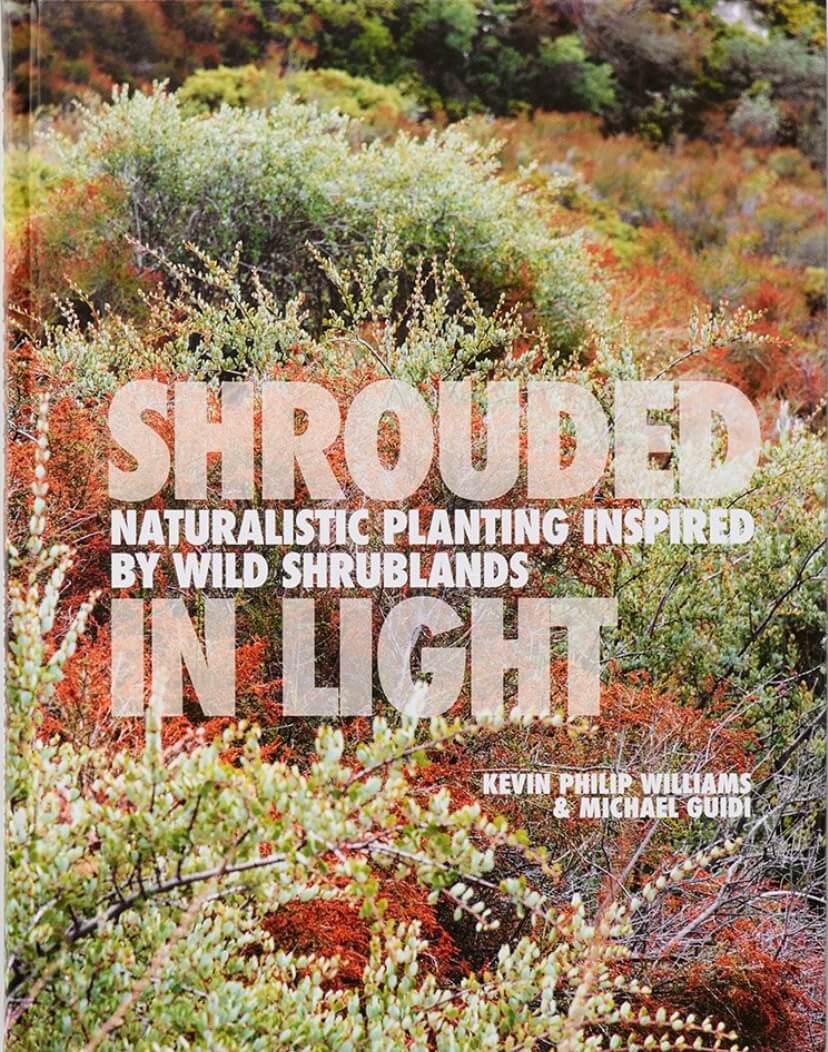

Filled with color and light, this gardening book reimagines the Colorado garden, inspired by wild shrublands

Filled with color and light, this gardening book reimagines the Colorado garden, inspired by wild shrublands

When I first sunk my spade into a sizeable chunk of East Anglian soil, it was to plant shrubs to give my new garden a framework. The hedges I planted as screens and backdrop included a dark green yew hedge, and a tapestry hedge of all sorts of evergreen and deciduous flowering, berrying and autumn coloring material. Being an “English garden,” there was lavender and boxwood hedging too. Only then did I start filling in perennials, bulbs, grasses—the usual suspects.

Kevin Phillip Williams and Michael Guidi

Twenty-five years later, coming to terms with my Colorado gardening efforts, I have renewed my affair with shrubs, wooed by Shrouded in Light: Naturalistic Planting Inspired by Wild Shrublands, a book devoted to the wondrous textures, colors and fabric this plant group brings to a garden picture.

Written by Kevin Phillip Williams and Michael Guidi, the former an Assistant Curator and the latter a Horticulturist, both at Denver Botanic Gardens, the duo drew their inspiration, as the subtitle says, from the wild. The significance of the title is owed to a landscape painting by Sean McNamara, a digital artist based in North Carolina. His painting illustrates nature bumping up against the man made, organic vs inorganic, and that is pretty much what the authors are expressing in this generously sized (10 in x 14 in), 240-page, spectacularly illustrated book.

The introduction, by Nigel Dunnett, the leading voice in the UK’s naturalistic garden movement, lays out the argument in defense of shrubs and their place in the ‘naturalistic’ landscape movement. This movement has been dominated by herbaceous perennials and grasses; shrubs have been underrated, dismissed as ‘scrub’ or as ‘brush’–a non-descript vegetative cover beneath a tree canopy or simply filling the space where more desirable plants might grow (or not, depending on conditions).

Digging into the book, Williams notes when he first encountered the “Great Sage Brush Sea,” which spans most of the Intermountain West and is the largest terrestrial ecosystem in the lower 48 states. “My mind melted,” he writes. “… My veil was being shredded” A little hyperbolic, but I get it; that’s pretty much the same way I felt as I drove from Colorado Springs to Santa Fe through the San Luis valley.

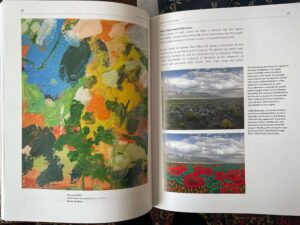

The inclusion of contemporary art images is meant to inspire and inform design decisions.

This book, then, focuses down deep on the southwest’s shrublands, an integral part of what is one of the earth’s four steppe regions. In this way, this book is a companion volume to Steppes: The Plants and Ecology of the World’s Semi-arid regions. I will testify that even if you live and garden outside a steppe region, both these books are worth reading and referring to as your garden life evolves, as it must in these strenuous climate-change times, to take more account of the interconnectivity of life on earth.

Most of us who garden ardently require little convincing on this, but the chapters devoted to learning about the eco-diversity of shrublands expands on this theme: The section “Fruits” is sub-sectioned into Global Weirdness, How Shrubs Exist, Leaves, moving onto a small photo album of Flowers, then Brush Beasts of Shrublands from Tibet to the California coast, all making the point that shrubs shape the landscape pretty much everywhere you look if you take the time to see.

The inclusion of contemporary art—drawings, paintings, conceptual pieces—throughout the book made the case for me. “Gardens are full of non-linguistic, representational communication that we use to create a dialogue with the non-human world.” Yes, we do. “…we garden indexically.” I had to look that one up; the text does every so often give the reader pause to puzzle over what exactly the author is getting at. Creating landscapes/gardens that include shrubs, they write, “We use the shrub as an icon, an emoji worth a thousand words.” I’ll have to think about that the next time I add a shrub to my burgeoning naturalistic, somewhat brushy garden.

Part 2, “Seeing Shrublands,” looks at Model and Alternative Shrublands that shape the earth’s natural landscape, and from which lessons  learned can be applied in the home garden. Part 3, “Making Shrubscapes,” takes us to the practical heart of the book. I’m all for having a good think, but process and doing is more to the point for me and for most gardeners. The authors caution that “[r]eplicating a natural landscape is impossible and will not produce a garden with a satisfying or feasible future.” What we can do is study as we would a painting, the composition, textures, colors and forms of the natural landscape and translate it into something that is recognizable as a garden.

learned can be applied in the home garden. Part 3, “Making Shrubscapes,” takes us to the practical heart of the book. I’m all for having a good think, but process and doing is more to the point for me and for most gardeners. The authors caution that “[r]eplicating a natural landscape is impossible and will not produce a garden with a satisfying or feasible future.” What we can do is study as we would a painting, the composition, textures, colors and forms of the natural landscape and translate it into something that is recognizable as a garden.

Again, the art tipped in among the garden images drives this point home, along with analysis of actual gardens that take their aesthetic from the regional steppes of North America.

In Denver, for example, SummerHome is an infill garden created in a city neighborhood to fend off development of a lot-line to lot-line McMansion on the site of a tear-down bungalow. Working with a small team from Denver Botanic Gardens, Williams turned the naked lot into a richly colored and textured shrubland composition. The footprint of the garden was inspired by a graffitied phone box in Ljubljana, Slovenia; the planting echoes where the short grass steppe meets the desert southwest. (It’s a dream to sit within its borders, entertained by the wildlife it attracts. Bees love it!)

This wouldn’t be a 21st century garden design book if it didn’t include a number of what the authors have dubbed “Cyberpunk Shrubscapes.” It’s a rather tongue in cheek title, intended to be purely inspirational, showing gardens that have been digitally created by AI (Artificial Intelligence) for an imaginary place called “Cyberspace.” It seems simple enough in theory; all you need is a computer and a prompt, a short written description of what you want AI to generate visually. It really does tempt me, a dyed in the wool Luddite, to have a go: my prompt might be ”an Italianate garden using trees and shrubs native to the Front Range.”

Just imagine!

Ethne Clarke is the author of a number of best-selling books on practical gardening, design and landscape history, published in England, the USA and Europe. Since 2016, she’s been a contributing editor for Hartley Botanic’s online magazine, and prior to that was Editor-in-Chief of Rodale’s Organic Gardening magazine. Ms. Clarke holds a Master of Philosophy from the faculty of Art and Design, De Montfort University, Leicester, England, and has lectured around the world in her subject areas.

Click here for more from Ethne Clarke.