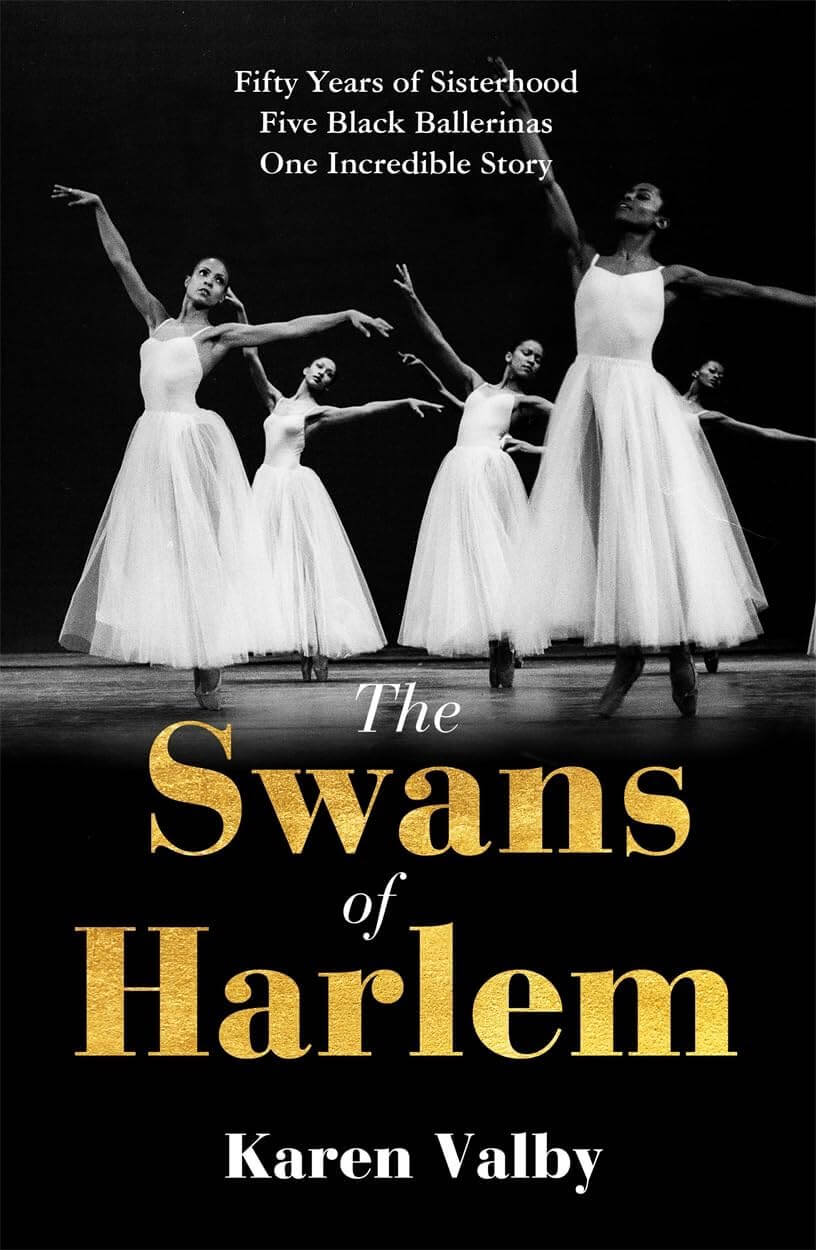

En pointe before Black ballerinas were recognized

The Swans of Harlem, accomplished classical dancers, come to light

The Swans of Harlem, accomplished classical dancers, come to light

Ballet shoes were only available in pink in the early 1960s—a subtle but clear indication that there would be no need for pointe shoes of other colors or featured dancers of skin tones other than white in the classical ballet world.

Karen Valby’s Swans of Harlem details the struggles and successes of five women of color who broke barriers in ballet with their persistence, formidable talent and grace. Post-Civil Rights Movement, Lydia Abarca, Gayle McKinney-Griffith, Karlya Sheldon, Sheila Rohan, and Marcia Sells, five intrepid girls, became the Black Swans of the Dance Theatre of Harlem, a troupe which startled the classical ballet world with its beauty and art.

Karen Valby

Even as young girls, the Swans loved dance and joined others at the barre in classes. Most were the sole persons of color in their classes and were seldom given roles to perform though they diligently arrived at auditions in their pink tights and toe shoes. As Sheila Rohan said in an interview when Shelton spoke of touring to find a place in a ballet company, “Didn’t our mother tell you that no white company was going to take any Black ballerina?” Sheldon danced with a white company from age twelve. Yet, when cast in The Nutcracker, she was seen as a “dirty snowflake” by a young member of the audience.

Each of the five dancers featured in Swans of Harlem found opportunity with the Dance Theatre of Harlem, the dream of danseur Arthur Miller who founded the company in 1969 and engineered its success. Despite constant fund-raising and occasional penurious times, Miller was determined. “Tell me I can’t, and I’ll show you I can,” he said.

Dance Theatre of Harlem offered Black dancers rigorous training eight hours a day across six-day weeks. Although several of the Swans had enrolled in colleges or Julliard, their training at the dance theatre made pursuing degrees impossible. Arthur Miller, a taskmaster who restricted hair to discreet buns, vetted boyfriends and gave strict fashion criticism, sought talent everywhere, but he decreed that Dance Theatre of Harlem was an ensemble, giving few dancers a singular focus as soloists.

First of Miller’s notable Swans was Lydia Abarca, raised in the projects and starstruck as a child. Once she toe-danced into the Dance Theatre of Harlem spotlight, she became a Dance Magazine cover-girl in 1975, the slim perfection of a prima. Gayle McKinney-Griffith became not only a principal dancer but also the company ballet mistress. Organized and a capable trainer, she also captured dance notation as the choreographers generated new works.

Sheila Rohan was a 27-year- old mother of three, a country girl from Staten Island who worked tirelessly to be an outstanding and reliable member. At age ten, Marcia Sells had transitioned to pointe work. “It is like foot binding,” she said. “This tight little box squeezing your feet. It’s all blisters, and bunions, and losing your toenails.” During performances, the pointe shoe must bear the ballerina’s entire weight. Years of exercise and suddenly “you feel light, Sells said. “Oh my gosh, you are a ballerina.” She joined the company at age 16.

Colorado’s connection with Dance Theater of Harlem was Karlya Shelton, a young girl who dreamed of dancing from her Denver home. She had already received awards and represented the United States at the prestigious international Prix de Lausanne competition in Switzerland by the time she joined Dance Theatre of Harlem. At a teen, she came to New York, stayed with family and religiously attended the dance theatre’s training. Younger and shorter, Shelton brought to the ensemble arm strength and the capacity to leap two feet higher than the others. Shelton is long remembered for her flawless performance in 1983s Equus.

Working during a ballerina’s short optimum, these women of disciplined perfection danced abroad before the Queen; for Presidents, Mick Jagger and Stevie Wonder; had seasons in downtown NYC; and worked for Alvin Ailey, Bob Fosse and Balanchine. They found roles onstage in The Wiz, and danced atop the piano in the film. They trained others and led workshops. Later, they found less athletic jobs while facing cancer, alcoholism, grief, loss of colleagues and recovery. They never forgot their 50-year friendship.

Until the 1990s recognition of Misty Copeland, there was no national recognition or awareness of previous prima ballerinas  of color. History had erased the Swans’ successes until Valby wrote a feature on the 152nd Street Black Ballet Legacy Council that appeared in the New York Times.

of color. History had erased the Swans’ successes until Valby wrote a feature on the 152nd Street Black Ballet Legacy Council that appeared in the New York Times.

Now quite senior, these women had formed the Council to remember and celebrate but also to open doors, to encourage aspiring young people to classical dance, and to recognize the lineage of success. The Swans credit so many with their success: the Dance Theatre of Harlem team of trainers, musicians, designers; Arthur Miller; other Black performers and dance theatre donors. As well, they revere their strong, handsome, and reliable male partners who worked just as hard, who lifted but never dropped them and who suffered the AIDS epidemic disproportionately.

Valby spent three years meeting these women, sharing with their families and learning of their accomplishments. She structured her book in three acts: beginning careers, leaving the Dance Theatre of Harlem and focusing on the future. Readers unfamiliar with ballet vocabulary may stumble with terms beyond pirouette, plie, arabesque, and pas de deux but will be intrigued with the black-and-white photos that capture the Swans’ elaborate performances.

Beyond framing her biographies in the culture of their time, Valby gives vitality to the Swans though lively conversations. Although chapters are given to each woman, the book’s effect is a chorus of optimism, teamwork and faith that recognition of Black talents will grow. Their work was hard and opportunities, even in Dance Theatre of Harlem, were limited, but their accomplishments are undeniable.

Today, ballet pointe shoes come in a variety of colors, even purple.

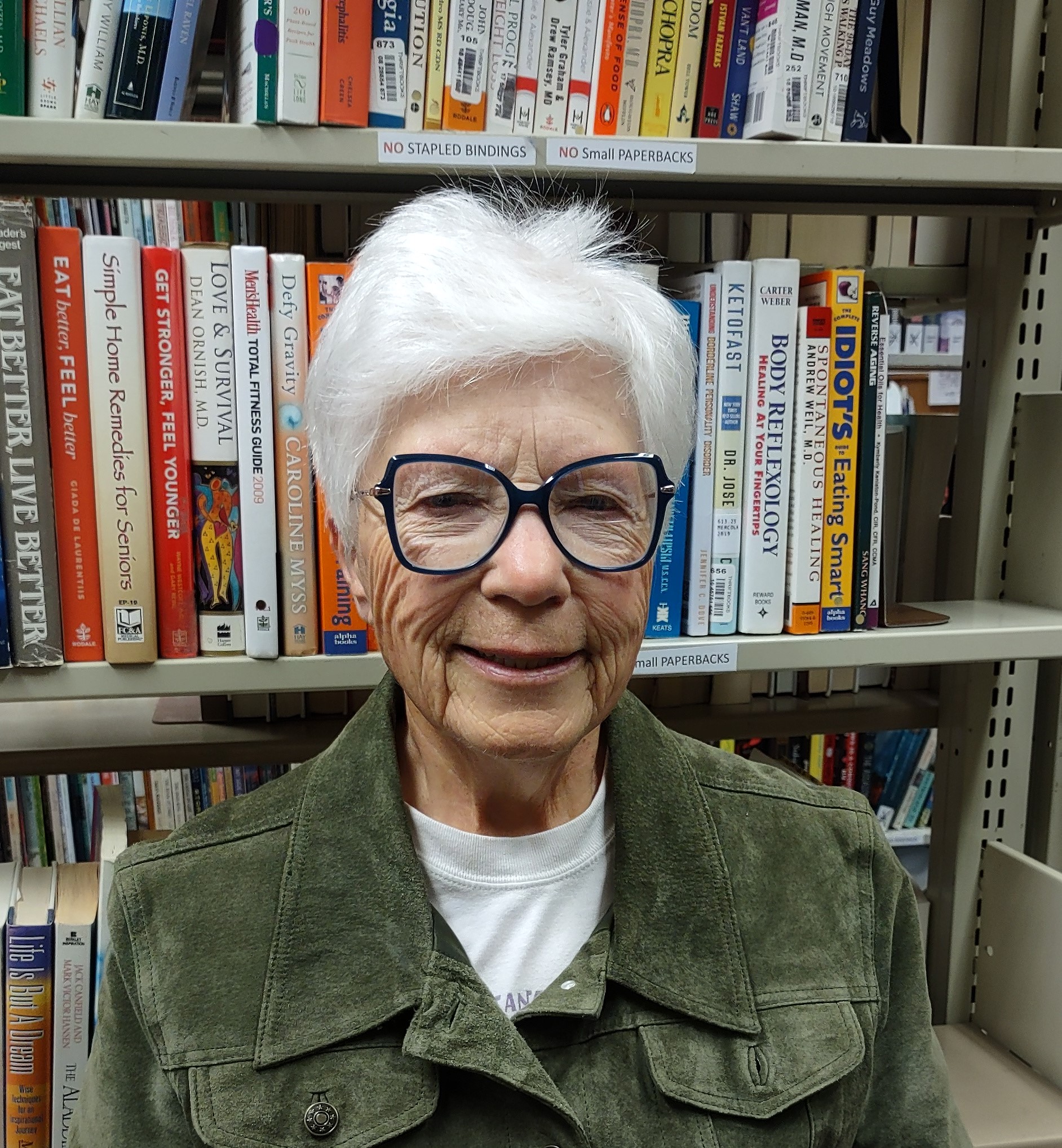

Born in Ohio but a resident of Colorado Springs since 1955, Beverly has watched the city grow. Achieving a BA from what was then Colorado State College with later graduate work at CC and University of Birmingham, England, she began a 16-year teaching career, 10 years freelancing and full-time volunteering, before spending 26 years with the Pikes Peak Library District. Author of the teachers' guide, History of the Pikes Peak Region, she is still surrounded by books and serves as a board member with the Friends of the Pikes Peak Library District.

Click here for more from Beverly Diehl.