The Storykeeper

Tim Z. Hernandez’ hybrid memoir investigates untold stories of lost loved ones and his own family

Tim Z. Hernandez’ hybrid memoir investigates untold stories of lost loved ones and his own family

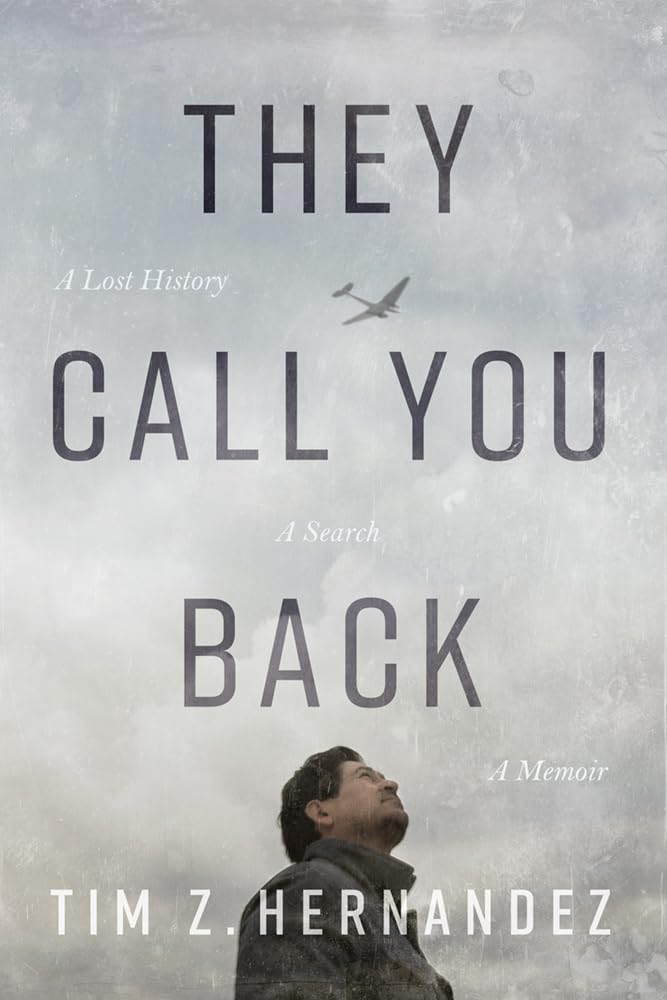

In his hybrid memoir They Call You Back, Tim Z. Hernandez—acclaimed writer and graduate of Naropa University in Boulder, Colorado—continues the story he began in his book All They Will Call You (2017). For nearly 15 years, Hernandez has been studying the history surrounding an accident that happened in 1948, a crash that would later be dubbed “the worst airplane disaster in California history.” (The crash was memorialized by songwriter Woody Guthrie in his song “Deportee: Plane Wreck at Los Gatos.”)

Tim Z. Hernandez

On January 28, 1948, a plane carrying 32 people left central California, heading for a deportation center close to the border of Mexico and the United States. While en route, a fire ignited on the plane, and it crashed in Los Gatos Canyon. All passengers were killed. There were four crew members on the flight: the pilot, the copilot, the flight attendant, and a guard. The other 28 passengers were Mexican citizens, many of whom had come to the United States legally as braceros ( U.S.government sponsored workers.) After the crash, the 28 “deportees” were buried in a mass grave in Fresno, California. News outlets did not initially release their names, and the California government did not attempt to find their families or relocate their remains to their home cities.

In All They Will Call You and They Call You Back, Hernandez details his years-long journey to find the families of those who died, and to tell the stories that have been buried beneath California soil for decades. They Call You Back, while investigative journalism in part, is also a memoir. Throughout the book, Hernandez tells his own family’s history, connecting his family members’ stories to those of the Las Gatos Canyon crash victims. Hernandez explores the ways trauma is passed from generation to generation. He describes his mother hiding with her siblings beneath a bridge during one of their father’s alcohol-fueled rages; he laments his beloved uncle who was killed by police while refusing to leave his ex-wife’s house without his son; he touches on the dissolution of his marriage and his subsequent descent into substance abuse. They Call You Back is a vulnerable, transparent account of love and loss.

All told, this book is a story about stories. It is a spiraling circle of interconnectedness and isolation. In it Hernandez questions the complexity of remembered histories—how something true may not be factual, and how something factual may not be true. He wonders how the erased stories of marginalized people affect them personally, and how that erasure impacts the way their communities, their states, and their countries misunderstand who they are. Who their predecessors were. How their kin have contributed to the tapestry of collective consciousness, and how they might continue that contribution in the years to come.

Hernandez also considers who stories are for. Who owns the memories of the past? Do they belong to families alone? Do they belong to greater communities? Who should decide when stories are told or not told? In one chapter, Harnandez describes a visit he makes to the family of one of the victims. He talks with them about their lost relative, gathering stories about who he was as a person and how his family saw him. But at the end of the interview, one of the family members says something unexpected: “We understand the importance of your work… [but] we would prefer that you don’t write about [redacted] in your book.” Hernandez is surprised by their preference. On the drive away from the family’s home, he reflects on the purpose of his project and who it is really for:

What’s a story without a name, or names, attached to it? What gets lost in the omission? What is gained? Until this moment,  it had never occurred to me that perhaps not all families want their stories told. It’s possible that for some, the media’s omission of their relative’s name afforded them protection from their own circumstances, their own history.

it had never occurred to me that perhaps not all families want their stories told. It’s possible that for some, the media’s omission of their relative’s name afforded them protection from their own circumstances, their own history.

When piecing together the stories of real people, with real families, it’s easy to get lost in the details and forget to maintain a respectful distance. Is it important to bring to light stories that hierarchical structures of power have deliberately misrepresented or destroyed? Absolutely. In telling their stories, people may be liberated; but in that telling, people may also be harmed. Investigative journalism must walk the fine line between the two.

Journalists find true-to-life stories and tell them, but they aren’t the only ones. At a different point in the book, Hernandez defines his term “the Storykeeper.” Every family, he asserts, has a Storykeeper. This person is a “believer in signs,” someone “who will travel alone to seek the answers.” It’s clear to the reader that Hernandez is the Storykeeper for his family, but he is also a Storykeeper on a larger, journalistic level—someone who will cross borders to follow leads, reach out to strangers in places he’s never been, pay attention to what people do and do not say. In They Call You Back, he records the stories he has kept for so many years. And in that recording, they become stories that belong—in ways small and large—to the history of us all.

While Marissa Harwood was born in Omaha, Nebraska, she moved to Colorado when she was four days old and considers herself a native. She grew up in the shadow of the Rocky Mountains and spent much of her childhood camping, hiking and building forts in the woods. She earned a BA in English and a Secondary Teaching License from the University of Colorado at Boulder. Later, she attended Western Colorado University and earned an MFA in genre fiction. She has taught English at three K-12 schools and two Colorado colleges. Currently, she lives in Greeley, where she teaches high school, plays with her daughter (a true CO native) and reads a lot of books. She hopes to earn a doctorate in the near future.

Click here for more from Marissa Harwood.