What the spirits, animas, hold tender

A review of Whiskey Tender, a memoir of dislocation and re-integration

A review of Whiskey Tender, a memoir of dislocation and re-integration

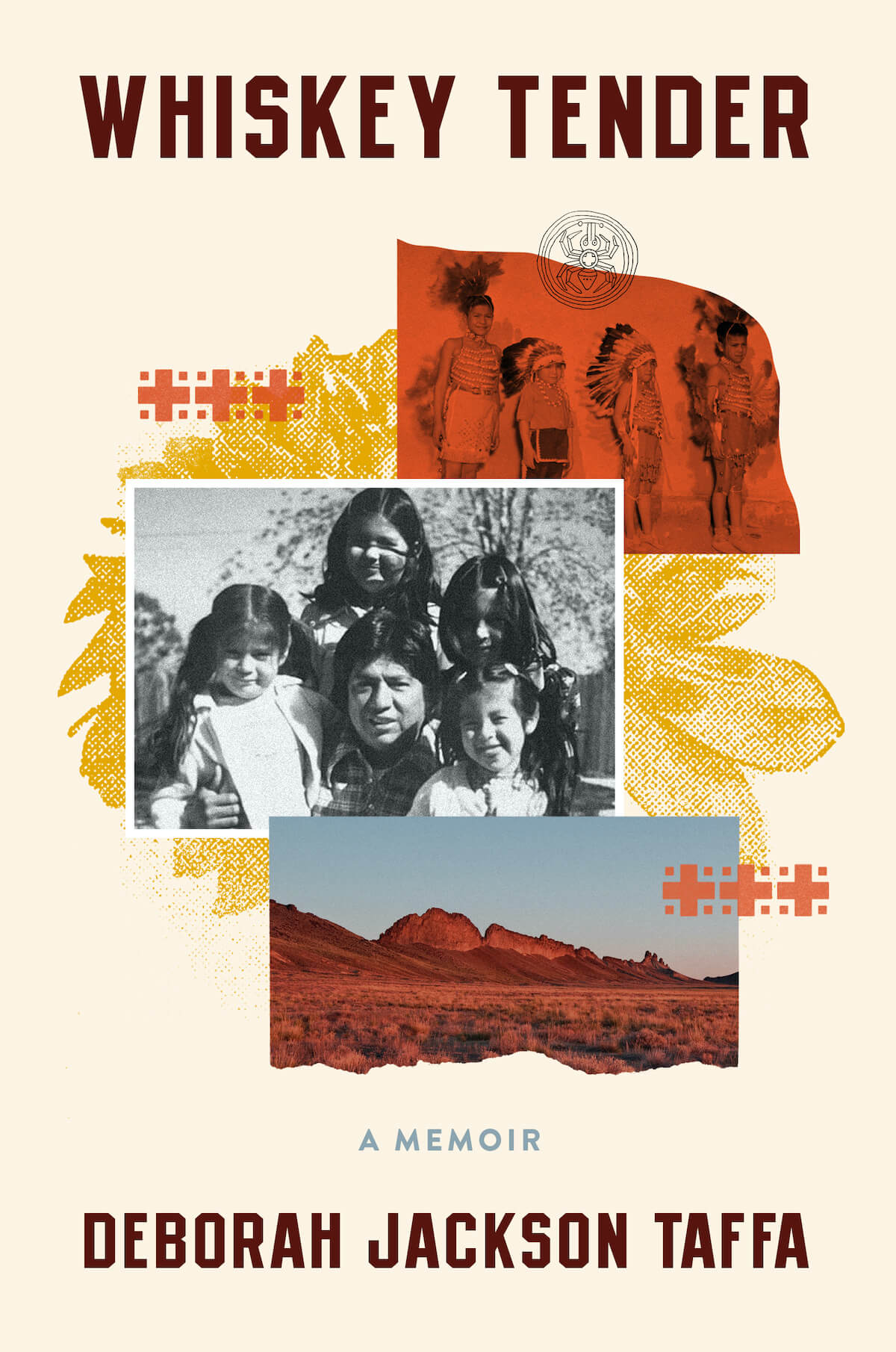

At an early age, Deborah Jackson Taffa perceived the need to document moments of living. In the acknowledgements of her memoir, Whiskey Tender, Taffa explains, “I first conceived of this book as a kid.” Whiskey Tender spans decades of the author’s life through hindsight, highlighting moments of her childhood, beginning in 1981 through her graduation from high school.

Born in 1969, Taffa, now in her 50s, is director of the Master of Fine Arts in creative writing program at the Institute of American Indian Arts in Santa Fe, NM. There she tries to instill in her students the importance of putting memory down on the page, to tell their stories, to create their own legacy to avoid erasures of the past.

As her first chapter, “Animas,” attests, the spirits remind Deborah not to “forget who I was, where I was, why I started on this journey.” Writing Whiskey Tender, Taffa shows that she is finally ready to “grow into more than a ghost child.”

Deborah Taffa

Taffa spent her childhood in Farmington, New Mexico. She is a member of the Quechan-Yuma Nation in Arizona through the paternal side of her family and is Laguna Pueblo and Chicana through her mother’s side. The 1970s in northwestern New Mexico “was a time of conflicting choices” for the family when Deborah’s parents faced the dilemma of high unemployment on their reservation or leaving home for other opportunities. They chose to raise their family elsewhere.

Her Colorado connection refers to that porous border between southern Colorado and northern New Mexico, traditionally Native land, and her family vacations camping on the Animas River near Durango.

Taffa writes because she recognizes that the stories of people of Amerindian-Chicanx heritage are often excluded from the “mythologies of American identity.” Too many corners of America are left in the shadows, their marginalities not explored though their realities are also “the iconic American story.” Taffa divulges her story, “because [she] wants Native kids to feel more connected and less lonely.”

Taffa is guided by a quest to present a contemporary likeness of herself and other Amerindian-Chicanas because, as a child, there was no confirmation of anything similar to herself or her people, no evidence that her childhood was real. She understands that her ancestors were there to support her, even if she did not draw upon their influence, and that it’s now her turn, as an elder, to link “the chain of lives that came before,” to reject the erasure of her own people and to continue their story for future generations to know.

In her second chapter, “Almost Yuman,” Taffa plays on words to describe her human condition. The Quechan-Yuma tribe are her father’s, Edmond Jackson III, and her uncles’ people. In their family, plagued by generational violence, trauma and alcohol abuse, one of their mottos is that the next generation “needed to know the truth if we were going to survive.” Her father’s parenting philosophy “was to control the pace of the world’s wounding, to dole out the pain in slightly bigger doses over time so that his kids would learn not to break under pressure.”

Their family’s pain began through disconnection with their homeland. Taffa’s father’s great-grandparents lost their land to the U.S. government through the Dawes Act in 1911. As a result of this law, if the government believed land and its resources were not being used by those currently residing upon it, the land could be seized and reallocated. That’s how many Anglo homesteaders acquired western lands occupied by Amerindian and Chicanx subsistence level and semi-nomadic agriculturalists.

Edmond’s wounds open each time the family visits some of their cherished places within Colorado. From Arizona through northwestern New Mexico to the Four Corners area of Colorado, this was his tribe’s traditional land that “stretched on as far as the eye could see.” By the 1970s, Edmond’s family was displaced elsewhere. To cope, “violence [became] a tradition on the reservation” and whiskey was its numbing medicine.

Taffa’s parents learned another survival tactic, to “twist bad things around, seeing the appearances of events in fun house mirrors, stretching memories tall and pretty” to re-member their own version of history. This is where The Relocation Act came into play, which relocated Native families off the reservation to large cities such as Phoenix, Denver, or Los Angeles to mainstream them into American society. Assimilation was not successful for all, and Taffa’s family, after relocating for government jobs, returned to the reservation when Deborah was still a young girl. By then Taffa’s mother, Lorraine López Herrera, was pregnant with another child. Still suffering from post-partum depression, she would lock herself physically into her bedroom and psychologically inside her silence.

Taffa and her siblings learned to navigate their father’s absenteeism due to work and their mother’s absenteeism from her undiagnosed clinical depression. Yet this was doubly problematic because, “[i]ndigenous belief systems hold that a child doesn’t become human until she learns who she is through her mother’s culture and lineage.” If a mother relegates herself to silence, and if she also doesn’t know the traditions of her heritage, then she cannot pass on this knowledge to the next generation. Although this was the case with her nuclear family, as an adult Taffa recovered pieces of her backstory understanding that “the more you try to suppress a culture’s belief systems, the stronger they hang on.”

In the past, many older generations suffered the severing of their relationship with land and family because of being removed from their families to whites-run and often religious-based Native American boarding schools where they were forcefully stripped of their Native identity. Both Taffa’s paternal Quechan and maternal Laguna ancestors survived this traumatic experience. In this way, by teaching at IAIA, where many of her students come from similar intergenerational traumas, her story helps articulate their own.

This understanding took a long time to develop because Taffa’s parents wanted her to succeed, but to do so away from the rez. Yet by high school, Taffa realized, “the only moments when I felt anything close to uplifted were the moments when I got the chance to explore the very culture and the history that my parents wanted me to leave behind.” Her parents had faith in the public school system, but this system purposefully excluded Native wisdom in formal education. What Taffa could not articulate then, but understands now, were the confines of institutional racism within the mask of higher education.

Here, Taffa begins her self-education by picking up Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee, the iconic history of Native Americans in  the American West published in 1970. Reading it made her ask, “Why had my parents never told me about our collective history?” When she pressed for answers in her public high school classroom, she understood that she could not represent her tribe or her family since she lacked necessary information. But she could learn to speak for herself, by gaining the courage to peel back the layers of her own learned wounds.

the American West published in 1970. Reading it made her ask, “Why had my parents never told me about our collective history?” When she pressed for answers in her public high school classroom, she understood that she could not represent her tribe or her family since she lacked necessary information. But she could learn to speak for herself, by gaining the courage to peel back the layers of her own learned wounds.

As Taffa undertakes this painful revelation, her parents begin their own disclosure. Her mother starts to share some of her own genesis, the origins of her grief and self-imposed silence. Her father confesses, “he had never realized how hard it was for me to be a half-breed … half-Native and half-Chicana … alienated, never able to fit in either world.”

In “Flight (1987)” the Jackson family confronts the silence and shame they had previously agreed upon. In this way, Taffa’s personal resentment is named and spoken. She vows “to make my life better for the little girl I’d once been.” This comes through two pivotal events: a failed suicide attempt by downing a bottle of Tylenol and the tragic car accident that cuts her sister’s life short.

Rather than continue on a conventional route, Taffa chooses her own path. After crossing the stage for her high school diploma, she embraces her personal wanderlust instead of college. This leads her to stints in Yellowstone National Park, Maine, Alaska, Indonesia and West Africa. Her “flight” is a different kind of escape, one where she is “running toward rather than away.” Her beautiful dream is “not tethered to ceremony or song;” instead it is a “nomadic and found awe” in the earth.

Whiskey Tender documents Taffa’s life through hindsight. She couldn’t have articulated any of this as an 18-year-old. She writes:

“[A] person teaches best what she needs to learn, and reconnecting with my homeland, rediscovering my center as it relates to my past, claiming my inheritances as a woman whose spirituality is deeply rooted in the desert, is what I most needed when I started writing this book.”

Even when absent, like her father was from the Yuma reservation, or like she was through her days of exploration, Taffa believes in the land and remembers its peoples’ names. She gleans this concept from author Barry Lopez:

“If you’re intimate with a place, a place with whose history you’re familiar, and you establish an ethical conversation with it, the implication that follows is this: the place knows you’re there. It feels you. You will not be forgotten, cut off, abandoned.”

Taffa trusts her instincts, concluding:

“We are at home on this planet when we feel the sacred places rising up through our feet, when we embrace the mountains and desert arroyos. … The Ancient Ones walk beside us, and all we must do is keep our fingers on the pulse. … If we listen, we can hear it rising up … The sound of the spirit that was, is and always will be.”

Whiskey Tender is Taffa’s testimony to herself. In it she reminds her students and her readers that if we listen well, the land has things to tell. The animas, the spirits, will keep our names sacred and embrace us within our chosen paths.

Shelli Rottschafer (she/her/ella) completed her doctorate from the University of New Mexico in 2005 in Latin American Contemporary Literature. From 2006 until 2023 Rottschafer taught at a small liberal arts college in Michigan. Summer 2023 she began her low-residency MFA in Creative Writing with an emphasis in Poetry at Western Colorado University, Gunnison. Together with her partner and rescue pup, she resides in Louisville, Colorado and El Prado, Nuevo México.

Click here for more from Shelli Rottschafer.