An immigrant family’s odyssey and triumph

From Vietnam to Arkansas to Colorado, with courage and grace

From Vietnam to Arkansas to Colorado, with courage and grace

In 1975, the Vietnamese War ended with the collapse of the South Vietnamese government. The country was in turmoil as the new communist leaders took charge. No one knew what was going to happen, but everyone knew people of Chinese descent were most at risk.

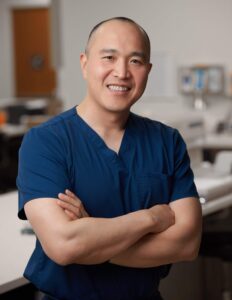

Vinh Chung

Vinh Chung’s family was among those people. Their business and property were seized, and they faced a future of upheaval and poverty.They decided to leave Vietnam.

The Chung family joined a movement that would come to be called the Vietnamese Boat People—an estimated two million people fleeing Vietnam by boat. Over two decades, 800,000 Vietnamese reached other countries safely; between 200,000 and 400,000 died on their journeys.

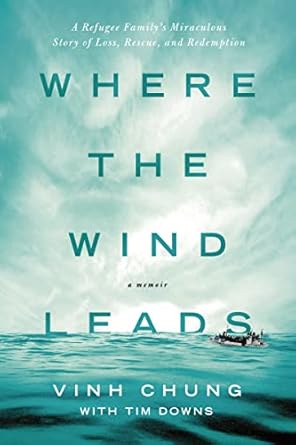

Chung, a dermatologist who lives in Colorado Springs, was just three and a half when his family fled. His memoir, Where the Wind Leads, is a riveting account of that harrowing journey for the Chungs and their eight children to a new life in a new place.

Where the Wind Leads weaves together three distinct stories: the story of a traditional ethnic Chinese family who became wealthy with a lucrative business started by their grandmother; the story of their decision to leave their homeland on what would become a nearly impossible journey; and the story of the new, unfamiliar life they stepped into, in the heart of the United States in Fort Smith, Arkansas.

Chung was born just eight months after the country fell to communists, in April 1975. When he was three and a half, his family fled their country. The Chung family business, a multi-million-dollar rice milling company, was gone.

On June 12, 1979, a hot, sticky day, the Chungs set off with nearly 300 others on a 70-foot-long boat. The stress of leaving and the 90-degree heat made loading difficult, Chung writes. Many of those fleeing, knowing they would never return, tried to bring precious possessions, “steamer trunks, bedding, pots and pans, rice cookers – even furniture.” Others had gold and jewelry hidden or sewn in the seams of their clothing, in hopes of paying for a new life at their unknown destination. “It was hard to blame them since they were leaving Vietnam for good and knew that anything they left behind would become the government’s property,” Chung writes.

Finally, the overloaded ship pulled away from the dock. Those onboard weren’t sure where they were going, and they had no idea how their journey would unfold.

What followed were weeks of misery and danger. There was little food; they sometimes went for days without water. There was fear of drowning or illness or attacks by marauding pirates that patrolled the South China Sea. When they did reach land, they were forced to live in makeshift refugee camps with no shelter, where they roasted in the relentless sun. Finally, the refugees were promised transport to an official refugee camp off the coast of Malaysia. They were separated into four groups, each group herded aboard a rickety fishing boat and towed out to sea for 24 hours. There, the boats were set adrift with no oars, no power, no sails, and no way to navigate.

Chung’s family’s boat, overflowing with 90 people, soon lost sight of the other three, and it drifted for days before they were miraculously spotted by Operation Seasweep, a ship sent out by World Vision, a Christian relief organization, to help stranded refugees.

The ship that saved them finally docked in Singapore and, on Oct. 25, 1979, more than 100 days after they began their  journey, the Chungs boarded an airplane bound for America.

journey, the Chungs boarded an airplane bound for America.

Their destination was a small American city they had never heard of, in a state they had never heard of. Sponsored by a church, they were given temporary housing and a small amount of money for food, housewares and toiletries. No one in the family spoke English, and Chung writes, “adjusting to life in America was no harder than it would have been on any other distant planet. That was what America was like to us: a different planet.”

As the Chung children navigated school, their parents set out to create a new life for them. Chung’s father, who had been a wealthy COO in Vietnam, could only find work in factories, and eventually got a job at a company that manufactured air conditioning units, staying there for 23 years.

Chung’s parents—especially his father—expected their children to work hard and succeed at their new life. They all did, with Vinh receiving a scholarship to Harvard. He graduated from Harvard with a B.A., was a Fulbright scholar researching herbal medicine at the University of Sydney, holds a Master of Theology degree from the University of Edinburgh and graduated from Harvard Medical School in 2004. He has served on the board of World Vision, the organization that rescued his family.

First published a decade ago, Chung’s book is just as relevant now. People from around the world are fleeing economic, social and political instability. In this country, we see thousands trying to enter the U.S. at the southern border with Mexico. Those immigrants aren’t arriving by boat, but many have traveled on foot for more than 1,500 miles, maneuvering through dense rain forests, steep mountainsides, rivers and swamps. They arrive with different stories than the boat people, but their perseverance and desire for a more stable life is just as compelling as this true story of a fellow Coloradan.

Deb Acord is a journalist and author from Woodland Park, Colorado. For decades, she wrote for The Colorado Springs Gazette, Rocky Mountain News, Denver Post and The Indy. At the Gazette, she was co-creator of Out There, a section devoted to the outdoors of Colorado. She is the author of Colorado Winter and Biking Colorado’s Front Range Superguide and has writtten car trend stories and environmental stories for Popular Mechanics.

Click here for more from Deb Acord.