Taking the extra step

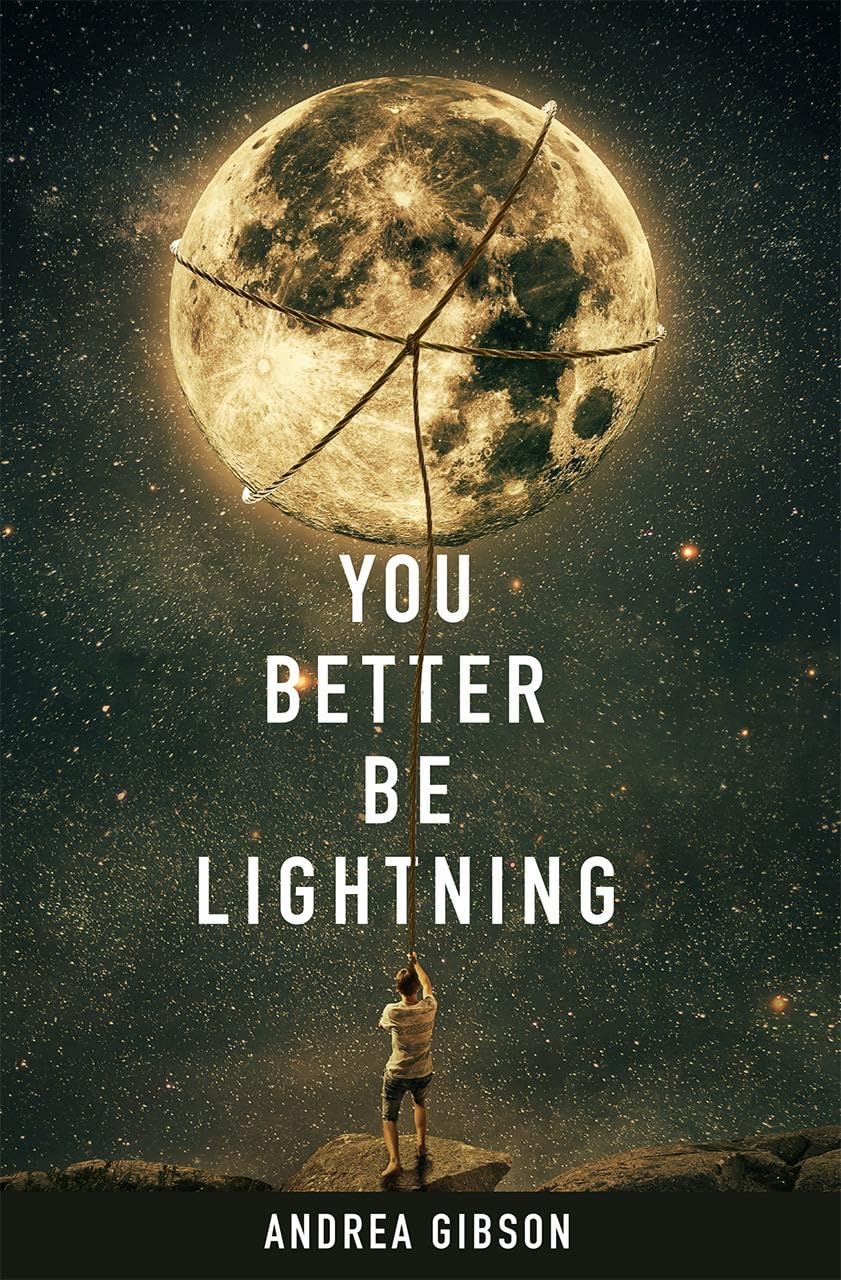

Colorado Poet Laureate Andrea Gibson’s collection calls readers to understand and to love

Colorado Poet Laureate Andrea Gibson’s collection calls readers to understand and to love

Andrea Gibson

Sometimes poems are abstractions, attempts to pin down and name something unnamable. Sometimes they are breathing images full of color and texture and movement. Sometimes they are stories. And sometimes, in the hands of a deft and deeply thoughtful writer, poems are all of these things. You Better Be Lightning, Colorado Poet Laureate Andrea Gibson’s 2021 collection, is full of poems that are abstractions and images and stories combined. Reading it is like watching the morning street from the patio of a coffee shop. And it’s like calling your best friend in the middle of the night because your heartache is too much for you alone.

Gibson, Colorado’s tenth poet laureate and nationally beloved spoken word performer, writes about connections, relationships that have come and gone and come again. Actions that will reverberate through future generations. Scattered memories of, as Gibson says, “the ashes of my friends who were still alive last year.”

Many of the poems in this book are long, and they explore these connections through detailed storytelling. However, there are also tiny poems scattered throughout this book, poignant blips that contain within them stories just waiting for us to imagine. One poem, “No Such Thing as an Innocent Bystander,” reads: “Silence rides shotgun / wherever hate goes.” Here, Gibson evokes an image of sitting in the passenger seat of a car, along for the ride, seemingly without any control over the destination. Is it possible for the passenger to navigate the driver down a different road?

Another poem, titled “Spelling Bee Without Stinger,” is composed of three lines: “I love myself / is often spelled / g-o-o-d-b-y-e.” Gibson writes frequently in this book about the idea of letting go as a method of healing, and this small poem cuts to the heart of that sentiment in one clean stroke. Yet another small poem (my personal favorite), “Life Sentence,” is only one line: “I finally have a wrist that is sharper than the blade.” It is a poem that works on multiple levels—conceptually, it is about overcoming thoughts of suicide and understanding that you are stronger because of your experiences. This is the “life sentence”—the speaker is condemned to live with these experiences and their strength until they die. Additionally, when we consider the composition, we cannot overlook the fact that the entire poem is one sentence about life.

Through all of their poems, short and long, Gibson examines complex  issues like homophobia, gender identity, climate change, suicidal ideation and sexual assault. These issues are picked apart and transformed into relatable, lived-in moments that all readers can feel.

issues like homophobia, gender identity, climate change, suicidal ideation and sexual assault. These issues are picked apart and transformed into relatable, lived-in moments that all readers can feel.

Take their poem “Queer Youth are Five Times More Likely to Die by Suicide.” The title is a statistic. Throughout the stanzas that follow, Gibson translates that number by personalizing it, by allowing the reader glimpses into the live of those young people: “means: / Burning for eternity seemed five times / more doable than another day in the school lunchroom. / means: / You were five times more inclined / to triple-padlock your diary. / means: / You were five times more likely / to stop writing your story down.” In these lines, the reader is transported to a childhood of unhappiness and desperation, a childhood they may or may not relate to. And later, when the speaker walks through “graveyards with a chisel / correcting the names of trans kids / whose families said, No, when asked, / Can you just let me live?” we feel the tragedy like a physical blow. It is impossible not to imagine the countless children who believed suicide was their only feasible option, the only possible outcome after an adolescence filled with derision and fear.

But here’s the thing: Gibson doesn’t stop there. They never stop in those moments of misery. Instead, they take us a little further, into a future where there is more beauty and hope:

Five times more likely to:

adore the last man who walked on the moon

just because he wrote his daughter’s initials there.

To know there is no universe in which they would not

be proud of their own children.

Queer youth are five times more likely to:

see you how you dream of seeing yourself.

To write something in your yearbook that will get you

through the next decade. To spot a stranger crying

and ask if there’s anything they can do to help.

Five times more likely to:

need us to do the same.

In many of Gibson’s poems there is a call to action, stated directly or flowing beneath the lines like an undercurrent. And the actions they call us to are simple: love other people, love your planet, love yourself and all your flaws. The actions are simple. But that doesn’t make them easy.

While Marissa Harwood was born in Omaha, Nebraska, she moved to Colorado when she was four days old and considers herself a native. She grew up in the shadow of the Rocky Mountains and spent much of her childhood camping, hiking and building forts in the woods. She earned a BA in English and a Secondary Teaching License from the University of Colorado at Boulder. Later, she attended Western Colorado University and earned an MFA in genre fiction. She has taught English at three K-12 schools and two Colorado colleges. Currently, she lives in Greeley, where she teaches high school, plays with her daughter (a true CO native) and reads a lot of books. She hopes to earn a doctorate in the near future.

Click here for more from Marissa Harwood.