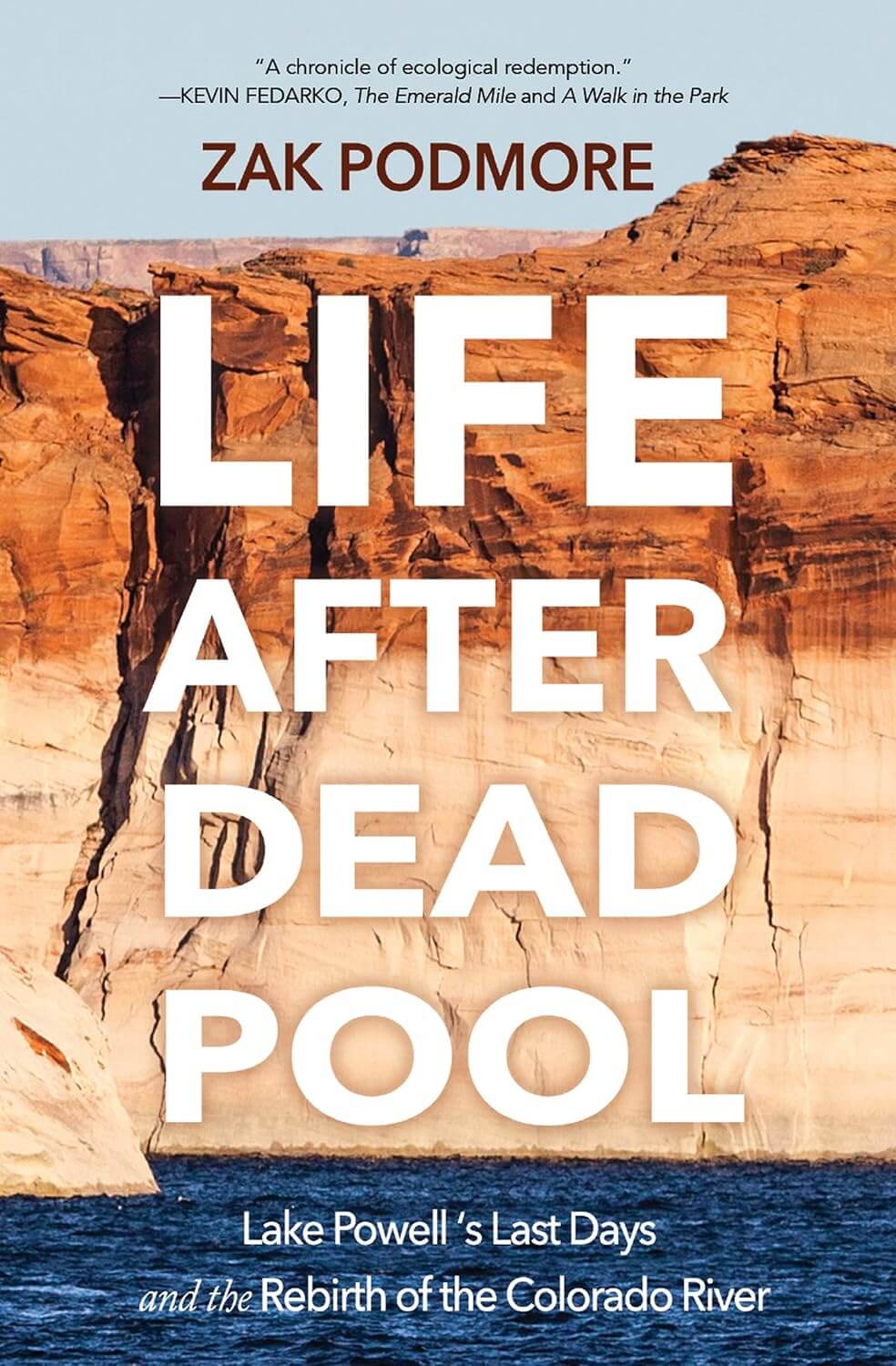

A river-level view of change

Life After Dead Pool investigates Lake Powell’s diminishing waters and the future of the Colorado River

Life After Dead Pool investigates Lake Powell’s diminishing waters and the future of the Colorado River

At “full pool,” Lake Powell offers 1,960 miles of shoreline. By comparison, California’s coastline runs 840 miles.

At “full pool,” you could drop the Statue of Liberty into the water behind Glen Canyon Dam and her torch would be more than 200 feet below the surface.

Zak Padmore

And if you’ve ever spent a week on a houseboat cruising the main channel or more than 90 side canyons up and down the massive lake, you know the appeal. Towering red rock cliffs. Endless fishing and frolicking options. Magical starlit nights.

But there’s a problem. The lake, created by construction of the Glen Canyon Dam in northern Arizona with the vast majority of the pool in southwestern Utah, has been drying up for the past 25 years. The lake reached “full pool” in 1980 but that didn’t last long. The decline began in 1983 and lake levels have been struggling ever since. Today, water levels hover around 32 percent of capacity. The idea of Lake Powell, as hydroelectric powerhouse for the southwest, doesn’t work if the water doesn’t flow from the Rocky Mountains in Colorado.

And here’s something I learned reading Zak Podmore’s excellent Life After Dead Pool: Lake Powell’s Last Days and the Rebirth of the Colorado River: there’s no drain at the bottom of the dam. Once the water drops below the eight large penstocks and then below the river bypass tubes, at an elevation of 3,360 feet above sea level, Lake Powell will have nowhere to go. It’s a scary proposition.

“At dead pool,” writes Podmore, “the Grand Canyon—which begins just downstream from the Glen Canyon Dam—would see some of its lowest levels in decades, threatening endangered species recovery programs and its world-famous river recreation. Lake Mead, which lies at the other end of the Glen Canyon from Lake Powell, would soon reach dead pool levels as well, and the 27 million people who rely on Colorado River water in Nevada, Arizona, California and northwest Mexico could see their supplies dry up. Yet Lake Powell would still reach 100 miles upstream at dead pool. Billions of gallons of water would essentially be trapped in the reservoir.”

This is a scenario, as Podmore notes, to be avoided at all costs. But what do you do when the snowpack is low and the rains don’t come to the Colorado mountains that feed the river from hundreds of miles away?

Buy from you local independent bookseller or at bookshop.org.

Life After Dead Pool, through the eyes of a journalist who has been writing about water and the environment in the western United States for more than a decade, is a thoughtful meditation on the woes ahead. It’s also a river-level view of the changes. Podmore is an experienced (that’s putting it mildly) kayaker. He’s a water bug with a writer’s keen eye for detail. He previously wrote a series of essays in a volume called Confluence: Navigating the Personal and Political on Rivers in the New West. He revisits some of those moments here, including his source-to-sea journey down the Colorado River to where the flow goes to die in the Sea of Cortez. Podmore is the kind of guy who hikes 100 miles from Lake Powell to his home in Bluff, Utah to better understand the terrain.

Life After Dead Pool is a blend of water-level detail, big policy and practical questions, including what to do with the sediment building up in the basin.

“Even if lake Powell’s water level were to stabilize for a long period, neither rising nor falling by an inch, the delta—the mountain of mud that the river flows on top of—would keep it advancing… (like) a glacier grinding down a mountain valley,” writes Podmore. “Like a true glacier, the mud slug is an active geologic force that rearranges the landscape it passes through, filling low points and allowing the river to take courses it would not have followed had it been contained by long established channels and low canyon walls.”

Yes, problems abound. But Podmore notes bright spots, including the return of native plant species as the water levels have dropped. That resurgence in many side canyons, he argues, is a positive sign that the rest of the canyon will return to supporting diverse ecosystems if given time to heal.

Podmore introduces us to a bevy of scientists and advocates trying to navigate the best way forward. Smartly, he introduces us to Native Americans with their perspectives and artists, too. Podmore takes us to conferences with water bureaucrats where the level of alarm and concern feels feeble in contrast with the decades-long trends. And he draws an extended, effective metaphor with gambling in Las Vegas and makes a compelling case that those in charge of water management and water policy simply have no idea how to realize that the house always wins. Life After Dead Pool is not a polemic. The writing carries the thoughtful, matter-of-fact tone of writers such as Craig Childs or David Gessner.

One thing is clear after reading Life After Dead Pool—managing the process of taking the dam offline will carry as much weight as when that first bucket of cement was poured into the narrow spot in the canyon back in the summer of 1960.

“It is the river that ultimately wins,” writes Podmore. “There is no engineer skilled enough nor any dam strong enough to defeat the simple recipe of gravity and water and sedimentation.”

Mark Stevens is the author of No Lie Lasts Forever (June 2025 from Thomas & Mercer), The Fireballer (Lake Union, 2023), and The Allison Coil Mystery Series including Antler Dust, Buried by the Roan, Trapline, Lake of Fire, and The Melancholy Howl. He lives in Mancos. Read more at www.writermarkstevens.com.

Click here for more from Mark Stevens.