Imagining the unthinkable

Annie Dawid’s novel of Jonestown reimagines the phenomenon of Jim Jones, his followers and their undoing

Annie Dawid’s novel of Jonestown reimagines the phenomenon of Jim Jones, his followers and their undoing

“For some unexplained set of reasons, I happen to be selected to be God.” So said Jim Jones, the charismatic cult leader who led his followers from the Peoples Temple in San Francisco to sweltering Guyana, in July of 1977. There, on a “revolutionary agricultural mission,” they struggled to establish a socialist utopia. Love and peace in the New Jerusalem Jungle? Not exactly.

In Guyana, they were hot and hungry, and Jones—whom many had once called “father”—was becoming increasingly unhinged and delusional. Fearing a nuclear holocaust in the U.S. was imminent, he believed members of “Jonestown” could build a self-sufficient society based on freedom, equality and justice. But it was brutal work, and there wasn’t much food. Complainers were targeted. Informers lurked around every corner. During nighttime propaganda meetings, rule-breakers were humiliated and beaten with a wooden paddle.

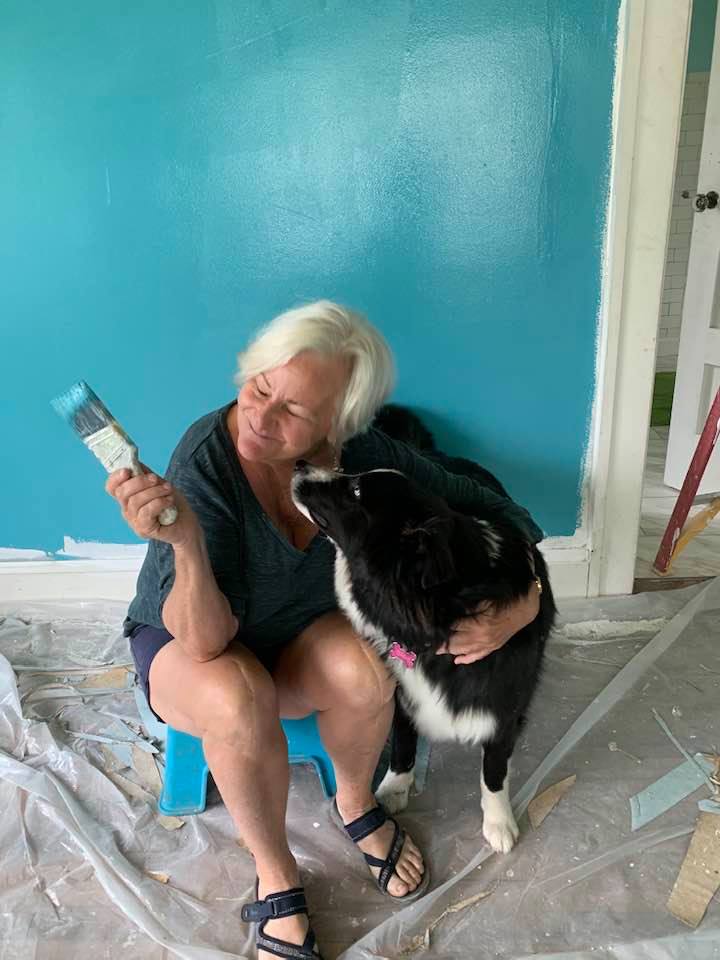

Annie Dawid

When authorities back in the U.S. learned that some people were being held against their will, U.S. Congressman Leo Ryan and an entourage flew out to investigate. After meeting with Jones and others on Nov. 17, 1978, Ryan and his group tried to leave Guyana the next day. A few, including Ryan, were shot and killed on the airstrip by Temple members.

What happened next is burned into the American psyche. Jones announced that members must commit “revolutionary suicide.” Under his direction, aides mixed up batches of fruit punch laced with cyanide and sedatives. Those who resisted drinking the potion were forcibly injected. On November 18, in the span of a few hours, 918 people died. (Jones died of a gunshot to the head; it’s unclear whether he was shot or committed suicide.)

How could such a thing have happened? Who was Jim Jones and how was it possible that a single man could orchestrate the country’s biggest single loss of civilian life in the 20th century? These are some of the questions raised in Annie Dawid’s novel Paradise Undone: A Novel of Jonestown. Based on years of research, interviews and listening to Jones’s taped end-time sermons, Dawid, who lives in Silver Cliff, Colorado, nimbly constructs a partly imagined version of Jonestown. Told through differing perspectives, it’s a story of hope, disillusionment and, later, terrible violence and cold-blooded manipulation.

Through the composite character of Watts Freeman, a Black former drug addict and Temple member who survived the massacre, we learn of Jones’s charisma and weaknesses. (He was a “star hypochondriac,” Watts tells an interviewer. What’s more, the leader’s infidelities were well-known at the compound.)

Virgil Nascimento, a former U.S. ambassador of Guyana who married a Temple member, wrestles with deep feelings of revulsion and disgust after the killings. He is haunted over Jones’s identity. “What to call Jones?” Nascimento writes. “The Reverend—though revered for what, I couldn’t say…Psycho. Devil. Charlatan. Megalomanic. Monster. Madman.”

Paradise Undone is painful to read. I was living in the San Francisco Bay Area in 1978 when the news about the shocking massacre rocked the world. Dawid’s probing questions about personal responsibility, groupthink and mind control hit close to home because I’d lived in a Christian commune in the ‘70s. Though the Lighthouse Ranch was not a “cult,” I detect some uncomfortable similarities between it and members of the People’s Temple. Like them, I too once believed in a spiritual and moral cause, threw my lot in with others, sacrificed for a larger purpose and learned to distrust outsiders.

How easy is it to get caught up in a high-minded movement? In the 1970s, it was quite easy. It was an idealistic time, and the “Jesus Movement” was sweeping the country. At the Lighthouse Ranch, personal freedoms were quashed in the name of discipleship. We pooled our resources, worked a variety of jobs and were focused on a higher mission: bringing souls to Jesus. Some people called us “Jesus Freaks,” but the labels are limiting. Like members of the Peoples Temple, some of us were at odds with the world, adrift, floating. Former drug addicts, veterans suffering from PTSD, idyllic college grads, romantic back-to-the-land hippies, we ended up at the ranch, all wanting heaven, right here on earth.

Truth Miller, a fictionalized character who helped run the organization back in San Francisco, represents those who remained true to Jones’s vision even after the tragedy. She calls those who defected “traitors” or “That Woman.”

Jones’s wife, the long-suffering Marceline, has the most insightful point of view. She is the one closest to Jones; who knows his history, who sees his gradual evolution from devoted street preacher and civil rights advocate to power-hungry cult leader.

Through her, we get a glimmer of Jones’s enormous charisma and idealism. Jones grew up dirt-poor in Indiana. From an early age he showed an affinity for religion, particularly Pentecostalism. In 1949 he’s working as a hospital orderly in Richmond, Indiana, when he meets nurse Marceline Mae Baldwin. A Methodist minister’s daughter, she is impressed by Jones’s compassion. They marry, eventually adopt a “rainbow family” of children, and become a galvanizing example in segregated Indiana. Their church, Wings of Deliverance, eventually morphs into Peoples Temple Full Gospel Church. Membership multiplies, the mission expands; members move to Humboldt County, California, then San Francisco, and finally, in the late-70s, to Guyana.

early age he showed an affinity for religion, particularly Pentecostalism. In 1949 he’s working as a hospital orderly in Richmond, Indiana, when he meets nurse Marceline Mae Baldwin. A Methodist minister’s daughter, she is impressed by Jones’s compassion. They marry, eventually adopt a “rainbow family” of children, and become a galvanizing example in segregated Indiana. Their church, Wings of Deliverance, eventually morphs into Peoples Temple Full Gospel Church. Membership multiplies, the mission expands; members move to Humboldt County, California, then San Francisco, and finally, in the late-70s, to Guyana.

Although outsiders depicted Temple members as brainwashed, unintelligent, and easily manipulated, Paradise Undone shows that Jones’s followers were just people, representative of their time, hoping to effect change in an era of dramatic cultural upheaval.

In tumultuous Jonestown, Marceline seems like the sane one. She serves as Jones’s steadying influence, the logical accountant who interacts with the outside world, a nurturing mother figure who tries to keep the faith. But even nice people can be complicit.

After years of her husband’s infidelity and hypocrisy, Marceline is wise to him. “Only now could she see the core of this clay-footed idol, not a great man but just a man,” Dawid writes. “Like any other. It seemed to Marceline that the greater the vision, the more numerous the foibles, the petty horrors.”

Still, she doesn’t act at the decisive moment. Begging him to reconsider the mass suicide plan, Dawid writes, “She had never stood up to Jim, and now when she really needed to, she was still unable to do it. She despised herself.”

Defectors lucky enough to escape Jones’s clutches could get on with their lives and re-evaluate history at a distance. Those who were either forced to commit suicide or were murdered by Jones’s enforcers didn’t have that luxury. But giving up, acquiescing, in the face of overpowering strength, is never acceptable.

The only person who defies Jones’s murderous plans is Christine Miller. From FBI tapes gathered after the tragedy, Miller is heard pleading with Jones that killing children is wrong. When Jones ignores her, she persists. “But I still think, as an individual, I have a right to say what I think. What I feel. And I think we all have a right to our own destiny as individuals.”

D’Arcy Fallon, an award-winning former Colorado Springs Gazette reporter, lives in Springfield, Ohio. A professor emerita of Wittenberg University, she is the author of a memoir, So Late, So Soon (Hawthorne Books), about living in a religious commune in the ‘70s. Her work appears at https://darcyfallon.substack.com.

Click here for more from D'Arcy Fallon.