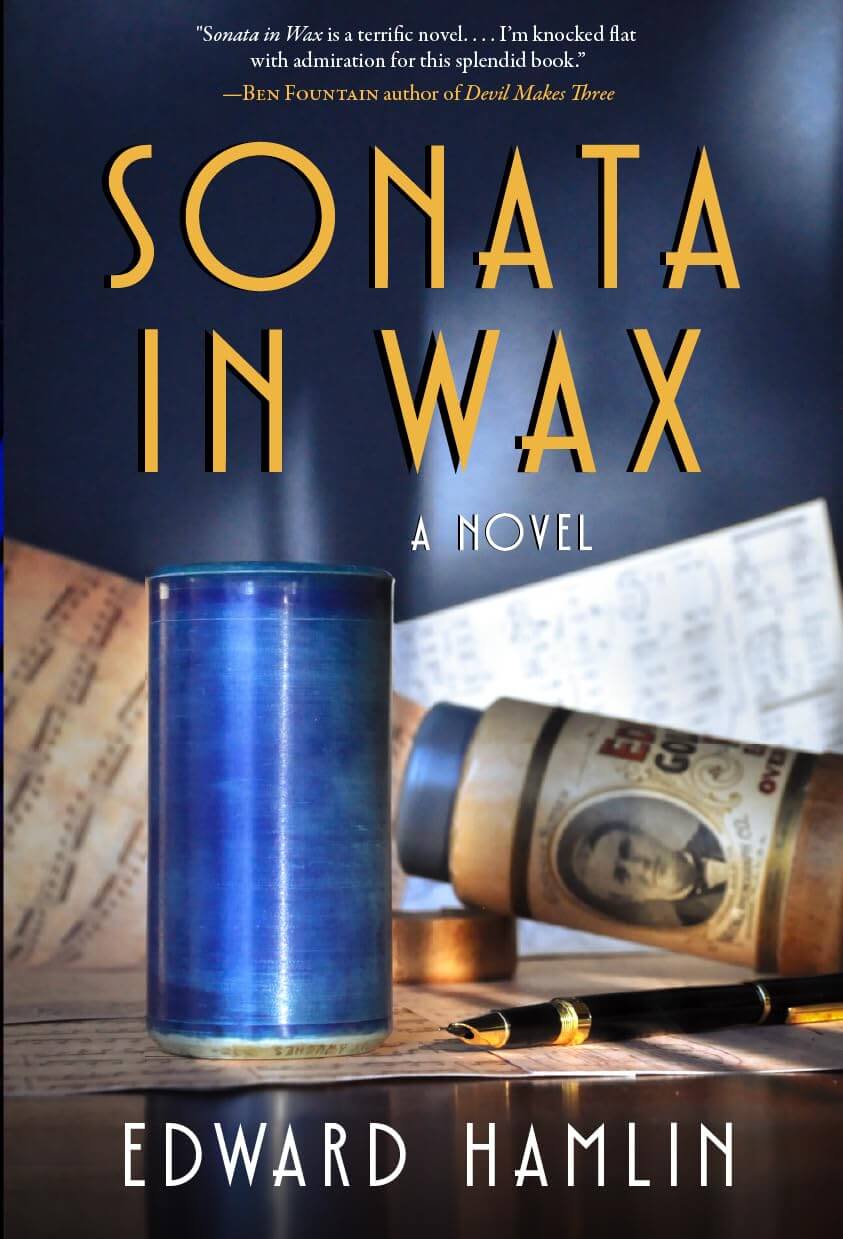

‘Dazzling and feverish and wild’

Music for the parched heart in Edward Hamlin’s debut novel

Music for the parched heart in Edward Hamlin’s debut novel

I am not a musician. I tinkered on the piano a little as a young person and became a decent sight-reader. Only three times in my long life as a reader has a novel opened for me the mysteries of music—how it feels to play an instrument, what comprises a composition, how music transports the person making it and the person receiving it.

Edward Hamlin

The first novel that taught me something deeply felt about music was Frank Conroy’s 1996 novel, Body and Soul, about a child prodigy, pecking away at an out-of-tune piano in a New York tenement basement, who becomes a concert pianist. The second was Richard Powers’ 2003 novel, The Time of Our Singing, about a family deeply defined by classical music. The parents, a biracial couple, meet at a 1939 Marian Anderson concert on the Mall in Washington, DC. One critic called it “heady, panoramic … for full orchestra.”

The third was just recently, reading Colorado author Edward Hamlin’s sumptuous novel, Sonata in Wax, published last year. Hamlin is a highly accomplished writer of short stories, winner of numerous prizes and a heralded composer and guitarist as well. Sonata in Wax is his debut novel, a book certain to find a devoted following among readers like me, those who want to vicariously participate in the making of music.

(It’s worth noting that all three of these novels involve integrating classical music with jazz, making them distinctly American.)

Sonata in Wax begins with a Prelude, a breathless description of the novel’s lead character Ben Weil, a classical music producer, hearing the sonata of the title for the first time. “It’s the direct transmission of a vision,” Hamlin writes. “As the recording comes to a close Ben sees the lost sonata for what it is: a dream of modernity, dazzling and feverish and wild as only the truest dreams are.”

The lost sonata in question arrives in Ben’s mail in the form of five wax cylinders, recordings made early in the last century to be played on the graphophone, an invention of Alexander Graham Bell. An accompanying letter explains that these are home recordings made at a family gathering at Aigremont, a mansion in Winchester, Massachusetts, outside of Boston on Oct. 1, 1917. “American debut of Fr. Piano sonata. Performed by J. Garner [a misspelling of the French name Garnier] for an invited audience,” the label reads. That’s all Ben knows  about this visionary music’s provenance, but his life is soon transformed by his search for its composer, the virtuoso pianist on the recording.

about this visionary music’s provenance, but his life is soon transformed by his search for its composer, the virtuoso pianist on the recording.

Hamlin organizes the novel as a braided timeline—present day Chicago, 2018, alternates with Massachusetts a century earlier, at the end of the Great War and the beginning of the influenza epidemic. Progressing events in both centuries are set as the musical movements of a classical sonata: Andante, Allegro, Minuet or dance, and Finale. The movements are repeated enough times throughout the novel that we begin to hear them in our minds. What is unraveled through this repetition and Ben’s relentless inquiry into the music’s origin is not only the sonata’s origin story but Ben’s as well. We travel through his career as a pianist who no longer performs but records others; through divorce from his musical soulmate; to a health crisis that could well end his career as a professional music listener; to an ill-advised but unavoidable clash with a high-strung musician/lover; to resolution of his own past and present alongside the story of the sonata’s creator and his descendants.

Sometimes you want a single movement, a slip of a novel that won’t weigh you down for long. And sometimes you want to stay and indulge in the novelist’s richly imagined world. Sonata in Wax offers the latter experience, driving the reader toward an inevitable end she dreads reaching.

The 1917-18 scenes are as rich as those set in Ben’s present. Driven by Elizabeth, a French immigrant who supports herself and her father by calling on well-heeled New Englanders and selling Bell’s graphophones, these scenes gradually reveal to us the secrets of the sonata: why there is a strange but deliberately placed seven-beat pause at the end of the first movement; which French composers were contemporaries of Garnier and which influenced the sonata he wrote after leaving France for America; the sources of Garnier’s deep grief and expansive joy, both expressed in the sonata.

I took issue momentarily with what I believed to be a one-too-many plot twist near the end of the book, but I quickly changed my mind. Hamlin pays for and earns the ending to this exquisite novel, full of drama and humanity and tragedy and rescue and truth and lies and heritage and … music, glorious music.

Click here for more from Kathryn Eastburn.