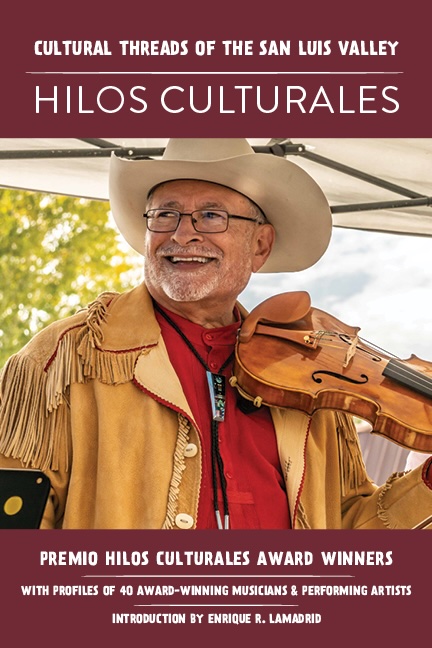

Creativity, culture and tradition in Colorado’s San Luis Valley

Book honors stewards of Hispano traditions in one of the state’s true cultural enclaves

Book honors stewards of Hispano traditions in one of the state’s true cultural enclaves

“I didn’t cross the border, the border crossed me.” — a lament characterizing San Luis Valley settlers’ predicament for centuries

Colorado’s San Luis Valley has been subject to shifting, often contentious, borders ever since early Spanish explorations. At first, physical barriers defined the cultural contours of the Valley. Then came the creation of geopolitical boundaries where Spain, Mexico and, subsequently, the United States, imposed various borders answerable to imperialism, colonization, and commerce, e.g., the Santa Fe Trail in 1821.

In 2017 History Colorado embarked upon the Borderlands of Southern Colorado project with the goal of carefully examining various outcomes of these shifts through time and space. Hilos Culturales: Cultural Threads of the San Luis Valley, is part of that exploratory continuum.

Published in 2023, it’s a slim book with substantial heft and breadth. Contents include the foreword by Sam Bock celebrating the cultural importance of language and the power of expressive culture to cross borders and chart social change. The first essay by Charles Nicholas Saenz details the cultural landscape of the valley and the history of settlement inscribed upon it. Enrique Lamadrid’s rich and extensive introductory essay constitutes a major part of this book providing a context for the 40 award winners featured in the final section. Hilos Culturales was a finalist in the Colorado Book Awards largely due to Lamadrid’s essay.

Published in 2023, it’s a slim book with substantial heft and breadth. Contents include the foreword by Sam Bock celebrating the cultural importance of language and the power of expressive culture to cross borders and chart social change. The first essay by Charles Nicholas Saenz details the cultural landscape of the valley and the history of settlement inscribed upon it. Enrique Lamadrid’s rich and extensive introductory essay constitutes a major part of this book providing a context for the 40 award winners featured in the final section. Hilos Culturales was a finalist in the Colorado Book Awards largely due to Lamadrid’s essay.

The book culminates with a catalogue of brief biographies along with photographs of the 40 recipients of Premio Hilos Culturales from 2000 to 2022. Premio Hilos Culturales awardees are deemed “living treasures who embody and preserve the continued vitality of this cultural tapestry.” These honored culture bearers preserve and perform traditions of the people of the Upper Río Grande del Norte.

As Lorenzo Trujillo, president of Hilos Culturales and a culture bearer honored in this book, said in a recent interview with Rocky Mountain Reader: “[This book] is a composite picture of who we are in the Southwest. Tradition is so much of who we are. Culture is a symbolic system that encodes the value of language, social structure and world view. This is our social structure – it’s the elders, you know. If our culture is valuable, it’s our responsibility as elders to preserve it”

The San Luis Valley is truly a cultural enclave geographically isolated and culturally separated from the rest of Colorado by mountain ranges, rivers and sand dunes. The image of the Valley that emerges from this book is that of a crucible where everything is put to a test – sustainable resources, access to water, agriculture, welfare of communities, and cultural survivals. The Upper Río Grande region skips over the state boundary between Colorado and New Mexico. Its geographic and sociocultural reach extends into New Mexico and south to Taos. Many current residents, like their ancestors, don’t recognize any official governmental demarcation that could impede the flow of life, relationships and culture from north to south and the reverse.

Enrique Lamadrid’s essay makes clear the cultural connectivity alive in this vast region but also links these connections to the history of the Iberian peninsula, to Spanish and Portuguese traditions, origins and influences. For example, the alabados (songs of praise), which are sung by the Penitente brothers during Lent, particularly, Semana Santa (Holy Week), in southern Colorado and northern New Mexico, recall Medieval plainchant as well as elements from Jewish and Muslim sacred music with bits of flamenco ornamentation added. Another example of colonial influences is La Entrega de Novios (delivery of the newlyweds and celebration of the formation of new families), the climax of the traditional wedding ceremony, which originated in 12th century Spain and is still staged today.

Listed in Lamadrid’s comprehensive cultural inventory of genres are corridos, ballads and narratives that portray historical figures, violence, oppression and Hispano cowboy culture, which are derived and adapted from European romances via Mexico. Lamadrid also discusses the Indo-Hispano legacy of different genres inspired by more local sources such as the indigenous populations of the Valley, Utes, Apaches and Comanches, popularized through festival performances, folklore and legends, plays (e.g., Los Comanches), songs and dances. Lamadrid pictures this rich influential mix as a tapestry when he writes: “… folklore and folkways of the Upper Río Grande del Norte cultural homeland have added threads, designs, and colors that reflect a tapestry that is constantly shifting and changing, weaving between languages, cultures, and traditions.”

In tracing and defining all these traditions, Lamadrid credits the tremendous efforts of Aurelio Macedonio Espinosa and his followers. He refers to Espinosa as “the cultural cartographer of Colorado.” This part of Lamadrid’s essay comprises a folklorist’s checklist such as Los Dichos [sayings], Los Juegos [games], Las Adivinanzas [riddles], Los Cuentos [folk stories], El Cancionero [songs] and Tradiciones Espirituales [religious culture]. The value of this catalogue not only lies in identification and commentary but it also demonstrates the hybridization of historical sources as they meld with contemporary artistic urges and creative demands.

Lorenzo Trujillo regards this book as “a milestone and a moment in history in the United States, in Colorado, in San Luis, because it, for the first time, is an official acknowledgement of our people as part of the mosaic [of Hispano culture] … that has been lost or ignored.”

Folklore is dynamic and always changing. This is the foundational message of this book as it honors a culture and culture bearers buoyed by inspiration from many sources, traditional to popular. The inventiveness of tradition and its companion, creativity, blend individuality with legacy. In light of this cultural dynamism, the contested notion of authenticity appears to reside “in the eye of the beholder.” Hispano performers demonstrate this repeatedly. Hilos Culturales: Cultural Threads of the San Luis Valley honors their dedication to tradition as well as their quest for innovation.

Resident of Rocky Mountains and the Pacific coast of New Zealand, Suzanne MacAulay is an art historian, folklorist and ethnographer. She is Professor Emerita and former chair of the Visual and Performing Arts Department, University of Colorado, Colorado Springs. Her research interests are arts revitalizations, ethnographic textiles, particularly Spanish Colonial colcha embroidery and Maori weaving. Her book, Stitching Rites, is the first comprehensive academic treatment of Spanish colonial colcha embroidery and Hispanic art revitalization movements. In 2019 she successfully nominated Josephine Lobato, folk artist from the San Luis Valley, Colorado, for a National Endowment for the Arts National Heritage Fellowship Award.

Click here for more from Suzanne Macaulay.