How to get to Bowfin Street

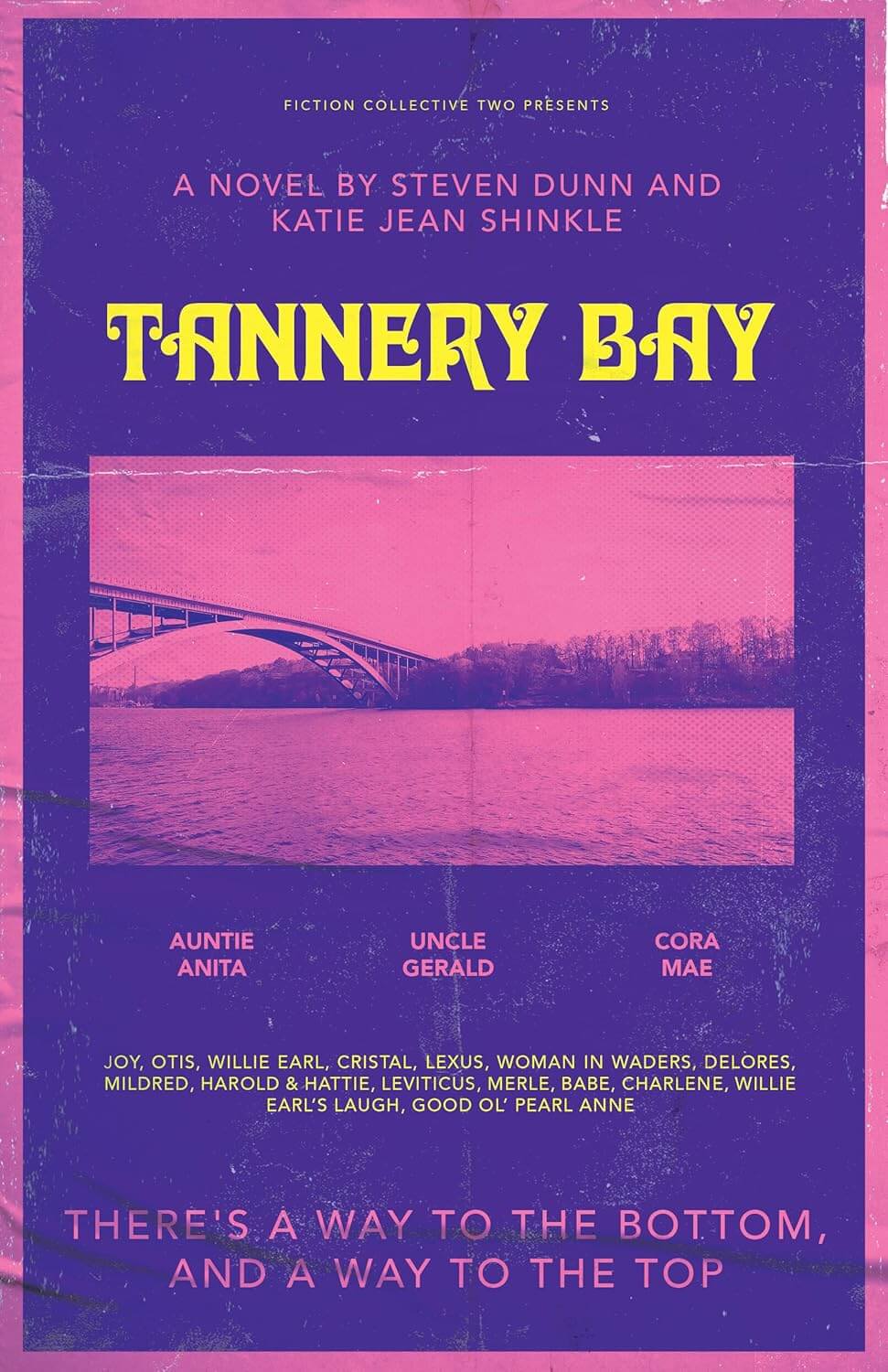

A fairy tale of a novel, Tannery Bay creates community magically

A fairy tale of a novel, Tannery Bay creates community magically

It is hot on Bowfin Street. The air is a lurid, Baker-Miller pink and the month is July, as it has been since anyone can remember. The residents of Bowfin return from their jobs with smiles for one another and gather for a family style dinner and after, a bit of scheming against those who keep them down.

Steven Dunn

Here is the enchanted settlement of Tannery Bay, an over-polluted seaside town where art comes to life, ghosts smile at you in the graveyard and laughs can dance the two-step. Populated by a tight-knit community of lovers, artists and workers, Tannery Bay is a would-be communal utopia—if it weren’t for the Owners, a greed-riddled class of oppressors who bend the town to their will.

Tannery Bay, co-written by Denver-based author Steven Dunn (Potted Meat, 2016; Water & Power, 2018) and Katie Jean Shinkle (None of This Is an Invitation, 2023), explores in its fantastical way the joys of the marginalized, the importance of community and family and the struggle to live under late capitalism.

Katie Jean Shinkle

In its aesthetics, Tannery Bay is a totally unique vision. A vivid sense of atmosphere permeates the novel throughout, especially in its visual construction. The saturation of pink in purple hues in the air, the goo-water of the bay, the stagnant heat of perpetual July and the neglected, run-down vibrancy of the novel’s locales form a fully realized world. One can smell the mildew of the Tannery Bay casino and the oxtail soup brewing in the cozy homes of Bowfin Street. Likewise, the reader suffocates under the gaudy opulence of the Owners’ Mcmansions and drowns in their unnerving fluorescence. Consistently and thoroughly, one senses the environment and is taken as in a dream by its thick and dusky moods.

Complimentary to its visuals is Tannery Bay’s tone: modern fairy tale. Each chapter opens with the well-worn “once upon a time,” and the narrative lines are peppered with whimsical and fantastical elements. The unofficial guide of the story is the “Woman in Waders,” a well-meaning ghost that appears at a distance and then ever closer as the plot of the story develops, offering the characters cockle shells and quiet direction. Auntie Anita, the matriarchal leader of Tannery Bay community, creates fantastical works of art featuring moving sculptures and animalistic magnolias delighting and inspiring melancholy reverie. In Tannery Bay, the possibilities are untamed, and the world is in harmony with its own magic. At their best, these elements prompt immersion into the novel, support the joyous vision of the character’s lives, and thicken the rich textual atmosphere.

Purchase at your local independent bookseller or at bookshop.org.

But for all its idiosyncrasies, something is lacking from Tannery Bay. The core plot of the novel is the characters’ struggle against the Owners, and yet it seems to occupy only a small place in the story. If removed, what the reader is left with is a ranging collection of moments and memories that deepen one’s understanding of the characters and the fullness of their lives, despite relentless oppression and the difficulties they face. The battle against the tyranny of the Owners reads almost as a side plot, and though it serves to give the story structure and resolution, it undercuts the parts of the novel most full of community, family and life.

This is tandem to what I find to be the most glaring flaw of the story: the lack of stakes. To compare our heroes and our villains: those that populate Bowfin Street are sensitive, creative, strong and ready to fight for their dignity, while the hideously caricatured Owners are rotting men driven only by greed and dominance, capable of violence to keep their place at the top. The righteous and the profane, respectively, a trope that lends itself well to the fairy tale form of Tannery Bay. And true to form, our heroes come out on top, but where exactly is the struggle for that victory? In fixing up a rundown city bus to use for art tours, a central action in the plot to ruin the Owners, the cast of characters plan for sweat and hard work to get the old bus running again. This, only to wake up one morning and find a brand new bus in place of the old, gifted to them by the magic of the town. Further, at every step of the plot, the Owners are comically and easily outwitted, offering no resistance to their comeuppance. One eventually begins to wonder how they became Owners in the first place. In the end, the reader is not even granted a confrontation between our heroes and villains as the Owners opt to kill themselves or each other, either outright or by their own stupidity, each death passing outside the awareness of the occupants of Bowfin Steet.

Yes, this story is a fairy tale and as such, it doesn’t need the gravity of tension that may be required of other novels. But the story is also a political one. At the core Tannery Bay is an exploration of environmental, racial and sexual injustice. There are points in the novel where this exploration comes to fruition, but ultimately it seems that an opportunity for didactics and clarity on the struggles of the marginalized has been neglected. Here, dignity and freedom are only some mild trickeries, some wit and a bit of magic away. Tannery Bay remains a fairy tale.

James McCurdy is a lifelong resident of the Rocky Mountains. Developing an interest in literature from an early age, McCurdy has continued to be engaged in the world of letters through his formal education, earning a dual BA in English Literature and Neuroscience. In his professional life, James has worked as a carpenter, a construction engineer and a grant writer. Through these diverse career choices, he has maintained a love of language and scholarship and is currently pursuing a Master's of English Literature at Freie Universität Berlin.

Click here for more from James McCurdy.